Mr Justice Dove :

Introduction

1. On the 31st October 2016 the Interested Party submitted a planning application to the Defendant, which the Defendant validated on the 2nd December 2016 for the redevelopment of a large urban site comprising, amongst other uses, the existing Elephant and Castle shopping centre and the London College of Communication. All of the existing buildings and structures contained within the site, which was subdivided for the purposes of some aspects of the consideration of the development into an east and a west site, are proposed to be replaced by way of redevelopment into a range of buildings up to 35 storeys tall, providing a mix of uses including 979 residential units and accommodation for retail office, education, assembly and leisure uses along with a remodelling of the London Underground station at Elephant and Castle. The Claimant is a resident within the Defendant’s administrative area and one of their tenants. He has lived in the Defendant’s administrative area all of his life and is a campaigner with a keen interest in housing issues who is a member of the “35% Campaign”, which is a group dedicated to ensuring the delivery of 35% genuinely affordable housing in new developments in areas such as that administered by the Defendant. As will appear below, the 35% Campaign made representations and objections in relation to the Interested Party’s development.

2. Planning permission was granted by the Defendant (subject to conditions and an obligation under section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990) on the 10th January 2019. As a consequence of the involvement of residential development within this large mixed-use scheme, provision was made in the light of policies which are set out below for the delivery of affordable housing. In essence the three grounds upon which this claim is brought are all related to criticisms of the affordable housing provision which was ultimately approved. This judgment sets out, firstly, the events leading up to the grant of planning permission and, so far as is necessary, events after the intimation of this claim and associated with this application for judicial review of the planning permission. Secondly, an overview of the three grounds of challenge is set out followed by, thirdly, the relevant legal principles. Finally, the judgment turns to an analysis of the arguments raised by the parties and conclusions in respect of the grounds upon which this application has been brought. Since the matter has been dealt with as a “rolled-up” hearing it is necessary to examine, firstly, whether or not permission ought to be granted for any of the three grounds and secondly, in the event that permission is granted, whether in substance the ground has been made out.

The facts

3. It is beyond argument that the proposed development in this case was a large and complex project, with a lengthy anticipated period for construction. In common with any planning proposal, alongside the many benefits which the proposed scheme is designed to bring, there are also potential detrimental social and environmental impacts which need to be brought into the decision-making equation. It is unnecessary for the purposes of this case to address questions associated with the wider planning merits of the Defendant’s decision and what follows necessarily focuses (as did the parties’ submissions) on the decision-taking process in respect of affordable housing.

4. Prior to embarking on a detailed history of the evolution of the affordable housing proposal in this case it is necessary to set out what is to be understood by affordable housing. Affordable housing is a portmanteau term which comprises a number of potential kinds of tenure. It is a term which is defined in annex 2, the Glossary, to the National Planning Policy Framework. For the purposes of the present case “affordable housing for rent” is defined as follows:

“(a) Affordable housing for rent:

meets all of the following conditions:

(a) the rent is set in accordance with the Government’s rent policy for Social Rent of Affordable Rent, or is at least 20% local market rents (including service charges where applicable);

(b) the landlord is a registered provider except where it is included as a Build to Rent Scheme (in which case the landlord need not be a registered provider);

And

(c) it includes provisions to remain at an affordable price for future eligible households, or for the subsidy to be recycled for alternative affordable housing provision. For Build to Rent schemes, affordable housing for rent is expected to be the normal form of affordable housing provisions and, in this context, is known as Affordable Private Rent.”

5. The Glossary goes on to define “Build to Rent” as follows:

“Build to Rent

Purpose built housing that is typically 100% rented out. It can form part of a wider multi-tenure development comprising either flats or houses, but should be on the same site and/or contiguous with the main development. Schemes will usually offer longer tenancy agreements of three years or more, and will typically be professionally managed stock in single ownership and management control.”

6. In addition, in London there are further definitions of affordable housing provided in the London Plan (March 2016). This provides as follows:

“POLICY 3.10 DEFINITION OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

Strategic and LDF preparation

Affordable housing is social rented, affordable rented and intermediate housing (see para 3.61), provided to eligible households whose needs are not met by the market. Eligibility is determined with regard to local incomes and local house prices. Affordable housing should include provisions to remain at an affordable price for future eligible households or for the subsidy to be recycled for alternative affordable housing provision

3.61 Within this overarching definition:

• social rented housing should meet the criteria outlined in Policy 3.10 and be owned by local authorities or private registered providers, for which guidelines target rents are determined through the national rent regime. It may also be owned by other persons and provided under equivalent rental arrangements to the above, as agreed with the local authority or with the Mayor.

• affordable rented housing should meet the criteria outlined in Policy 3.10 and be let by local authorities or private registered providers of social housing to households who are eligible for social rented housing. Affordable Rent is subject to rent controls that require a rent of no more than 80% of the local market rent (including service changes, where applicable). In practice, the rent required will vary for each scheme with levels set by agreement between developer providers and the Mayor through his housing investment function. In respect of individual schemes not funded by the Mayor, the London boroughs will take the lead in conjunction with relevant stakeholders, including the Mayor as appropriate, but in all cases particular regard should be had to the availability of resources, the need to maximise provision and the principles set out in policies 3.11 and 3.12.

• intermediate housing should meet the criteria outlined in Policy 3.10 and be homes available for sale or rent at a cost above social rent, but below market levels. These can include shared equity (shared ownership and equity loans), other low cost homes for sale and intermediate rent, but not affordable rent.

Households whose annual income is in the range £18,100 £66,000 should be eligible for new intermediate homes. For homes with more than two bedrooms, which are particularly suitable for families, the upper end of this eligibility range will be extended to £80,000. These figures will be updated annually in the London Plan Annual Monitoring Report.”

7. In 2017 Supplementary Planning Guidance was published by the Mayor of London entitled “Mayor of London’s Affordable Housing and Viability SPG 2017”. Of relevance to the present case is the inclusion within that document of a specific form of intermediate housing identified as “London Living Rent”. The SPG identifies that eligibility for London Living Rent is restricted to households renting with a maximum household income of £60,000 without sufficient current savings to purchase a home within the local area.

8. Against the backdrop of these definitions, for the purposes of the decision there were in addition various elements of the development plan and emerging development plan policies that were pertinent to the decision. Starting with the London Plan Policy 3.12 addressed the question of the provision of affordable housing as part of private residential and mixed-use schemes in the following terms:

“POLICY 3.12 NEGOTIATING AFFORDABLE HOUSING ON INDIVIDUAL PRIVATE RESIDENTIAL AND MIXED USE SCHEMES

Planning decisions and LDF preparation

A The maximum reasonable amount of affordable housing should be sought when negotiating on individual private residential and mixed use schemes, having regard to:

a) current and future requirements for affordable housing at local and regional levels identified in line with Policies 3.8 3.10 and 3.11 and having particular regard to the guidance provided by the Mayor through the London Housing Strategy, supplementary guidance and the London plan Annual Monitoring Report (see paragraph 3.68)

b) affordable housing targets adopted in line with Policy 3.11,

c) the need to encourage rather than restrain residential development (Policy 3.3),

d) the need to promote mixed and balanced communities (Policy 3.9),

e) the size and type of affordable housing needed in particular locations,

f) the specific circumstances of individual sites,

g) resources available to fund affordable housing, to maximise affordable housing output and the investment criteria set by the Mayor,

h) the priority to be accorded to provision of affordable family housing in policies 3.8 and 3.11.

