DANIEL ALEXANDER QC

INTRODUCTION

- This is an appeal from the decision of Ms Judi Pike, acting for the Registrar, in consolidated proceedings for

a. revocation of two international trade mark registrations of which the key element is the word ABANKA, owned by the appellant, Abanka d.d. ("Abanka") and

b. opposition based on those marks against an application for registration of the trade mark ABANCA in stylized form filed by the respondent, Abanca Corporación Bancaria S.A. ("Abanca").

The marks in issue

- The marks ABANKA (in colour and in black and white or no colour) are international trade mark registrations (numbers 860632 and 860561, respectively) in classes 35, 36 and 38 have been protected in the UK since they completed their registration procedures on 17 March and 24 March 2006, respectively. Their specifications were set out in the annex to the hearing officer's decision and they cover a very wide range of financial services. It is not necessary to set all of these out at this stage.

Use of the marks

- It was not in dispute that there had been no use in relation to a wide range of the services in question. The central issue in the case is whether the activities of Abanka constitute use of the marks in the UK sufficient to support the continued registration of the marks in respect of some or all of the remainder. The hearing officer held that no use had been proved in the relevant periods with the consequence that the marks were revoked and could not be relied on as a basis for opposition to the registration of the marks ABANCA by Abanca. Accordingly, she also dismissed the opposition.

- As to that opposition, Abanka opposes Abanca's request for protection of ABANCA in classes 9, 16, 35, 36 and 38 only under section 5(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 ("the Act"), claiming a likelihood of confusion with the earlier ABANKA marks which are the subject of the applications for revocation. The hearing officer did not ultimately need to decide whether or not the marks ABANCA in its particular stylized form and font and ABANKA in the form in which it was registered sufficiently similar so as to give rise to a likelihood of confusion in respect of any of the goods or services for which registration of the ABANCA mark was sought, since the earlier registrations were revoked. That removed the whole basis for the oppositions. It is of some significance for what follows that Abanka did not challenge the registration of the stylized ABANCA mark on the basis of section 5(4) of the Act (alleging passing off) or suggest that it had built up sufficient goodwill in the UK as a result of its activities to do so. Nonetheless, it contends that the law relating to use of trade marks entitles it to preserve its registrations.

- There is no dispute as to the relevant periods in respect of which use must be considered and no dispute as to the primary facts, although Abanca invited the hearing officer and this court on appeal to look at some of the evidence of use with a sceptical eye. The real issue is whether, assuming the primary facts as found by the hearing officer are proved, such constitutes use in the UK sufficient to maintain the registrations to any and, if so, what extent.

LAW

Statutory framework

- Section 46 of the Act provides:

"(1) The registration of a trade mark may be revoked on any of the following grounds—

(a) that within the period of five years following the date of completion of the registration procedure it has not been put to genuine use in the United Kingdom, by the proprietor or with his consent, in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered, and there are no proper reasons for non-use;

(b) that such use has been suspended for an uninterrupted period of five years, and there are no proper reasons for non-use;

(c) that, in consequence of acts or inactivity of the proprietor, it has become the common name in the trade for a product or service for which it is registered;

(d) that in consequence of the use made of it by the proprietor or with his consent in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered, it is liable to mislead the public, particularly as to the nature, quality or geographical origin of those goods or services.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1) use of a trade mark includes use in a form differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of the mark in the form in which it was registered, and use in the United Kingdom includes affixing the trade mark to goods or to the packaging of goods in the United Kingdom solely for export purposes.

(3) The registration of a trade mark shall not be revoked on the ground mentioned in subsection (1)(a) or (b) if such use as is referred to in that paragraph is commenced or resumed after the expiry of the five year period and before the application for revocation is made.

Provided that, any such commencement or resumption of use after the expiry of the five year period but within the period of three months before the making of the application shall be disregarded unless preparations for the commencement or resumption began before the proprietor became aware that the application might be made.

(4) An application for revocation may be made by any person, and may be made either to the registrar or to the court, except that——

(a) if proceedings concerning the trade mark in question are pending in the court, the application must be made to the court; and

(b) if in any other case the application is made to the registrar, he may at any stage of the proceedings refer the application to the court.

(5) Where grounds for revocation exist in respect of only some of the goods or services for which the trade mark is registered, revocation shall relate to those goods or services only.

(6) Where the registration of a trade mark is revoked to any extent, the rights of the proprietor shall be deemed to have ceased to that extent as from——

(a) the date of the application for revocation, or

(b) if the registrar or court is satisfied that the grounds for revocation existed at an earlier date, that date."

- The onus is on the proprietor to prove use. Section 100 of the Act provides:

"If in any civil proceedings under this Act a question arises as to the use to which a registered trade mark has been put, it is for the proprietor to show what use has been made of it."

Proof of use – general

- The hearing officer took the summary of the relevant principles from The London Taxi Corporation Ltd (t/a The London Taxi Company) v. Fraser-Nash Research Ltd & another [2016] EWHC 52 (Ch) at [217]-[219] as follows:

"217. In Stichting BDO v BDO Unibank Inc [2013] EWHC 418 (Ch), [2013] FSR 35 I set out at [51] a helpful summary by Anna Carboni sitting as the Appointed Person in SANT AMBROEUS Trade Mark [2010] RPC 28 at [42] of the jurisprudence of the CJEU in Case C-40/01 Ansul BV v Ajax Brandbeveiliging BV [2003] ECR I-2439, Case C-259/02 La Mer Technology Inc v Laboratories Goemar SA [2004] ECR I-1159 and Case C-495/07 Silberquelle GmbH v Maselli-Strickmode GmbH [2009] ECR I-2759 (to which I added references to Case C-416/04 P Sunrider Corp v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) [2006] ECR I-4237). I also referred at [52] to the judgment of the CJEU in Case C-149/11 Leno Merken BV v Hagelkruis Beheer BV [EU:C:2012:816], [2013] ETMR 16 on the question of the territorial extent of the use. Since then the CJEU has issued a reasoned Order in Case C-141/13 P Reber Holding & Co KG v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) [EU:C:2014:2089] and that Order has been persuasively analysed by Professor Ruth Annand sitting as the Appointed Person in SdS InvestCorp AG v Memory Opticians Ltd (O/528/15).

[218] ...