B Negotiations on sites should take account of their individual circumstances including development viability, the availability of public subsidy, the implications of phased development including provisions for re-appraising the viability of schemes prior to implementation (‘contingent obligations’), and other scheme requirements.” (emphasis added)

9. In addition to this London-wide policy the Defendant had its own part of the development plan, the Core Strategy (2011) and, in particular, Strategic Policy 6 which provided as follows:

“Strategic Policy 6 – Homes for people on different Incomes

…

Our approach is

Development will provide homes including social rented, intermediate and private for people on a wide range of incomes. Development should provide as much affordable housing as is reasonably possible whilst also meeting the needs for other types of development and encouraging mixed communities.

We will do this by

1. Requiring as much affordable housing on developments of 10 or more units as is financially viable.”

10. The explanatory text for this planning policy cross-refers to saved policy 4.4 of the earlier Southwark Plan, which sets out a minimum requirement of 35% affordable housing on the basis of a split of 50% social rented and 50% intermediate housing. The site falls within the Elephant and Castle Opportunity Area for planning policy purposes. The detailed provisions of policy 4.4 are as follows, so far as relevant to these proceedings:

“Policy 4.4 - Affordable Housing

The LPA will endeavour to secure 50% of all new dwellings provided in Southwark as affordable in accordance with the London Plan. As part of private development, the LPA will seek to secure the following provision of affordable housing:

i. Within the Urban and Suburban Density Zones and within the Elephant and Castle Opportunity Area, at least 35% of all new housing as affordable housing, for all developments capable of providing 15 or more additional dwelling units or on sites larger

than 0.5 hectare, except in accordance with Policy 4.5

…

vi. A tenure mix of 70:30 social rented: intermediate housing ratio except as stated below for opportunity and local policy areas

…

|

Area Designation |

Social Rented (%) |

Intermediate (%) |

|

Elephant and castle Opportunity Area |

50 |

50 |

” (emphasis added)

11. At the time of the decision-taking process in relation to this case there was an emerging Southwark Plan which also contained policies in relation to new housing including a policy for private rented housing schemes which provided as follows:

“P4: Private rented homes

New self-contained, private rented homes in developments providing more than 100 homes must:

1.1 Provide security and professional management for the homes; and

1.2 Provide a mix of housing sizes, reflecting local need for rented property are provided; and

1.3 Provide the same design standards required for build-for-sale homes; and

1.4 Provide tenancies for private renters for a minimum of three years with a six month break clause in the tenant’s favour and structured and limited in-tenancy rent increases agreed in advance; and

1.5 Meet Southwark’s Private Rent Standard; and

1.6 Be secured for the rental market for a minimum 30 year term. Where any private rented homes are

sold from the private rented sector within 30 years this will trigger a clawback mechanism resulting

in a penalty charge towards affordable housing; and

1.7 Provide affordable homes in accordance with P1 or Table 3, subject to viability. Where the provision of private rented homes generates a higher development value than if the homes were built for sale, the minimum affordable housing requirement will increase to the point where there is no financial benefit to providing private rented homes over built for sale homes.

1.8 Be subject to a viability review to increase the number of and/or the affordability of affordable homes where an improvement in scheme viability is demonstrated between the grant of planning permission and the time of the review.

2 Discount market rent homes at social rent equivalent must be allocated to households on Southwark’s social housing waiting list. All other discounted market rent homes must be allocated

to households on Southwark’s Intermediate Housing List.

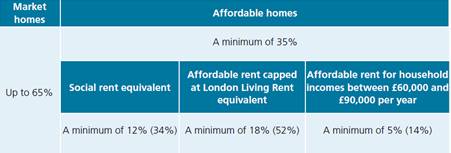

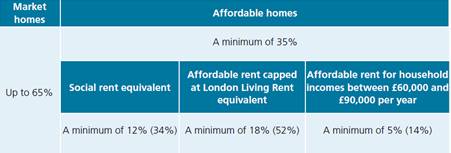

Table 3: Affordable housing requirement option on qualifying private rented homes scheme

Affordable homes

12. Against the backdrop of this raft of policy the Interested Party formulated an offer in relation to affordable housing. When the matter was first reported to the Defendant’s planning committee on the 16th January 2018 the officers recorded that the Interested Party’s proposal was to provide 36% affordable housing based upon habitable rooms, and amounting to some 342 units out of the 979 residential units within the scheme. The affordable housing was to be provided in the form of discount market rent housing to be provided in perpetuity. The officers noted that, at 36%, this exceeded the minimum requirement of 35%. However, the proposed tenure split did not satisfy the policy requirement from policy SP6 of the Core Strategy, as no traditional social rented accommodation formed part of the proposal. Additionally, it was noted that the distribution of rental levels did not conform either to emerging policy P4 or the London Living Rent level. Notwithstanding these shortcomings, officers went on to report that the viability of the scheme had been independently evaluated by the Defendant’s valuation consultants, and on the basis of an internal rate of return (“IRR”) of 7.15%, together with annual growth to 11% over the construction period, that the affordable housing offer “represents the maximum reasonable affordable housing provision” taking account both of the review mechanism proposed in respect of the provision of affordable housing and the need to provide appropriate flexibility to ensure the deliverability of the scheme as a whole.

13. The minutes of the meeting of the 16th January 2018 record that a motion to grant planning permission was moved but defeated. A motion to refuse the application was proposed at the meeting, but ultimately the decision on that motion was deferred to a future meeting. That meeting occurred on the 30th January 2018, and it appears from a supplemental report that was provided to that meeting that part of the purpose of deferring the consideration of the application was to enable officers to prepare putative reasons for refusal based on members’ discussion at the earlier meeting. The supplemental report provided a schedule of potential reasons for refusal including one associated with the Interested Party’s proposals for affordable housing. The minutes of the meeting of the 30th January record that on the afternoon prior to the meeting the Interested Party had made further proposals in relation to affordable housing (amongst other matters), and members resolved to defer the item to a future meeting.

14. On the 5th February 2018 the Interested Party’s planning consultant wrote to the Defendant’s officers setting out a revised and updated affordable housing offer. The letter sets out the offer presented to the planning committee on the 16th January and the amended and updated offer in the following terms:

“The affordable housing offer presented to Planning Committee on 16th January is set out below in Table 1:

Table 1 – Agreed Affordable Housing Offer

|

Social Rent

Equivalent |

London Living Rent (household incomes up to £60k) |

DMR | |

| |

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

Total |

|

West |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1b MR |

3 |

5 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

15 | |

34 |

|

2b MR |

13 |

20 |

25 |

13 |

8 |

20 |

32 |

128 |

|

3b MR |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

5 |

|

East |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

1b MR |

6 |

21 |

10 |

6 |

20 | | |

63 |

|

2b MR |

8 |

15 |

15 |

8 |

2 |

13 |

23 |

84 |

|

3b MR |

2 |

4 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

22 |

| | | | | | | | |

|

Total unit mix |

33 |

63 |

62 |

33 |

34 |

52 |

59 |

336 |

|

Unit % |

10% |

19% |

18% |

10% |

10% |

15% |

18% |

100% |

|

Hab room % |

10% |

17% |

19% |

10% |

8% |

15% |

20% |

100% |

The Council confirmed that the above mentioned affordable housing offer, was deemed to be “maximum reasonable” in planning policy terms and represented an offer that Officers had deemed to be acceptable.

Updated Affordable Housing Offer

The Agreed Affordable Housing Offer has been reviewed and Table Two below represents the Updated Affordable Housing Offer.