219. I would now summarise the principles for the assessment of whether there has been genuine use of a trade mark established by the case law of the Court of Justice, which also includes Case C-442/07 Verein Radetsky- Order v Bundervsvereinigung Kamaradschaft 'Feldmarschall Radetsky' [2008] ECR I-9223 and Case C-609/11 Centrotherm Systemtechnik GmbH v Centrotherm Clean Solutions GmbH & Co KG [EU:C:2013:592], [2014] ETMR 7, as follows:

(1) Genuine use means actual use of the trade mark by the proprietor or by a third party with authority to use the mark: Ansul at [35] and [37].

(2) The use must be more than merely token, that is to say, serving solely to preserve the rights conferred by the registration of the mark: Ansul at [36]; Sunrider at [70]; Verein at [13]; Centrotherm at [71]; Leno at [29].

(3) The use must be consistent with the essential function of a trade mark, which is to guarantee the identity of the origin of the goods or services to the consumer or end user by enabling him to distinguish the goods or services from others which have another origin: Ansul at [36]; Sunrider at [70]; Verein at [13]; Silberquelle at [17]; Centrotherm at [71]; Leno at [29].

(4) Use of the mark must relate to goods or services which are already marketed or which are about to be marketed and for which preparations to secure customers are under way, particularly in the form of advertising campaigns: Ansul at [37]. Internal use by the proprietor does not suffice: Ansul at [37]; Verein at [14]. Nor does the distribution of promotional items as a reward for the purchase of other goods and to encourage the sale of the latter: Silberquelle at [20]-[21]. But use by a non-profit making association can constitute genuine use: Verein at [16]-[23].

(5) The use must be by way of real commercial exploitation of the mark on the market for the relevant goods or services, that is to say, use in accordance with the commercial raison d'e^tre of the mark, which is to create or preserve an outlet for the goods or services that bear the mark: Ansul at [37]-[38]; Verein at [14]; Silberquelle at [18]; Centrotherm at [71].

(6) All the relevant facts and circumstances must be taken into account in determining whether there is real commercial exploitation of the mark, including: (a) whether such use is viewed as warranted in the economic sector concerned to maintain or create a share in the market for the goods and services in question; (b) the nature of the goods or services; (c) the characteristics of the market concerned; (d) the scale and frequency of use of the mark; (e) whether the mark is used for the purpose of marketing all the goods and services covered by the mark or just some of them; (f) the evidence that the proprietor is able to provide; and (g) the territorial extent of the use: Ansul at [38] and [39]; La Mer at [22]-[23]; Sunrider at [70]-[71], [76]; Centrotherm at [72]-[76]; Reber at [29], [32]-[34]; Leno at [29]-[30], [56].

(7) Use of the mark need not always be quantitatively significant for it to be deemed genuine. Even minimal use may qualify as genuine use if it is deemed to be justified in the economic sector concerned for the purpose of creating or preserving market share for the relevant goods or services. For example, use of the mark by a single client which imports the relevant goods can be sufficient to demonstrate that such use is genuine, if it appears that the import operation has a genuine commercial justification for the proprietor. Thus there is no de minimis rule: Ansul at [39]; La Mer at [21], [24] and [25]; Sunrider at [72]; Leno at [55].

(8) It is not the case that every proven commercial use of the mark may automatically be deemed to constitute genuine use: Reber at [32]."

- Neither side took issue with this approach.

Use in the United Kingdom

- Arnold J summarised the principles relevant to determining whether use had been undertaken in the UK in the context of an allegation of infringement in Stichting BDO as follows:

"The law

100. The case law of the CJEU establishes that the proprietor of a Community trade mark can only succeed in a claim under Article 9(1)(a) of the Regulation if six conditions are satisfied: (i) there must be use of a sign by a third party within the European Union; (ii) the use must be in the course of trade; (iii) it must be without the consent of the proprietor of the trade mark; (iv) it must be of a sign which is identical to the trade mark; (v) it must be in relation to goods or services which are identical to those for which the trade mark is registered; and (vi) it must affect or be liable to affect the functions of the trade mark: see in particular Case C-206/01 Arsenal Football plc v Reed [2002] ECR I-10273 at [51], Case C-245/02 Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budejovicky Budvar np [2004] I-10989 at [59], Case C-48/05 Adam Opel AG v Autec AG [2007] ECR I-1017 at [18]-[22] and Case C-17/06 Céline SARL v Céline SA [2007] ECR I-7041 at [16].

101. The first condition. The correct approach to the question of whether there has been use of the sign within the European Union was considered by the CJEU in the context of offers for sale on an online marketplace in Case C-324/09 L'Oréal SA v eBay International AG [2011] ECR I-0000, [2012] EMLR 6. In that case the Court held as follows:

"61. Whilst recognising those principles, eBay submits that the proprietor of a trade mark registered in a Member State or of a Community trade mark cannot properly rely on the exclusive right conferred by that trade mark as long as the goods bearing it and offered for sale on an online marketplace are located in a third State and will not necessarily be forwarded to the territory covered by the trade mark in question. L'Oréal, the United Kingdom Government, the Italian, Polish and Portuguese Governments, and the European Commission contend, however, that the rules of Directive 89/104 and Regulation No 40/94 apply as soon as it is clear that the offer for sale of a trade-marked product located in a third State is targeted at consumers in the territory covered by the trade mark.

62. The latter contention must be accepted. If it were otherwise, operators which use electronic commerce by offering for sale, on an online market place targeted at consumers within the EU, trade-marked goods located in a third State, which it is possible to view on the screen and to order via that marketplace, would, so far as offers for sale of that type are concerned, have no obligation to comply with the EU intellectual property rules. Such a situation would have an impact on the effectiveness (effet utile) of those rules.

63. It is sufficient to state in that regard that, under Article 5(3)(b) and (d) of Directive 89/104 and Article 9(2)(b) and (d) of Regulation No 40/94, the use by third parties of signs identical with or similar to trade marks which proprietors of those marks may prevent includes the use of such signs in offers for sale and advertising. As the Advocate General observed at point 127 of his Opinion and as the Commission pointed out in its written observations, the effectiveness of those rules would be undermined if they were not to apply to the use, in an internet offer for sale or advertisement targeted at consumers within the EU, of a sign identical with or similar to a trade mark registered in the EU merely because the third party behind that offer or advertisement is established in a third State, because the server of the internet site used by the third party is located in such a State or because the product that is the subject of the offer or the advertisement is located in a third State.