Table 2 – Updated Affordable Housing Offer

|

Social Rent |

London Living Rent (household incomes up to £60k) |

DMR | |

| |

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

Total |

|

West | | | | | | | | |

|

1b MR |

12 |

2 |

10 |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

34 |

|

2b MR |

41 |

10 |

25 |

- |

- |

- |

27 |

103 |

|

3b MR |

21 |

- |

7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

28 |

|

East |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

1b MR |

- |

9 |

9 |

- |

- | |

35 |

53 |

|

2b MR |

- |

12 |

11 |

- |

- |

- |

89 |

112 |

|

3b MR |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| | | | | | | | |

|

Total unit mix |

74 |

33 |

62 |

- |

- |

- |

161 |

330 |

|

Unit % |

22.4% |

10.0% |

18.8% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

48.8% |

100% |

|

Hab room % |

24.9% |

9.4% |

18.5% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

47.2% |

100% |

The key components of the Updated Affordable Housing Offer are:

· The provision of 35% affordable housing calculated by habitable room, in accordance with the Council’s existing and emerging policy requirement and the GLA’s Threshold requirement for Build to Rent schemes;

The provision of 74 social rented units to be located on Plots W1 & W2 on the western part of the West Site. This replaces the 33 social rent equivalent units included in the Agreed Affordable Housing Offer. The 74 social rented units will be owned and operated by either LB Southwark or a Registered Provider.”

In essence, the material changes for present purposes were that the units of social rent equivalent in the original offer had been replaced by units of social rent, and the number of units in each of these categories had been increased from 33 in the original offer to 74 in the updated offer.

15. On the 15th June 2018 the Interested Party’s planning consultants again wrote to the Defendant’s officers in respect of the proposals for affordable housing. In that letter they provided a further and improved offer in respect of the affordable housing component of the proposals. The correspondence described the revised proposal as follows:

“We wrote to you on 13th February 2018 setting out proposed revisions to the submitted scheme which were subsequently consulted on formally by the Council. Those revisions included improvements to the affordable housing offer through the introduction of 74 Social Rent homes on the West Site (Plot W3 Buildings 1 and 2, fronting Oswin Street).

Discussions with the Greater London Authority (“GLA”) have progressed positively since February 2018, and we are pleased to confirm an in-principle agreement from the GLA to provide grant funding towards the proposed scheme. As evidenced by the enclosed GLA letter dated 14th June 2018 (Appendix 1), the Applicant’s affiliated company, T3 Residential Limited, is eligible to become an Investment Partner and eligible to apply for grant funding from the Mayor’s Affordable Homes Programme, a bid for which has been welcomed and will follow in due course.

The grant funding enables the delivery of a further 42 Social Rent homes on the West Site (Plot W3 Building 3) which means 116 Social Rent homes are now proposed in total. It is envisaged that these will be owned and managed by Southwark Council. Overall, the scheme will continue to deliver 35% affordable housing (calculated by habitable room). Appendix 2 contains a Table summarising the Further Updated Affordable Housing Offer at 15th June 2018. For the avoidance of doubt, the Applicant is now able to commit unconditionally to this affordable housing offer.”

The offer was further set out in a table as follows:

“Appendix 2

|

FURTHER UPDATED AFFORDABLE HOUSING OFFER - 15 JUNE 2018 |

|

|

Social

Rent |

London Living

Rent (household

incomes up to £60k) |

DMR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

G |

Total |

|

West |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1b |

22 |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

10 |

34 |

|

2b |

66 |

10 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

27 |

103 |

|

3b |

28 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

28 |

|

East |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

1b |

- |

9 |

9 |

- |

- |

|

35 |

53 |

|

2b |

- |

12 |

11 |

- |

- |

- |

89 |

112 |

|

3b- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total unit mix |

116 |

33 |

20 |

- |

- |

- |

161 |

330 |

|

Unit % |

35.1% |

10.0% |

6.1% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

48.8% |

100.0% |

|

Hab room % |

38.1% |

9.4% |

5.3% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

47.2% |

100.0% |

”

A further explanation of the change in the proposal was set out by the Interested Party’s planning consultants in a response to the schedule addressing members’ putative reasons for refusal:

“This means the number of social rented homes increases from 33 to 116, assisted by securing grant funding from the GLA. The intention has been to provide larger family units for the Social Rented homes. The Social Rented homes will now be owned and managed by Southwark Council or a Registered Provider.

In order to be able to viably accommodate the increase in social rented homes the number of London Living Rent homes reduces from 158 to 53, and the number of Discounted Market Rent (DMR) homes increases from 145 to 161.”

16. The reference to grant support in relation to the provision of affordable housing related to a letter from the GLA dated 14th June 2018 which provided as follows:

“Following an initial review however, I can confirm that T3 Residential Limited would be eligible to become an Investment Partner once the more detailed assessment has been carried out and any clarifications addressed. As an Investment Partner with the GLA T3 Residential Limited would be eligible to apply for grant funding for the Mayor’s Affordable Homes Programme.

Subject to successful registration of T3 Residential Limited with the Regulator of Social Housing and the full assessment of your IPQ application, the GLA would welcome a bid for grand funding from the Mayor’s Affordable Homes Programme to support the development of 330 affordable housing dwellings at Elephant and Castle; planning application no. 16/AP/4458, being 116 social rent dwellings at a grant rate of £60,000 per dwelling and the remaining 214 affordable homes at a grant of £20,000 per dwelling.”

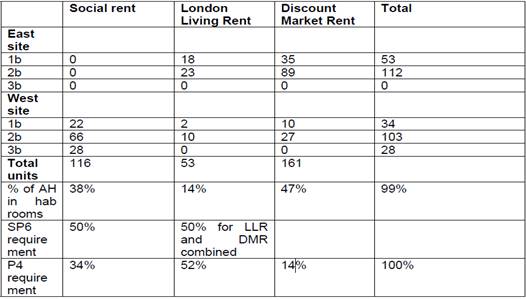

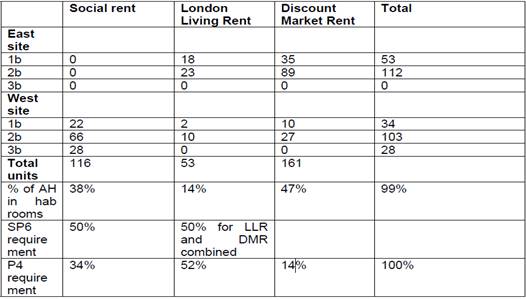

17. The Interested Party’s application returned to committee on the 3rd July 2018 and the planning committee were assisted by a revised and updated officers’ report for the purposes of their discussion. The officers set out the affordable housing proposals together with their evaluation of them against policy as follows:

“360. Alongside a new shopping centre, a new education campus and other uses the redevelopment of the shopping centre and LCC site proposes a number of residential towers and blocks which provide a total of 979 residential units. The development as proposed would be primarily PRS (Private rented sector) also known as a Build to Rent product but with traditional social rented units provided on the west site as opposed to the previous offer which was for social rent equivalent units as envisaged in draft policy P4. The table below sets out the applicant’s proposed affordable housing offer, set out against the requirements of the current adopted policy in the Core Strategy and those of the emerging policy in the draft NSP. The proposal is for 35% affordable housing based on habitable rooms.

Overall affordable housing offer (east and west sites combined)

361.

362.

363.

363. Whilst the proposal would comply with the policy requirement to provide a minimum of 35% affordable housing by habitable room, the above demonstrates that it would not comply with the adopted core strategy policy which requires the affordable housing to be a 50/50 split between social rented and intermediate units. It would also not comply with emerging policy P4 because, whilst the social rented units would just exceed the minimum requirement, there would be too much Discount Market Rent and too little London Living Rent.