64. It must, however, be made clear that the mere fact that a website is accessible from the territory covered by the trade mark is not a sufficient basis for concluding that the offers for sale displayed there are targeted at consumers in that territory (see, by analogy, Joined Cases C-585/08 and C-144/09 Pammer and Hotel Alpenhof [2010] ECR I-0000, paragraph 69). Indeed, if the fact that an online marketplace is accessible from that territory were sufficient for the advertisements displayed there to be within the scope of Directive 89/104 and Regulation No 40/94, websites and advertisements which, although obviously targeted solely at consumers in third States, are nevertheless technically accessible from EU territory would wrongly be subject to EU law.

65. It therefore falls to the national courts to assess on a case-by-case basis whether there are any relevant factors on the basis of which it may be concluded that an offer for sale, displayed on an online marketplace accessible from the territory covered by the trade mark, is targeted at consumers in that territory. When the offer for sale is accompanied by details of the geographic areas to which the seller is willing to dispatch the product, that type of detail is of particular importance in the said assessment."

102. Joined Cases C-585/08 and C-144/09 Pammer v Reederei Karl Schlüter GmbH & Co. KG and Hotel Alpenhof GesmbH v Heller [2010] ECR I-12527, to which reference is made at [64], concerned the interpretation of Article 15(1)(c) of Council Regulation 44/2001/EC of 22 December 2000 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters ("the Brussels I Regulation"), and in particular the requirement that "the contract has been concluded with a person who pursues commercial or professional activities in the member state of the consumer's domicile or, by any means, directs such activities to that member state". The CJEU interpreted the national court as asking, in essence, "on the basis of what criteria a trader whose activity is presented on its website or on that of an intermediary can be considered to be 'directing' its activity to the Member State of the consumer's domicile …, and second, whether the fact that those sites can be consulted on the internet is sufficient for that activity to be regarded as such".

103. The Court held at [69]-[75] that it was not sufficient for this purpose that a website was accessible in Member States other than that in which the trader concerned was established: "the trader must have manifested its intention to establish commercial relations with consumers from one or more other Member States, including that of the consumer's domicile". It went on at [80]-[81] to say that relevant evidence on the point would be "all clear expressions of the intention to solicit the custom of that state's customers". Such a clear expression could include actual mention of the fact that it is offering its services or goods "in one or more Member States designated by name" or payments to "the operator of a search engine in order to facilitate access to the trader's site by consumers domiciled in various member states".

104. The CJEU concluded at [93]:

"The following matters, the list of which is not exhaustive, are capable of constituting evidence from which it may be concluded that the trader's activity is directed to the Member State of the consumer's domicile, namely the international nature of the activity, mention of itineraries from other Member States for going to the place where the trader is established, use of a language or a currency other than the language or currency generally used in the Member State in which the trader is established with the possibility of making and confirming the reservation in that other language, mention of telephone numbers with an international code, outlay of expenditure on an internet referencing service in order to facilitate access to the trader's site or that of its intermediary by consumers domiciled in other Member States, use of a top-level domain name other than that of the Member State in which the trader is established, and mention of an international clientele composed of customers domiciled in various Member States. It is for the national courts to ascertain whether such evidence exists."

105. In my judgment these matters are also capable of constituting evidence which bears upon the question of whether an offer for sale or an advertisement on a website is targeted at consumers within the European Union for the purposes of the first condition under Article 9(1)(a). It is perhaps worth emphasising that, at least in this context, the question is not one of the subjective intention of the advertiser, but rather one of the objective effect of its conduct viewed from the perspective of the average consumer.

106. Both L'Oréal v eBay and Pammer and Hotel Alpenhof were cases concerned with websites. It is common ground that the test of targeting the consumer in the relevant territory adopted by the CJEU in L'Oréal v eBay is essentially the same approach as had previously been adopted with regard to websites by the courts of this country: see Euromarket Designs Inc v Peters [2001] FSR 20 at [21]-[25], 1-800 Flowers v Phonenames [2001] EWCA Civ 721, [2002] FSR 12 at [136]-[139] and Dearlove v Combs [2007] EWHC 375 (Ch), [2008] EMLR 2 at [21]-[25].

107. Euromarket v Peters also concerned an advertisement in a magazine. The claimant, which ran a chain of shops selling household goods and furniture in the USA, applied for summary judgment on a claim for infringement of its UK registered trade mark for the words CRATE & BARREL. The defendants ran a shop in Dublin selling household goods and furniture under the same sign. One of the alleged infringements consisted of an advertisement placed by the defendants in the magazine Homes & Gardens. Jacob J set out the relevant facts as follows:

"10. Homes & Gardens is a United Kingdom published magazine. The defendants had a single full page colour advertisement. At the top in large letters are words 'Crate & Barrel', beneath are two colour photographs, beneath them is the word "Dublin", in the same large size and lettering. One reads the words naturally as 'Crate & Barrel, Dublin'. In much smaller letters the advertisement goes on to say 'soft furnishings: Orior by Design, furniture: Chalon'. In even smaller print at the bottom, the advertisement says 'sofas, tableware, beds, lighting accessories'. Underneath that a website address is given, 'www.crateandbarrel-ie.com.' 'ie' is webspeak for Ireland. A telephone/fax number is given with the full international code for Ireland.

11. Ms Peters says the advertisement was placed on the recommendation of the furniture supplier, Chalon. It was Chalon who actually placed the advertisement because they could get a better rate. Homes & Gardens was chosen because it is widely sold in the Republic and there is no exclusively Irish high quality interior furnishings magazine. The international dialling code was the idea of the photographer who caused it to be used on his own initiative and without the knowledge of Ms Peters. She says that although she knew that Homes & Gardens has a substantial United Kingdom circulation, she never expected or intended to obtain United Kingdom customers. She says the defendants have never sold any products in or to the United Kingdom. Doubtless they have sold some products in their Dublin shop to visitors from the United Kingdom."

108. Jacob J expressed the provisional view that this was not infringing use for reasons he expressed as follows:

"16. … I think there must be an inquiry as to what the purpose and effect of the advertisement in question is. In the present case, for example, the advertisement tells a reader, who knows nothing more, that there is an enterprise called 'Crate & Barrel' in Dublin dealing with the goods mentioned. It is probably a shop, for these are not the sort of goods one would order only by mail. Normally, of course, an advertisement placed in a United Kingdom magazine is intended to drum up United Kingdom business and will do so. This is so whether the advertisement is for goods or for a service or shop. But this is not a normal case. This is an advertisement for an Irish shop in a magazine which has an Irish and United Kingdom circulation.

….

18. … It is Article 5 which sets out the obligatory and optional provisions as to what constitutes infringement. It is Article 5 which uses the expression 'using in the course of trade … in relation to goods or services' from which section 10 of the United Kingdom Act is derived.

19. The phrase is a composite. The right question, I think, is to ask whether a reasonable trader would regard the use concerned as 'in the course of trade in relation to goods' within the Member State concerned. Thus if a trader from state X is trying to sell goods or services into state Y, most people would regard that as having a sufficient link with state Y to be 'in the course of trade' there. But if the trader is merely carrying on business in X, and an advertisement of his slips over the border into Y, no businessman would regard that fact as meaning that he was trading in Y. This would especially be so if the advertisement were for a local business such as a shop or a local service rather than for goods. I think this conclusion follows from the fact that the Directive is concerned with what national law is to be, that it is a law governing what traders cannot do, and that it is unlikely that the Directive would set out to create conflict within the internal market. … One needs to ask whether the defendant has any trade here, customers buying goods or services for consumption here. …"

109. In my judgment the factors referred to in L'Oréal v eBay and Pammer and Hotel Alpenhof are, with the exception of those which only relate to the online environment, equally relevant when considering a print advertisement. In addition, however, the nature of the publication and the territories in which it circulates are also relevant factors to take into account."

- It can often be a difficult question to decide where any given use of a mark should be taken to have occurred and, in particular, whether it has taken place in the UK. Such an issue crops up in the context of infringement as well as in non-use case and, in principle, the approach to the issue of territorial location of use should be the same. However, in the context of allegations of non-use, in contrast to infringement, that issue is also overlaid with questions of whether such use as has been proven can be regarded as sufficiently substantial to be evidence of genuineness of use. Whereas, in principle, a single use in the UK of a mark by a third party in relation to goods for which the mark is registered may constitute infringement, it does not follow that such an isolated use by the proprietor would invariably suffice to support continued registration of a trade mark.

Approach to evidence of use

- In Plymouth Life Centre, O/236/13, when sitting as the Appointed Person, I said, at para. 20:

"The burden lies on the registered proprietor to prove use.......... However, it is not strictly necessary to exhibit any particular kind of documentation, but if it is likely that such material would exist and little or none is provided, a tribunal will be justified in rejecting the evidence as insufficiently solid. That is all the more so since the nature and extent of use is likely to be particularly well known to the proprietor itself. A tribunal is entitled to be sceptical of a case of use if, notwithstanding the ease with which it could have been convincingly demonstrated, the material actually provided is inconclusive. By the time the tribunal (which in many cases will be the Hearing Officer in the first instance) comes to take its final decision, the evidence must be sufficiently solid and specific to enable the evaluation of the scope of protection to which the proprietor is legitimately entitled to be properly and fairly undertaken, having regard to the interests of the proprietor, the opponent and, it should be said, the public."

- The hearing officer referred to this passage and neither side on this appeal took issue with it.

THE APPEAL

- The hearing officer held that the earlier marks should be revoked for non-use in their entirety with effect from 7 May 2014. The Notice of Appeal filed on 3 January 2017 sought an order setting aside the decision of the hearing officer and did not seek any other order although implicit in it was the contention that the trade mark Abanca had applied for should be refused. The Grounds of Appeal focussed solely on the issue of revocation of Abanka's mark.

- In my view, that was appropriate since, on the assumption that the court takes the view that use has been proven to any extent, two further issues arise: (a) what description of services would be appropriate in the light of the findings of use? and (b) what consequences there are for other aspects of the case, in particular, the opposition? Those would require separate argument and submission, including as to whether or the extent to which any of those issues should be remitted for initial consideration by the Registrar. This appeal therefore focussed on the question of proof of use alone.

APPROACH TO APPEALS TO THE HIGH COURT FROM THE REGISTRAR

- In Apple Inc v Arcadia Trading Ltd [2017] EWHC 440 (Ch) (10 March 2017), Arnold J said at [11]:

"Standard of review

The principles applicable on an appeal from the Registrar of Trade Mark were recently considered in detail by Daniel Alexander QC sitting as the Appointed Person in TT Education Ltd v Pie Corbett Consultancy Ltd (O/017/17) at [14]-[52]. Neither party took issue with his summary at [52], which is equally applicable in this jurisdiction:

"(i) Appeals to the Appointed Person are limited to a review of the decision of Registrar (CPR 52.11). The Appointed Person will overturn a decision of the Registrar if, but only if, it is wrong (Patents Act 1977, CPR 52.11).

(ii) The approach required depends on the nature of decision in question (REEF). There is spectrum of appropriate respect for the Registrar's determination depending on the nature of the decision. At one end of the spectrum are decisions of primary fact reached after an evaluation of oral evidence where credibility is in issue and purely discretionary decisions. Further along the spectrum are multi-factorial decisions often dependent on inferences and an analysis of documentary material (REEF, DuPont).

(iii) In the case of conclusions on primary facts it is only in a rare case, such as where that conclusion was one for which there was no evidence in support, which was based on a misunderstanding of the evidence, or which no reasonable judge could have reached, that the Appointed Person should interfere with it (Re: B and others).

(iv) In the case of a multifactorial assessment or evaluation, the Appointed Person should show a real reluctance, but not the very highest degree of reluctance, to interfere in the absence of a distinct and material error of principle. Special caution is required before overturning such decisions. In particular, where an Appointed Person has doubts as to whether the Registrar was right, he or she should consider with particular care whether the decision really was wrong or whether it is just not one which the appellate court would have made in a situation where reasonable people may differ as to the outcome of such a multifactorial evaluation (REEF, BUD, Fine & Country and others).

(v) Situations where the Registrar's decision will be treated as wrong encompass those in which a decision is (a) unsupportable, (b) simply wrong (c) where the view expressed by the Registrar is one about which the Appointed Person is doubtful but, on balance, concludes was wrong. It is not necessary for the degree of error to be 'clearly' or 'plainly' wrong to warrant appellate interference but mere doubt about the decision will not suffice. However, in the case of a doubtful decision, if and only if, after anxious consideration, the Appointed Person adheres to his or her view that the Registrar's decision was wrong, should the appeal be allowed (Re: B).

(vi) The Appointed Person should not treat a decision as containing an error of principle simply because of a belief that the decision could have been better expressed. Appellate courts should not rush to find misdirections warranting reversal simply because they might have reached a different conclusion on the facts or expressed themselves differently. Moreover, in evaluating the evidence the Appointed Person is entitled to assume, absent good reason to the contrary, that the Registrar has taken all of the evidence into account. (REEF, Henderson and others)."