364. The affordable housing proposed would also not be evenly distributed across both sites, with the social rented units all being delivered on the west site. The s106 agreement would therefore stipulate that if the development on the west site has not substantially commenced within 10 years of the east site commencing, the land and sum of money sufficient for construction and completion of the social rented units would be transferred to the council, to deliver the social rented units.

Fall-back position

365. The applicant also wishes to retain a fall-back position whereby the west site could be delivered as traditional build-to-sell units. The exception to this would be the social rented units in the mansion blocks which would be delivered in any event. The developer would notify the council, of the intention to develop the west site as build to sell, and the affordable housing requirement for this would be for 50% social rented and 50% intermediate. Some of the west site’s social rented units would already be secured in the mansion blocks, albeit 38% rather than the 50% requirement, therefore a review mechanism would be required.

…

370. The proposal as amended meets the policy requirement of 35%.

371. In contrast to the original submission the revised proposal includes the provision of traditional Social Rented housing – 116 units which would be located on the west site within 3 Mansion blocks. This amounts to 38 % of the affordable which set against

policy SP6 is below the required 50%. In relation to the east site the rental levels do not conform to the distribution requirement set out in emerging policy P4. The proposal reflects GLA grant funding, recently confirmed, which has facilitated an increase in the number of social rented units from 74 to 116.

…

380. Within the Elephant and Castle Opportunity Area the policy requirement as set out in Core Strategy SP6 is for a tenure split of 50:50 between social rented and intermediate. The rental distribution set out above does not accord with this stipulation.

381. As a DMR product it is possible to compare the proposed tenure in terms of rent levels but the tenancies are not comparable as many of the terms vary. The tenancies are based on three year leases which can be renewed. These are assured shorthold tenancies but with more favourable terms than the minimum requirement where there is no right to renew or requirement for a lease longer than 12 months.

382. The social rent units now proposed on the west site within the mansion blocks would have standard SR tenancies as the units would be managed by either the council or an RSL.

383. Although the DMR units would be comparable to other affordable units in terms of rent levels the nature of the tenancies is somewhat different. All the DMR tenancies will be based on 3 year leases which can be renewed and with a tenant only break. One other key distinction proposed is that eligibility based on income would be reviewed on renewal of leases (other than for the social rented equivalent units). Whilst this is different to tenancy terms with affordable housing providers it does provide the benefit of ensuring more turnover and availability within this tenure. It will also assist the application of any clawback to increase number of units in the lower rental bands (see below).

384. The rents themselves would be inclusive of service charges. Indicative typical rents for the scheme have been identified as follows:

385. Acknowledging the limited weight to be applied to emerging policy P4 and in the absence of an adopted policy (in the Core Strategy) that addresses PRS and DMR as a means of Housing and Affordable housing provision, nonetheless it is worth considering the proposal against these emerging tenure split requirements. As drafted, in relation to affordable provision requirements of a minimum 35%, the policy seeks a breakdown of 34% Social rent equivalent; 52% London Living Rent equivalent and 14% GLA income levels.

386. The application as revised now proposes 52.8% of the affordable habitable rooms to be at rents consistent with or below the LLR. The majority of that accommodation would be at social rent levels.

387. Hence overall the breakdown of the affordable component would be:

38% social rent

14% LLR and

48% at 80% market rent for household incomes between £80,000 - £90,000 (reflecting the upper limit of the Mayor’s income threshold for intermediate housing.)

388. This fails to meet the requirements of the emerging policy tenure split requirements. The applicant has sought to ensure that a minimum of 35% policy compliant affordable is provided but for viability reasons it is submitted that the tenure split as proposed by emerging policy P4 cannot be met. The applicant states that adhering to the proposed P4 tenure split would result in a reduction in the overall quantum of affordable housing based on viability.

389. The above analysis therefore indicates that, subject to consideration of viability, there would be a material conflict with the development plan in respect of the form and mix of the affordable housing offer. However, it is of note that the main improvement that arises from the revised proposal is the provision of social rented accommodation to be operated by the council or a RSL. The tenure split breakdown is also out of step with the expectations in the emerging policy.”

18. The committee report then turned to consider in the light of these conclusions the question of development viability. As set out above, the Defendant had engaged its own independent consultants to assist with the valuation exercise. The advice which the consultants had provided together with the conclusions in relation to viability were set out in the committee report as follows:

“393. The council’s valuation experts have advised that the applicant’s offer of 36% affordable housing (DMR) could be achieved with a fully compliant tenure mix but predicated upon an initial IRR of 6.50%, which, through rental growth and cost management over the construction period, would be in the order of 10 to 12 % upon practical completion.

394. The applicant’s approach is to base the offer on an initial IRR of 7.15% (applicant’s view of current rate vs 6.5% advised above ) which will allow for 36% affordable housing but with a tenure mix that has just 50% in the lowest 4 income bands. To increase this affordability to 86% in these income bands, in accordance with emerging policy P4, the IRR would need to increase over time to 10 -12%. The applicant’s position is for this predicted uplift to be secured by a clawback review mechanism in the S106 agreement. Such a review mechanism would need to be both sophisticated and robust to maximise the level of affordable units, in the lower rental bands, that is both reasonable and viable.

395. The Applicant has conceded that 7.15% initial IRR plus annual growth to 11.00% over the construction period is acceptable. All current forecasts suggest that this growth in IRR over the construction period is achievable and possibly conservative. Based upon current market data the advice is that there appears to be no reason why this approach could not deliver a fully compliant scheme. This is based on predicted growth rates and because it is predicted rather than actual the applicant therefore wishes to rely on the review mechanism due to the risk involved where the affordable housing would be based on a predicted IRR.

396. The essential difference concerns the burden of risk. A policy compliant scheme is not viable at an IRR of 6.50 - 7.00 % whereas it is at 11.00 %.

397. It is clear that the development plan expectations for affordable housing need to take account of viability. The maximum reasonable amount of affordable housing is assessed taking account of viability.

398. Officers are satisfied in the light of the viability testing outlined above that the Applicant’s affordable housing offer (coupled with the securing of an appropriate review mechanism – see below) represents the maximum reasonable affordable housing provision taking account of the need for the council to apply its affordable housing requirements with some appropriate flexibility in accordance with the Mayor’s emphasis in the London Plan to ensure that the scheme as a whole is deliverable. In respect of the revised offer, the council’s experts are reviewing the increased social rented provision and the reconfiguration of rents. Officers are seeking their confirmation that it produces the same outturn as the previous mix and whether they remain of the view that it also represents the maximum reasonable quantum of affordable housing.”

19. The final element of the assessment of affordable housing related to the advice to members in relation to the need for a viability review given the scale of the project and the length of time over which it was likely to be being delivered. The advice contained in the committee report provided as follows:

“402. In view of the fact that the affordable housing provides a compliant quantum of 35% but has a non-compliant tenure split, and in line with the council’s Development Viability SPD, a viability review (VR) would be required. This is to ensure that if the economic circumstances of the scheme change in the future an improved tenure split can be achieved in order to be more closely if not fully compliant with policy. The detailed requirements for the viability reviews will be secured within the S106 legal agreement.

403. As with any development of this nature a viability review will be triggered in the event that development has not substantially commenced within 36 months of the grant of planning permission. This is 12 months longer than the norm to allow for the extended clearance and preparatory works that a scheme of this scale entails. In these circumstances 36 months is considered to be justified. There will be a post implementation review for each site to be undertaken at 75% occupancy. Any uplift, at 50% to the council, would be applied to adjust rental levels downwards towards meeting the distribution set out in emerging policy P4.