- The High Court has adopted that summary in other recent cases (see e.g. The Royal Mint Ltd v The Commonwealth Mint And Philatelic Bureau Ltd [2017] EWHC 417 (Ch) (03 March 2017)). However, the question of appellate approach in trade mark appeals has been revisited since the hearing in this case in CCHG Ltd (t/a Vaporized) v Vapouriz Ltd [2017] ScotCS CSOH_100 (12 July 2017) ("Vaporized"), the first appeal on the merits under the Act made to the Outer House of the Court of Session. That decision mainly considers whether the approach to trade mark appeals of this kind before that court differs to any extent to that applicable in England and Wales as a result of rule 55.19(10) of the Rules of the Court of Session (which provide that an appeal "shall be a rehearing and the evidence led on appeal shall be the same as that led before the Comptroller…"; the corresponding English rule under the Rule 52 CPR provides that such an appeal shall be by way of "review").

- In Vaporized, Lady Wolffe concluded that this difference in wording made no difference to the substantive approach in Scotland. However, of potential relevance to the present case, there was also debate before Lady Wolffe as to whether the Appointed Person in TT Education Limited had, as it was argued, "recanted" from the approach of the High Court in Digipos as it happens, both decisions of mine sitting in different capacities. She said of the summary of principles in TT Education Limited cited above:

"[98]…Apart from summary principle (i), which restates the terms of CPR 52.11, principles (ii) to (vi) of paragraph 52 of TT Education Limited reflect the preponderance of the cases that appellate courts exercise an appropriate restraint. Notwithstanding his dropping of the qualifier "plainly" in sub-paragraph (v), when that sub-paragraph is read in the context of his other principles, and consistently with the case-law he had just examined, the effect of dropping "plainly" may be less significant in practice than Ms Pickard contends for. In other words, in the application of these different formulations there is unlikely to be a real difference in outcome between the two jurisdictions when an appellate court is reviewing the multi-factorial assessment of a hearing officer and in the absence of any identifiable error. Therefore, there is in my view no material divergence in approach as between Scotland or England in relation to the nature of appeals from the decisions of hearing officers or the test to be applied to such appeals.

[99] In relation to Ms Pickard's suggestion that in TT Education Limited Mr Alexander QC had recanted from his observations in Digipos, I do not accept this submission. His observation in Digipos (set out at para [57], above), to the effect that criticisms that a hearing officer attributed too much or too little weight to certain factors are not errors of principle warranting interference, is wholly consistent with his observations in TT Education Limited. Further, this observation in Digipos accords entirely with the nature of the multi-factorial assessment discussed in the case-law. Accordingly, I proceed on the basis that an appeal against a multi-factorial assessment of the likelihood of confusion for the purposes of section 5(2) of the TMA 1994 can only succeed where a distinct error of principle is shown or where the decision is plainly wrong."

- With respect to Lady Wolffe, she is right. TT Education Limited does not represent a substantive retreat from Digipos. The debate in TT Education Limited centered on whether the decision of the Supreme Court in Re:B, which contained guidance of potentially general application to appeals and which earlier decisions had suggested may have had an impact on appeals from the Registrar (see e.g. the decision of the Appointed Person, Mr Geoffrey Hobbs QC, in ALDI GmbH v Sig Trading O-169-16) had materially affected the approach to appeals against decisions of multifactorial issues in trade mark matters. I concluded that it had not and that the bar remained where Reef and other cases had put it, namely high. That approach has been followed in later cases.

"Wrong" or "clearly/plainly wrong"?

- While I particularly endorse the observations of Mr Iain Purvis QC sitting as the Appointed Person in Rochester TM O-049-17 that sufficient ink has been spilled on this topic by various tribunals, in the light of the further discussion in Vaporized on the topic, it is worth adding a few words of explanation of the "wrong"/"plainly wrong" debate.

- Whether to describe a decision which merits reversal as "wrong", "clearly wrong", "plainly wrong", or any other kind of wrong, risks elevating language over substance. As I noted in TT Education Limited, some courts have preferred to use the term "plainly wrong" (The decision of the Appointed Person in Rochester TM is another example since TT Education Limited) where Mr Iain Purvis QC said at [31]:

"I therefore believe that the phrases 'plainly wrong' or 'clearly wrong' are still legitimate phrases to use when considering whether to overturn a decision on an evaluative issue which is as indeterminate and open to debate as the question of likelihood of confusion."

- That view is justified, not least in view of the summary of the principles by Floyd J in Galileo International Technology LLC v. European Union [2011] EWHC 35 [2011] ETMR 22 who said at [14] that he should interfere,

"…if I consider that his decision is clearly wrong, for example if I consider that he has drawn inferences which cannot properly be drawn, or has otherwise reached an unreasonable conclusion. I should not interfere if his decision is one which he was properly entitled to reach on the material before him" (and see also Healey Sports Cars Switzerland Ltd v. Jensen Cars Ltd [2014] EWHC 24 (Pat) [2014] ETMR 18 applied in JUMPMAN (Nike Innovate C.V.'s TM Application) O-222-16 [2017] FSR 8).

- Others courts have indicated, in the context of the issues they were considering, that such terminology is better avoided. Regardless of the language used, the real question, as all the cases say, is whether the decision in question was wrong in principle or was outside the range of views which could reasonably be taken on the facts (to adopt the formulation in Rochester at [34]). It is important not to let discussion over qualifiers of this kind distract from the central idea of appellate restraint, expressed throughout the case law: a tribunal should not conclude that a decision is wrong, simply because it would not have decided the matter that way. That is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for appellate reversal. The English (and in the light of Vaporized, Scottish) approach provides for appellate discipline in situations where there is no reason to consider that an appellate tribunal is better placed to make the evaluation than the Registrar from whom the appeal is brought. Against that background, the use of the term "plainly wrong" or "clearly wrong" can serve as a reminder of the height of the bar, without acting as a straightjacket for appellate tribunals.

- Finally on this issue, I noted in JUMPMAN that re-evaluating non-use decisions of the Registrar on the footing that they had set the bar of substantiality of proven use too high in the case where, on any view, the use had been tiny, needed to be treated with particular care (see paras. [92]-[95]).

- I have therefore approached the case on the basis that I should be cautious about overturning evaluations by the hearing officer of the adequacy or sufficiency of evidence of use where reasonable people may differ as to its probative value or significance as indicating genuine use, including evaluations of whether particular internet use was targeted at the UK.

USE OF THE MARKS

- Turning to the substance of the appeal, it is convenient to consider the contentions under the respective heads of use alleged individually. That is because use has to be proved with respect to certain specific kinds of goods or services. In attempting to prove use in category A, it does not help to show there has been use in category B (save to the extent that the contention is that the use has not been bona fide, where a pattern of related use may suggest the contrary). Such was not alleged in this case.

Abanka's position as a Slovenian bank

- However, before addressing the individual heads of use, it is important to note, as the hearing officer did, that the evidence clearly showed that Abanka was a Slovenian bank. It does not have a UK banking licence and the focus of Abanka's activites lay in Slovenia, with only very minor activities in the UK in the context of the UK banking sector as a whole. Moreover, much of that activity appeared to be centered on serving the expatriate Slovenian community in the UK. There was no evidence that it was possible to open an account with Abanka from the UK although it was possible to undertake internet banking once opened.

- The hearing officer summarised the position as follows:

"33. The present case is concerned with the UK banking sector. This is, self- evidently, a huge market. The proprietor is best placed to show evidence that, in the relevant periods, it was engaged in maintaining or creating a share in that market. However, the evidence which it has provided is patchy. For instance, the 80 card owners in the UK are not matched to the transactions, presumably because they are not, in fact, transactions wholly made by the UK card holders. If they were, the level of spend would be surprisingly large. Therefore, the transaction evidence has little, if any, relevance because it is impossible to know the proportion of it which relates to the UK card holders. The debit and credit card evidence comes down to 80 holders over 6 years. This is a vanishingly small amount of business in the sector concerned and begs the question as to how the proprietor has commercially engaged with those 80, and why there are not more than 80 card holders.

34. The answer to that question lies in the picture which emerges from the rest of the evidence. I have already mentioned the press release which refers to the proprietor as being the best bank in Slovenia (only). The flotation on the London Stock Exchange was to raise funds for the proprietor itself. The final page of the memorandum states that the proprietor derives its information for the memorandum from the Republic of Slovenia, the Slovenian banking market and its competitors. These two pieces of evidence place the proprietor's business as being in Slovenia, rather than truly international (i.e. having a commercial presence) in other countries. All banks enable their customers to transact internationally, but that does not mean that they have a share in the international banking market. A customer using a debit or credit card abroad does not mean that the 'home' bank has a presence on the banking market wherever the card is used."

- The last sentence of that paragraph epitomises a central issue in this case. On the one hand, there is a natural resistance to the suggestion that every time an individual uses a credit card or presents a cheque for payment in a foreign country, they thereby effect use of the trade mark in that foreign jurisdiction which is sufficient to support a continued trade mark registration by the proprietor. However, looked at from a different perspective, in so far as undertakings accept a relevant payment instrument in the United Kingdom on the strength of its origin with a foreign financial undertaking, it is hard to see an entirely logical reason for why that should not be treated as constituting use of the trade mark in the jurisdiction where the instrument is presented. I asked the parties whether they had identified authorities in which this issue had been considered either by the EU courts or by the appellate tribunals of the EUIPO. I was told that there was no relevant case law dealing with this issue expressly and that it was necessary to resolve the case by reference to general principles, which the hearing officer also did.

CATEGORIES OF ALLEGED USE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

- The hearing officer reminded herself correctly that an evaluation of genuine use for the categories in question involves a global assessment. It includes looking at the evidential picture as a whole, not whether each individual piece of evidence shows use by itself, nor does it assess economic success or scale of use as such.

- The hearing officer then grouped the issues of use as follows:

(i) Advanced payment guarantees;

(ii) Cheques;

(iii) Use on the website;

(iv) Use on credit and debit cards;

(v) A press release about a banking award;

(vi) Details concerning a London Stock Exchange listing.

It is convenient to consider these categories including the allegation that the hearing officer ignored important evidence and then address the general criticisms of the decision.

(i) Advanced payment guarantees

- The hearing officer summarised the evidence relating to advanced payment guarantees as follows:

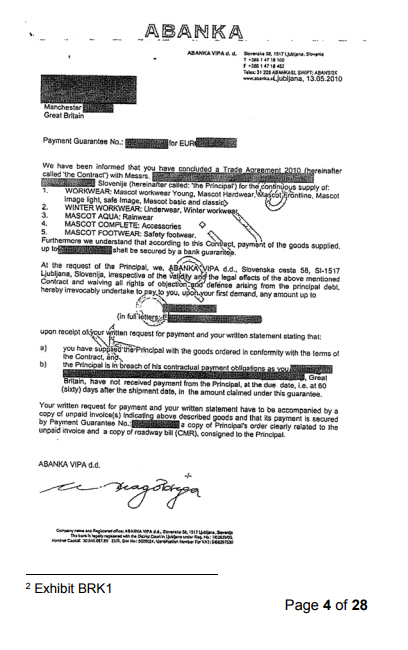

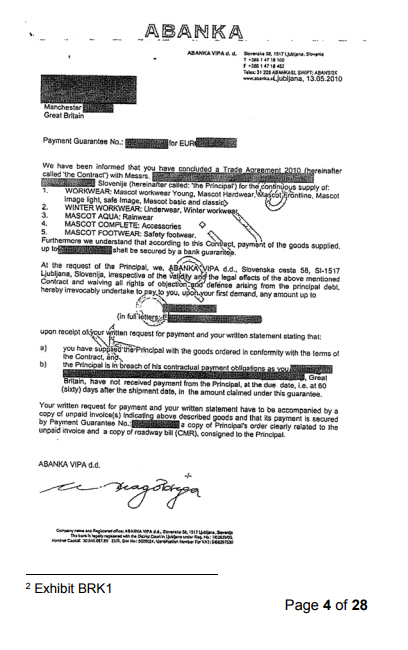

"9. Evidence has been filed by Barbka Krumberger, who is the proprietor's Legal Advisor. Ms Krumberger exhibits2 correspondence with UK-based entities regarding advanced payment guarantees, dated 13 May 2010, 28 December 2010, 20 May 2011, 29 June 2011 and 8 November 2011. An example is shown here:

and later she described it in these terms:

"35. A good illustration of this point is the evidence and submissions relating to the advanced payment guarantees. These are sent by the proprietor in Slovenia to an entity in the UK, reporting that the UK entity has concluded a trade agreement with a party in Slovenia, "the Principal". The first guarantee in Exhibit BR1 states:

"At the request of the Principal, we, ABANKA VIPA d.d., Slovenska cesta 58, SL-1517 Ljubljana, Slovenija .... Hereby irrevocably undertake to pay to you, upon your first demand...".