404. In the event that the West site is delivered as open market for sale the review will need to take into account the policy requirement for a different tenure split of 50:50 social rented and intermediate. In addition it should be noted that regardless of whether the west site comes forward as build for sale, or if for any reason the development stalled and ultimately failed to proceed, the applicant has confirmed that the social rented units will be delivered. This will be secured with the legal agreement.

405. The council’s Development Viability SPD suggests that the apportionment of any uplift would be based on a 50:50 split. Any uplift above the agreed IRR of 11% as set out in the final FVA would be applied to increase the percentage of affordable units at the social rent equivalent and London Living rent equivalent units with the aim of getting closer to a policy compliant level.”

20. The ultimate conclusion in relation to affordable housing advised by the officers was as follows:

“Conclusion of affordable housing

415. The proposal is for a new form of affordable housing which has not previously been provided in Southwark. However it is a form of affordable provision which is being recognised as making a useful contribution to addressing housing need. Notwithstanding the extent to which the affordable housing provision is contrary to some elements of the development plan notably the Core Strategy, officers are satisfied that the provision, as revised, is the maximum reasonable and that it is in overall conformity with the development plan taking account of scheme viability.”

21. The officers’ report advised members of the objections which had been received to the development as a result of consultation. Those representations included objections from the 35% Campaign, which were focused upon the contention that the affordable housing provision which was on offer was not policy compliant and was inadequate. These objections related to both the earlier offer in respect of affordable housing and also that which was presented to members following its upward revision. The officers prepared two addendum reports to update the officers’ report for members’ consideration. Addendum no.1 report contained the following elements of additional information and corrections to the original officers’ report:

“10. Additional information to supplement paragraphs 348-415 of the officer report

11. Viability review of applicant’s revised offer – GVA which is advising the Council on the viability of the proposed development has confirmed that the applicant’s revised affordable housing offer, which includes an agreement in principle for grant funding from the GLA, is the maximum that the development can reasonably support. GVA has also confirmed that the provision of grant funding would not increase the developer’s profit in comparison with the earlier affordable housing offer which included 74 social rented units.

12. Corrections to paragraphs 393, 394 and 412 of the officer report:

The proposed affordable housing would equate to 35% by habitable room, not 36% as stated in the report.

…

16. Viability of a build-to-sell scheme on the west site – The applicant’s revised affordable offer includes a fall-back position where the units on the west site could be developed as build-to-sell. Viability information has been submitted to appraise this option, which has been reviewed by GVA on behalf of the Council. GVA have advised that at the present day this build to rent would be less viable than the proposed build-to-sell scheme, and a review mechanism would be required in order to capture any uplift in value. It is noted however, that the applicant’s intention is to develop both sites as build-to-rent.”

It was common ground at the hearing that the build-to-sell referred to in the third sentence of paragraph 16 was a reference to a build to rent proposal. The addendum no. 1 report also recorded further objections from the 35% Campaign, and in particular the 35% Campaign’s request for confirmation that the latest affordable housing made by the Interested Party would be delivered even if grant funding could not be secured to support it. The response from the officers to that request was set as follows:

“23. Officer response – these comments are largely considered within the affordable housing section of the report a paragraphs 348-415 (pages 92 to 101). There is an agreement in principle for grant funding from the GLA of £11.24m towards affordable housing. The applicant has committed to providing the level of affordable housing set out in the latest offer, and including 116 social rented units, and this would be secured in the s106 agreement. If the social rented units were owned and managed by a Registered Provider they would offer secure tenancies, which would be secured through the s106 agreement.

24. The phasing of the proposed development across two sites and with all of the social rented units being delivered on the west site means that not all tenures of housing could come forward at the same time. The s106 agreement would prevent occupation of a proportion of the market housing until and unless the affordable units were completed, and this is routinely incorporated into legal agreements.”

22. The addendum no. 2 report referred the committee to additional objections from the 35% Campaign. These included the objection that the committee could not reach a reasonable decision on the application if the Interested Party was not prepared to commit to one or other of build to rent or build to sell on the west site, as the affordable housing requirements would be different in respect of those alternative proposals. The officer’s response to this contention in the addendum no. 2 report was as follows:

“14. …Addendum Report 1 considers viability for a build-to-sell scenario on the west site which would be fall back position in any event, and the social rented units would be protected. The applicant’s proposal and clear intention is to develop the west site for PRS but has indicated a possible if unlikely scenario whereby it would be developed for sale. This would trigger a slightly different affordable housing requirement. The S106 legal agreement will set out how this would be addressed should it arise and ensure that the requisite affordable housing provision would be secured. The committee is entitled to consider the application on that basis.”

23. Following debate the members of the planning committee resolved to grant planning permission. The specific terms of the resolution so far as relevant to the present case was as follows:

“RESOLVED:

1. That planning permission be granted, subject to conditions and the applicant entering into an appropriate legal agreement, and subject to referral to the Mayor of London, notifying the Secretary of State, and subject to a decision from Historic England not to list the shopping centre.

…

4. In the event that the requirements of (a) are not met by 18 December 2018, that the Director of Planning be authorised to refuse planning permission, if appropriate, for the reasons set out at paragraph 757 of the report.

5. That ward councillors would be consulted on a developed draft of the section 106 agreement.”

24. It appears that on the 9th July 2018 a member of the London Assembly wrote to the GLA enquiring as to the status of the grant funding of the affordable housing in the scheme and in particular the letter of the 14th June 2018 from the GLA set out above. In response the Executive Director for Housing and Land at the GLA replied as follows:

“The correspondence from my team to T3 Residential Limited dated 14h June 2018 was issued in response to its application for Investment Partner status with the GLA. All housing providers wishing to access grant to deliver affordable housing in London are required to complete this process.

The letter from my team does not constitute a funding agreement nor does it commit the GLA to make grant funding available in future. The purpose of the letter was to confirm receipt of T3 Residential’s application to become a GLA Investment Partner and outline details of the conditions under which grant funding may be available to T3 Residential to support delivery of affordable housing at Elephant and Castle.”

25. Following the passing of the resolution to grant planning permission, discussions and negotiations proceeded in relation to the obligation under section 106 of the 1990 Act which needed to be entered into to justify the grant of permission in accordance with the resolution. It appears that a draft was in relatively settled form by the 10th October 2018 and, in accordance with the resolution, it was circulated for consultation to the relevant ward councillors. For present purposes it is necessary to focus on the negotiations and agreements which were reached in respect of the affordable housing provisions, and in particular giving effect to paragraphs 364, 365 and 401 of the officer’s Report which addressed the issue of ensuring that the affordable housing was provided in the absence of commencement of its construction by the Interested Party. The drafting of the section 106 agreement also had to engage with the fall back position in the event of the Interested Party deciding to opt for a build to sell solution for the development of the west site.

26. Having circulated an initial draft of the section 106 obligation to ward councillors around the 10th October 2018, on the 1st November 2018 the Defendant’s officer Ms Hussain followed up a meeting with an email to the Interested Party’s solicitors setting out the position of the Defendant in the following terms:

“Following Monday’s meeting the Council reviewed the Planning Committee Report and addendum from the 3rd July in order to ascertain what the s106 agreement can and should secure. The following matters in respect of the Social Rented Units and the LUL issue can therefore be the Council’s only position on the matter and any departure from this position will require the matter to go back to the Planning Committee for fresh consideration.

West Site Social Rented Units

1. The Council has to secure delivery of the Social Rented Units on the West Site in order to give effect to Planning Committee’s resolution to grant. In negotiating the s.106 agreement it has become apparent that the Council will need to have the relevant West Site land transferred to it in circumstances other than if the West Site is not substantially commenced within 10 years of the East Site substantially commencing. The Council believes that transfer of the land is required in 3 additional scenarios and I list all 4 scenarios below for completeness;-

i) the West Site is not substantially commenced within 10 years of the East Site substantially commencing; (para 364)

ii) the West Site is sold at arms length to a third party entity not related or connected to the Developer or as part of any corporate restructuring (and excluding the sale of the West Site to the Developer by UAL) (para 365) or

iii) the West Site is implemented and construction of the core of the Social Rented Units has completed but development then stalls for a continuous period of 6 months (paras 365, 404); or

iv) the West Site is delivered as Open Market Build for Sale (paras 365, 404)

2. Failure to secure transfer of the Social Rented Units in the above scenarios would put the Council in breach of paragraphs 364, 365 and 404 of the officer’s report and would therefore require the Council to refer the matter back to the Planning Committee, or failing that, would run the risk of a potential judicial review challenge. The Council therefore requires your client to accept an obligation to transfer the land to the Council together with the construction and demolition costs in the above four scenarios. Drafting has been inserted into the s106 agreement to deal with the non-residential units which form part of the same block which hold the Social Rented Units.”

27. A draft of the section 106 agreement with obligations contained within it which reflected this email was distributed at the same time. On the 15th November 2018 the drafting of the section 106 obligation moved further forward. In the clauses addressing the delivery of the affordable housing on the west site in the event that the Interested Party had not commenced it within agreed timescales, a concept of “net SR Construction Costs” was introduced. This concept was to represent the difference between the cost of delivering the social rented units and the value of those units, and was a sum designed to be paid to the Defendant in order to enable it to complete the social rented units.

28. On the 20th November 2018 there was a further exchange of emails between Ms Hussain on behalf of the Defendant and the Interested Party’s solicitors in respect of a number of issues associated with the section 106 obligation, which included the question of mechanisms to ensure the delivery of the social rented units on the west site. The approach taken in the version of the section 106 in draft at that time provided that in the event of a failure to construct the core of the social rented units within ten years of substantially commencing development of the east site, or in the event of a continuous period of inactivity of the west site for more than six consecutive months, the Defendant would then be entitled to trigger mechanisms set out in the obligations to ensure delivery of the affordable housing. The detail of the obligation in this regard was the subject matter, amongst other issues, of the email exchange. In the quote set out below Ms Hussain’s email is in normal type and the response of the Interested Party’s solicitors is set out in capitals. The email of the 20th November 2018 records the exchange as follows:

“7. The Council needs sole discretion regarding the Social Rented Unit transfer options as we can’t have an option imposed on us. Your client would have had 10 years from grant of planning permission to decide if it wants to deliver the units, but in the event that the scenarios are triggered then the Council is able to dictate. NOT ACCEPTABLE ALTHOUGH WE APPRECIATE THE POINT OF THE COUNCIL NOT BEING OBLIGED TO BUILD. SUGGESTION IS FOR THERE TO BE TWO OPTIONS- EITHER TRANSFER THE LAND WITH NIL PAYMENT AND THAT WAY THE TIMESCALES TO BUILD ARE REMOVED OR WE BUILD THE SOCIAL RENTED AT THAT POINT- IN EFFECT THE DOWRY PAYMENT FALLS AWAY. IT MUST BE DEVELOPERS CHOICE TO WHICH OPTION IS PURSUED.

The Council can not accept an agreement which fails to secure an option where the construction costs will be paid by the Developer. To do so would be contrary to paragraph 364.”

29. This email exchange was reflected in further revised drafting sent from the Defendant to the Interested Party on the 22nd November 2018. There were then further discussions and a further draft emerged on the 27th November 2018. There was by now a relatively settled position as to the triggers entitling the Defendant to call for the implementation of the obligation to complete the social rented units. As set out above, the triggers were that either the social rented units had not been substantially commenced within ten years following the development being implemented on the east site, or that following substantial commencement of development on the west site there had been a continuous period of inactivity on the west site for more than six consecutive months. In circumstances where either of those events arose, it was agreed that the Defendant could notify the Interested Party that the trigger had occurred, following which the obligation provided for the Defendant and the Interested Party to agree upon which of three options should apply to ensure delivery of the social rented units, with option 2 as the option in default of agreement. Option 1 involved the grant by the Interested Party to the Defendant or a registered provider of a long leasehold interest along with the net SR Construction Costs; option 2 was the grant by the Interested Party to the Defendant or a registered provider of a long leasehold interest to enable them to construct social rented units together with the payment by the Defendant of the net SR Construction Costs in the amount of £1 only, in recognition of the fact that the Defendant or registered provider would have the benefit of significant development value arising not only from the social rented units, but also the non-residential floor space which was incorporated as part of this mixed use block of development; finally, option 3 was the Interested Party electing to undertake the construction of the social rented unit itself. The introduction of the dowry payment of £1 in option 2 was expressly incorporated, in accordance with an email from Ms Hussain dated the 27th November 2018, to reflect her view that “a fall-back position with no dowry payment might be perceived as a conflict with paragraph 364 of the PC Report”. It was therefore on that basis that the dowry payment of £1 was included. On the 29th November the draft section 106 obligation was sent to ward councillors amongst others, and uploaded onto the council’s planning register. The draft circulated was in effect the final version which was executed in order to enable planning permission to be granted.

30. On the 10th January 2019 the section 106 obligation was executed and planning permission was granted. The section 106 obligation is a lengthy document covering a wide variety of types of obligation. For present purposes it is necessary to focus solely on those relating to affordable housing, and in particular affordable housing delivered as part of the west site. Starting with clause 1, the following operational definitions are relevant to the arguments raised by the parties in the present case:

“1. Definitions and Interpretation

The following words and phrases shall have the following meanings unless the context otherwise requires:

“Affordable Housing Cap” means 35 per cent of Habitable Room of the Residential Units within the Development with a tenure split of:

means 35 per cent by Habitable Room of the Residential Units within the Development with a tenure split of:

(i) 38 per cent Social Rented Habitable Rooms, 48 per cent London Living Rent Habitable Rooms and 14 per cent Discounted Market Rent Habitable Rooms where the Development provides Build to Rent Units (Site Wide); and

(ii) 93 per cent London Living Rent Habitable Rooms and 7 per cent Discounted Market Rent Habitable Rooms for the East Site; and

(iii) 72 per cent Social Rented Habitable Rooms, 7 per cent London Living Rent Habitable Rooms and 21 per cent Discounted Market Rent Habitable Rooms for the West Site; and

(iv) 50 per cent Social Rented Units and 50 per cent Intermediate Housing Habitable Rooms where the West Site provides Open Market for Sale Units;

…

“Affordable Housing Units – West Site”

means the 165 Residential Units (620 Habitable Rooms) made up of 116 Social Rented Units (448 Habitable Rooms), 12 London Living Rented Units (44 Habitable Rooms) and 37 Discounted Market Rented Units (128 Habitable Rooms) to be constructed upon the West Site pursuant to the Approved Affordable Housing Mix; …

“Net SR Construction Costs”

means the difference between the Social Rented Construction Costs and the total value of the Social Rented Units and non-residential element within the same Building(s) as the Social Rented Units, to be agreed between the parties or determined by the Specialist in accordance with paragraph 3.3 of part 1 of Schedule 3 (Index Linked in accordance with paragraph 3.7 of part 1 of Schedule 3);

…

“Social Rent Equivalent”

means Affordable Housing where maximum weekly rents are set at £155 per 1-bed, £182 per 2-bed, £216 per 3-bed (Index Linked at CPI +1%) on an assured shorthold tenancy for a period of three years with tenant-only break and let to eligible households being those:

- On the Council’s social housing waiting list and in accordance with the Council’s standard nominations protocol for social rented units;

- With no track record of antisocial behaviour or failure to pay rent;

- With satisfactory references;

“Social Rented Construction Costs”

means the cost of constructing (including any demolition required to construct and associated professional fees) 116 Social Rented Units and any non-residential units forming part of the same block as the Social Rented Units;

“Social Rented Housing”

means housing owned and let by local authorities and Registered Providers for which guideline target rents are determined through the national rent regime (meaning the rent regime under which the social rents of tenants of social housing are set by the Regulator with particular reference to the Guidance for Rents on Social Housing May 2014 and the Rent Standard Guidance April 2015);

“Social Rented Units”

means the 116 Affordable Housing Units (22 x 1 bed and 66 x 2 bed and 28 x 3 bed being 450 Habitable Rooms) shown coloured green on the plans attached at Appendix 3b to be provided as Social Rented Housing on the West Site whether or not the Open Market Build to Rent Units – West Site will be provided as Open Market Build to Rent or as Open Market for Sale Units;

…

“Viability Review”

means Viability Review 1, Viability Review 2 and Viability Review 3 as the context permits;

“Viability Review 1” means the upwards only review of the financial viability of the Development at Review 1 Date to determine whether Additional Affordable Housing can be provided on the East Site as part of the Development;

“Viability Review 2” means the upwards only review of the financial viability of the Development at Review 2 Date to determine whether Additional Affordable Housing can be provided on the East Site as part of the Development;

“Viability Review 3” means the upwards only review of the financial viability of the West Site at Review 3 Date to determine whether Additional Affordable Housing can be provided on the West Site as part of the Development;”

31. Schedule 3 of the section 106 obligation addresses those obligations specific to the west site, including those related to affordable housing. Clause 2.1 of the schedule 3 requires that the social rented units shall not be used for any other purpose than as social rented units in perpetuity. Clause 3 of schedule 3 goes on to address the issues in relation to securing completion of the social rented units in the following terms:

“3. Transfer of Land for Social Rented Units

3.1 Paragraphs 3.2 to 3.9 below will only apply in the event that either:

3.1.1 the West Site has not been Substantially Commenced within 10 years following the Development being Implemented on the East Site; or

3.1.2 following Substantial Commencement on the West Site there is a continuous period of inactivity on the West Site for more than six consecutive months, and

3.2 The Council shall notify the Developer that it believes the scenarios in paragraph 3.1 above apply and that the remainder of this paragraph 3 applies.

3.3 The Social Rented Construction Costs, the value of the Social Rented Units and non-residential element within the same Building(s) as the Social Rented Units, and the Net SR Construction Costs shall be agreed between the relevant parties or calculated by reference to a Specialist in accordance with the provisions in clause 20 provided that any value agreed or directed by a Specialist shall be at least the value attributed to those parts of the Development in the Application Viability Appraisal.

3.4 In the event that the Developer has been notified by the Council pursuant to paragraph 3.2 above, the Developer shall notify the Council whether Option 1 below applies.

3.5 In the event that the Developer notifies the Council pursuant to paragraph 3.4 above that Option 1 does not apply, the Council shall determine which of either Option 2 or Option 3 applies:

3.5.1 Option 1

(a) the Developer to construct, or procure the construction of the Social Rented Units and, on Completion, transfer the Completed Social Rented Units to a Registered Provider or the Council.

3.5.2 Option 2

(a) the grant by the Developer to the Council or a Registered Provider the Long Leasehold Interest in the land required for the construction of the Social Rented Units as shown edged red on the plan attached at Appendix 15 in order for the Council or Registered Provider to construct and Complete the Social Rented Units and non-residential floorspace in the same Building(s) as the Social Rented Units; and

(b) the Developer to pay to the Council or Registered Provider the Net SR Construction Costs in accordance with paragraph 3.7 below; or

3.5.3 Option 3

(a) the grant by the Developer to the Council or a Registered Provider the Long Leasehold Interest in the land required for the construction of the Social Rented Units as shown edged red on the plan attached at Appendix 15 in order for the Council or Registered Provider to construct and Complete the Social Rented Units and non-residential floorspace in the same Building(s) as the Social Rented Units, with a payment to the Council or Registered Provider of £1, the cost of constructing the Social Rented Units being reflected by the value of the non-residential floorspace transferred at nil value.

3.6 Following the grant of the Long Leasehold Interest pursuant to paragraphs 3.5.2 and 3.5.3 above, the Developer shall be released from the:

3.6.1 obligations in this Part in relation to the Social Rented Units;

3.6.2 the restriction on Occupation contained in paragraph 1.1 above as far as it relates to the Social Rented Units;

3.6.3 obligations in:

(a) paragraph 2 of Part 4 of Schedule 3;

(b) paragraphs 1 and 2 of Part 6 of Schedule 3; and

(c) paragraph 1 of Part 10 of Schedule 3.

3.7 Only in the event of, and following, the grant of the Long Leasehold Interest pursuant to paragraph 3.5.2 above, the Developer shall pay to the Council or Registered Provider (as applicable) the Net SR Construction Costs (Index Linked from the date that the Net SR Construction Costs are agreed or determined by the Specialist pursuant to paragraph 3.3 above to the date that the relevant payment is made as set out below) as follows:

3.7.1 10% of the Net SR Construction Costs on grant of the Long Leasehold Interest pursuant to paragraph 3.5.2 above;

3.7.2 50% of the Net SR Construction Costs within 20 (twenty) Working Days of being notified by the Council or Registered Provider (as applicable) that it has entered into a build contract for the construction of the Social Rented Units;

3.7.3 40% of the Net SR Construction Costs on the first anniversary of the date that payment was made pursuant to paragraph 3.7.2 above.

3.8 The Council covenants to use the Net SR Construction Costs paid to it pursuant to paragraph 3.7 above only towards the construction of the Social Rented Units and the non-residential floorspace contained in the same Building(s) as the Social Rented Units.

3.9 Should the Developer elect Option 1 above, then the Developer must Complete the Social Rented Units to a standard fit for residential occupation and ready to be transferred to a Registered Provider within 36 (thirty six) months of the date the Developer elects Option 1.

3.10 Should the Council elect Option 2 or Option 3 above, then the Council must construct the Social Rented Units to a standard fit for residential occupation.”

32. Part 3 of schedule 3 to the section 106 obligation addresses the mechanisms applicable to viability reviews. The recital to this part of the section 106 obligation sets out the background to the obligation in the following terms:

“The base viability position that informs this Deed was established by adopting the residual method of valuation. An appraisal of the East Site and West Site was undertaken to establish the maximum reasonable quantum of Affordable Housing that the Development can provide. The agreed Target Return is 11% Ungeared IRR for a Build to Rent scheme and 14% Ungeared IRR for a Build for Sale scheme.

The Developer has offered 35% Affordable Housing but with a mix non-consistent with the emerging policy P4 in the New Southwark Plan, on the basis that the Application Viability Appraisal produces an outturn IRR below the Target Return and in order to provide “traditional” Social Rented Units as requested by the Council rather than social rent equivalent Build to Rent Units.

The Application Viability Appraisal and cashflow is attached at Appendix 10 to this Agreement. It has been agreed that any surplus above the Target Return on any Viability Review will be shared on a 50/50 basis with the portion attributable to the Council translated into Additional Affordable Housing to deliver a mix more consistent with emerging Policy P4 in the New Southwark Plan. The overall provision of Affordable Housing will remain at 35%. It should be recognised however that policy P4 cannot be fully complied with given the delivery at the Council’s request for social rented homes on the site rather than social rent equivalent and that the affordable housing component comprises 38% social rented homes which is higher than the 34% social rent equivalent required under policy P4.”