This shows only that the provision of bank guarantees was a service provided to a banking customer in Slovenia by the proprietor. The service is not provided to the UK entity, which cannot even be termed as an end consumer. The consumer is the bank's customer in Slovenia. Similarly, I agree with Mr Alkin that the cheques are a service provided to a customer of the proprietor in Slovenia; a cheque is made out to a third party in the UK, but there is no meaningful reliance by the third party on the fact that the cheque has ABANKA upon it; there is no guarantee of payment associated with the trade marks. Neither the advanced payment guarantees nor the cheques show that the proprietor has engaged in real commercial exploitation of the marks, as warranted in the UK banking sector to maintain or create a share in the UK banking market".

- The difficulty with this formulation of the test for whether there has been use is that it does not focus specifically on the services in respect of which it is alleged that use has been proved. While it is true that, relative to the wide category of banking services, the provision of a small number of letters of guarantee may be regarded as insignificant - and insufficiently substantial to constitute genuine use over the whole sector of banking services - the Act requires the tribunal to evaluate first what use there has been for any goods or services and then frame an (often much narrower) description to reflect that use.

- Among the very numerous services in respect of which the mark is sought to be maintained is the sub-category "issuing of…guarantees". Abanka submits, first, that, if focus is directed to that sub-category alone, these guarantees show use of the mark not only directed to the UK in general terms but specifically sent to and intended to be relied on by undertakings in the UK.

- Thus, in the example illustrated, Abanka is irrevocably undertaking to pay the undertaking in the UK upon first demand and the guarantee is, in a real sense, "issued" to the undertaking in the UK. Abanka therefore submits that the hearing officer misunderstood and mischaracterised the nature of a guarantee of this kind.

- Abanka submits, next, that this involves the undertaking in the UK relying, inter alia, on the creditworthiness of Abanka in deciding whether to accept that guarantee as well as having ensured that it had been put in appropriate funds by its customer.

- Abanka's argument is, in essence, that the hearing officer failed to appreciate that there could be use of a mark at different points in a financial transaction to more than one undertaking: in the first instance, the mark was used to Abanka's customer in Slovenia who arranged for the guarantee and doubtless paid an arrangement fee for it, directly or indirectly. But, Abanka contends, there was also use of the mark when that customer, having purchased the guarantee then provided it (or asked Abanka to provide it) to the undertaking in the UK which then relied on it in the trade financing transaction in question.

- Abanka contends that it is unreal to treat the principal in Slovenia as a "customer" and thereby seeks to exclude the beneficiary of the guarantee from being the beneficiary of the service. Abanka argues that, if anything, the beneficiary of the guarantee is more of a beneficiary than the notional Slovenian "customer".

- In one sense, Abanka's argument has a certain logic to it. The beneficiary in the United Kingdom is relying on the guarantee and possibly on the fact that it has been provided by Abanka rather than some other financial undertaking. It may, in certain cases, be important to the ultimate beneficiary that such a guarantee is provided by a specific bank (possibly, for example, because that bank is known to be solvent or is known not to quibble about payment on the guarantee upon presentation of conforming documentation). It is a situation in which the guarantee of origin of the guarantee may be significant.

- However, the central point that this argument misses, in my judgment, however it is framed, is that Abanka is providing the guarantee to the customer in Slovenia in exchange for payment. Such a situation is no different to a supplier of goods in Slovenia doing so in the knowledge that such goods may be sent (by the customer for such goods) to the United Kingdom. The fact that such may be known to take place does not mean that Abanka is providing the goods to or in the United Kingdom. In the case of a guarantee, a customer of Abanka may transmit the guarantee to its counterpart trader in the United Kingdom but it does not follow that Abanka has thereby used the mark in the United Kingdom.

- That is a situation in which (in some sense) there is use of the mark Abanka to an undertaking in the United Kingdom this is not, in my judgment, use of the mark ABANKA by Abanka in the United Kingdom. Abanka has not thereby sought to maintain or increase market share for its services in the United Kingdom.

- Although that was not exactly the analysis adopted by the hearing officer, her approach was similar and I do not think it can be faulted on this basis. One of the reasons for requiring proof of use is to ensure that the proprietor of a trade mark has itself done something to justify its retention of exclusive rights in the United Kingdom. In my judgment, this is not a situation in which that occurs as a result of the provision to a client in Slovenia of a payment guarantee in the course of financing a UK-Slovenian transaction.

(ii) Cheques

- In my view, the analysis in respect of cheques is similar to that in respect of guarantees.

- The hearing officer summarised the evidence and reasoning with respect to use on cheques as follows.

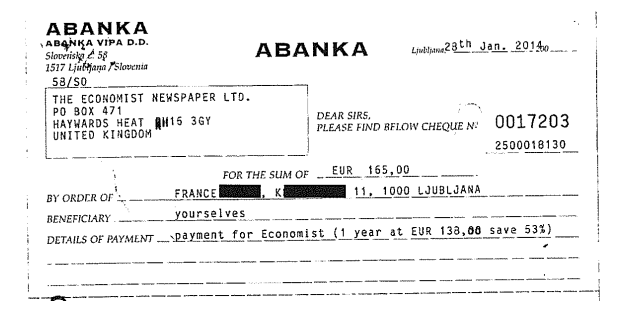

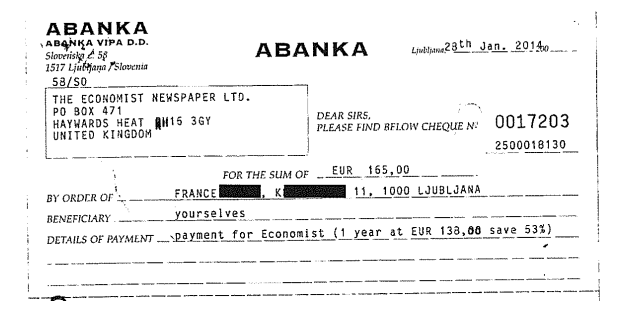

"10. Ms Krumberger states that the proprietor has issued cheques to various entities in the UK in both relevant periods. She states that the cheques are issued based on the order of a Slovenian company or a natural person, and the payment is made from their account with the proprietor to the account of the receiving party. The cheques are then sent to the UK entity, which then cashes the cheque with their own bank. Ms Krumberger states that there were 79 such cheques issued between 2010 and 2014, and two examples are shown in Exhibit BRK2 from the second relevant period. One is shown here:

"

"

and later,

"Similar submissions were made about the cheques. Dr Curley considered that the cheques are relied upon by UK-based entities which accept the cheques and cash them in their own banks, thereby relying upon the ABANKA trade marks as guarantees of origin and therefore of payment. Conversely, Mr Alkin submitted that the cheques are a service provided to a customer of the proprietor in Slovenia; e.g. when a cheque is made out to The Economist (exhibit BRK2). This is not a transaction with the magazine, but, instead, is a service provided to the Slovenian customer so that they can subscribe to the UK magazine. There is no meaningful reliance by The Economist on the fact that the cheque has ABANKA upon it; there is no guarantee of payment associated with the trade marks."