33. The contentions in the present case revolve around the provisions pertaining to Viability Review 3 in particular. This is the viability review applicable in the event that the Interested Party opts to deliver the west site as open market for sale units rather than open market build to rent units. Schedule 3 of the section 106 obligation provides for a notification mechanism to enable the Interested Party to exercise that option. If the Interested Party adopts the option of delivering the west site as open market for sale units, viability review 3 is triggered to assess whether or not additional affordable housing is required. The section 106 obligation in this respect provides as follows:

“4.2 In the case of a Viability Review, the Council shall assess any submitted Development Viability Information and assess whether in its view Additional Affordable Housing is required to be delivered where the Viability Review shows the Target Return has been exceeded.

…

4.5 The Council shall complete its assessment of the Viability Review and shall notify the Developer whether any Additional Affordable Housing is required within 40 Working Days of the Validation Date.

…

5 Delivery of Additional Affordable Housing

5.1 Where it is determined pursuant to paragraph 4.5 of this Schedule that Additional Affordable Housing is required pursuant to a Viability Review the Developer shall provide such Additional Affordable Housing as soon as reasonably practicable and subject to paragraph 5.2 in any event following the expiry of the second tenancy term after Viability Review 3 has been completed.

5.2 Where the Developer and the Council agree that the Additional Affordable Housing cannot be provided either as a result of a lack of vacant properties on the West Site or as a result that there has been no change in eligibility for tenants which would allow additional reductions in rent charged, the Developer shall pay to the Council the difference between the rent which has been charged and the rent which should have been charged following the provision of the Additional Affordable Housing until the Additional Affordable Housing is provided in accordance with paragraph 5.1.

5.3 The Parties agree that the terms of Schedule 3 (Affordable Housing) shall apply mutatis mutandis to the provision of any Additional Affordable Housing.”

34. During the course of pre-action correspondence, the Defendant and the Interested Party agreed that there was substance in criticisms which had been raised by the Claimant’s solicitors relating to the definition of “Additional Affordable Housing” in the section 106 obligation. As a consequence of accepting these concerns, the Defendant and Interested party entered into a further section 106 obligation in the form of a deed of variation with respect to the original section 106 obligation. This deed of variation was entered into on the 9th July 2019. The effect of the variation was to delete the definition of the term “additional affordable housing” in the original deed and replace it with the following definition:

“Additional Affordable Housing means provision of additional Affordable Housing up to a maximum of the Affordable Housing Cap as follows:

- Following Viability Review 1 or Viability Review 2, additional London Living Rent Habitable Rooms up to a maximum of 389 to be provided on the East Site with a commensurate decrease in the number of Discounted Market Rent Habitable Rooms; or

- Following Viability Review 3, additional London Living Rent Habitable Rooms up to a maximum of 172 to be provided on the West Site with a commensurate decrease in the number of Discounted Market Rent Habitable Rooms; or

- Where the West Site provides Open Market for Sale Units, up to a maximum of 15 additional Social Rent Equivalent habitable rooms to be provided on the West Site with a commensurate decrease in the number of Intermediate Housing habitable rooms”.”

35. The Defendant arrived at a calculation of 15 additional rooms following a discussion between the Defendant’s officers and the Interested Party’s planning consultants. In an email of the 30th October 2018 the Defendant’s planning officer set out her calculation of the impact on affordable housing provision of delivering the west site as a build to sell proposal in the following terms:

“The scenario I was describing at the meeting yesterday relates to how the affordable housing for the west site should be calculated under a build to sell scenario.

There are 1,603 habitable rooms on the east site, 12% of which (192 hab rooms) should have been SR equivalent under emerging policy P4. These were all provided on the west site as SR units however, similar to an off-site contribution. As such if the west site is delivered as build to sell, these 192 hab rooms should be ringfenced because they related to the east site. The AH requirement for the west site should then be calculated based on the remaining hab rooms. There are 1,754 hab rooms on the west site, minus the 192 SR hab rooms which belong to the east site which leaves 1,562 hab rooms remaining. Of these, 35% (547) should be affordable, comprising of 273 SR and 273 intermediate i.e. a 50/50 split as per Saved Policy 4.4 of the Southwark Plan. This is what a build to sell should aim for, although the actual provision would be based on a viability review.”

36. The response from the Interested Party’s planning consultant sought to use this calculation to identify the shortfall arising from the Interested Party taking up the option of delivering the west site as a build to sell development and the shortfall of 15 habitable rooms is described in the email by way of reply written on the 8th November 2018:

“Working off your numbers though, and taking your requirement for 273/273 on the west site (SR/int), unless I’m missing something, the social rent block is providing the 192 HRs you refer to for the east site but also an additional 258 (there are 450 HRs of social rent by my count). Therefore, if the west site is delivered as social rent then the shortfall would only be 15 HRs ie 273 headline requirement less 258 being provided?”

This exchange of emails explains the reference in the deed variation to 15 additional social rent equivalent habitable rooms.

The Claimant’s grounds

37. Against the background of the facts set out above the Claimant advances three grounds of challenge by way of judicial review. The first ground of challenge is the contention that the Defendant’s decision to grant planning permission is infected by an error of law based upon the contents of the officers’ report. The error of law is characterised in two ways. Firstly, it is contended that the decision is vitiated by an error of fact which satisfies the relevant legal tests to establish it as an error of law. Alternatively, and in a related fashion, it is contended that the officers’ report materially and significantly misled the members of the planning committee, such that their decision was, again, infected by an error of law. The focus of the Claimant’s contention is the text of paragraph 371 of the officers’ report. In this paragraph, as set out above, the officers advised members that the improved offer of 116 social rented units was a proposal which “reflects GLA grant funding, recently confirmed, which has facilitated an increase in the number of social rented units from 74 to 116.” The Claimant contends that this observation was both factually erroneous and also misleading. It is clear from the correspondence with the GLA that in fact grant funding for the housing had not been applied for, let alone been “recently confirmed”. Furthermore, the increased offer in the number of social rented units had not been facilitated by grant funding at all. Had members been aware of the reality of the position, namely that grant funding had neither been secured, nor had it facilitated an increase in the offer which was made and underwritten by the Interested Party, then members may well have pursued a different approach, and sought to force a further increase in the provision of social rented accommodation from the Interested Party on the basis that even with this increase the offer which was being made was not one which was policy compliant. Alternatively, had they known that the affordable housing offer was not facilitated by recently confirmed grant funding then they may have sought to refuse permission on the basis that the scheme could not be delivered as it was unviable.

38. In response to these submissions the Defendant and the Interested Party contend that once paragraph 371 is read alongside the material contained in the addendum report it is plain that the advice to members was neither misleading nor mistaken. It was clear to members that grant funding was simply agreed in principle, and that the risk of grant not arising was being borne by the Interested Party who had committed to providing 116 social rented units whether or not grant funding materialised. Furthermore, it is contended, in particular on behalf of the Interested Party, that a failure to provide a still further improved offer in respect of social rented housing could not have amounted to a proper reason to refuse planning permission, in circumstances where the undisputed evidence in relation to viability demonstrated that scheme provided the maximum affordable housing that the development could reasonably support. Furthermore, members had been advised that the scheme, albeit complex, was one which was deliverable. Thus, members were not misled and the report was not mistaken; in any event there is no reason to assume that there would have been any different practical outcome in relation to this issue.