- I am doubtful as to whether it is right to say that there is "no meaningful reliance" by the payee of the cheques on the fact that the cheque has ABANKA upon it. However, the key point is that, as with the payment guarantees, the use of the trade mark by Abanka is in Slovenia to a customer there to whom the service of providing cheques is given. The fact that this cheque may be sent by the customer to an undertaking in the UK in payment for goods or services does not seem to me to constitute use of the mark by ABANKA in the UK for much the same reasons.

- Nor can it credibly said that this is use indirectly by Abanka in the UK even though Abanaka may know that its cheques have been used to pay for goods and services in this country. So in my judgment, the same points apply to cheques as apply to credit cards. Accordingly, I am not satisfied that the hearing officer fell into error in her evaluation on this point.

(iii) Use on the website

- The next kind of use identified is on a web-site which is accessible from the UK and which has parts of its contents in English.

- The hearing officer referred to the decision of Professor Phillip Johnson, sitting as the Appointed Person, in Johnny Rockets (BL O/240/16) E.T.M.R. 37 where, having analysed the Starbucks case, he said at para. [29].

"29. While the test for genuine use is different from that for establishing goodwill for the purposes of passing off, the central principle is the same. If customers buy services in the United Kingdom, which they enjoy outside the United Kingdom, such as hotel services, this is might be use in the United Kingdom. This point seems to have been taken for granted by the Court of Appeal in Thomson Holidays Ltd. v Norwegian Cruise Line Ltd [2002] EWCA Civ 1828 (more recently, see the decision of the registrar in Raffles (O/134/15) which is currently under appeal). Whether a dinner reservation made in the United Kingdom for a restaurant outside the United Kingdom is sufficient to be genuine use is more difficult. I am doubtful, for example, that a customer ringing from her home in London for a reservation at her favourite restaurant in New York would be sufficient in itself. What is clear is that however many thousands of British tourists visit a famous restaurant in New York, sales to those customers will never amount to use in the United Kingdom unless the particular commercial arrangement began in some way when the customer was in the United Kingdom."

- The hearing officer also summarised the effect of the CJEU case law as follows in para [26]:

"26….. In joined Cases C-585/08 and C-144/09, Pammer v Reederei Karl Schlu¨ter GmbH & Co. KG and Hotel Alpenhof GesmbH v Heller, the CJEU interpreted the national court as asking, in essence, "on the basis of what criteria a trader whose activity is presented on its website or on that of an intermediary can be considered to be 'directing' its activity to the Member State of the consumer's domicile ..., and second, whether the fact that those sites can be consulted on the internet is sufficient for that activity to be regarded as such". The court held that it was not sufficient for this purpose that a website was accessible from the consumer's Member State. Rather, "the trader must have manifested its intention to establish commercial relations with consumers from one or more other Member States, including that of the consumer's domicile". In making this assessment national courts had to evaluate "all clear expressions of the intention to solicit the custom of that state's customers". Such a clear expression could include actual mention of the fact that it is offering its services or goods "in one or more Member States designated by name" or payments to "the operator of a search engine in order to facilitate access to the trader's site by consumers domiciled in various member states". Finally, the court concluded:

"The following matters, the list of which is not exhaustive, are capable of constituting evidence from which it may be concluded that the trader's activity is directed to the Member State of the consumer's domicile, namely the international nature of the activity, mention of itineraries from other Member States for going to the place where the trader is established, use of a language or a currency other than the language or currency generally used in the Member State in which the trader is established with the possibility of making and confirming the reservation in that other language, mention of telephone numbers with an international code, outlay of expenditure on an internet referencing service in order to facilitate access to the trader's site or that of its intermediary by consumers domiciled in other Member States, use of a top-level domain name other than that of the Member State in which the trader is established, and mention of an international clientele composed of customers domiciled in various Member States. It is for the national courts to ascertain whether such evidence exists."

- The hearing officer then applied that approach to her evaluation of the evidence of use on the web-site as follows:

"27. The proprietor's evidence shows that it has an English-language version of its website, which includes links to e.g. its personal and corporate banking services. Dr Curley submitted that the evidence shows that the English-language version of the website had been accessed by UK-resident clients of the proprietor using its online banking services. He said that there is no requirement that the users of the website, in the UK, must be UK nationals: it makes no difference whether they are Slovenian, or whether the bank accounts were opened in Slovenia. Mr Alkin agreed that the website is accessible from the UK, but maintained that this is not enough to show genuine use. He submitted that English is the international language of the West and so the mere fact that a section of it is available in English is not evidence that the website is targeted at UK customers. Further, Mr Alkin submitted that the customer opens the account in Slovenia, but then when in the UK remotely accesses the bank's services via the website. Therefore, there is no transaction in the UK: the commercial relationship began in Slovenia."

- Abanka makes several criticisms of the manner in which the hearing officer dealt with the web-site which may be summarised as follows.

- First, it is said that she wrongly ignored evidence concerning regular access to the web-site from the UK said to have been 2600 accesses from the UK in 2013, 5600 in 2014 and 6300 in 2015. I am not satisfied that she did ignore these accesses. She referred to them in the passage above. The hearing officer's decision was based on the fact that the web-site was not targeted at the UK even if it was accessible from (and had been accessed from) the UK. That was, in my view, correct. The fact that a web-site was accessed from the UK was in this context no more significant in proving use in the UK than is proof that people in the UK had telephoned the bank in Slovenia on frequent occasions. The fact that people in the UK are able to and do contact a foreign-based service provider using telecommunication means provided by that service provider for that purpose does not demonstrate that the service provider is targeting the UK or that there has been use of the marks in the UK.

- Second, it is said that the hearing officer misunderstood or misapplied the EU law on web-site targeting and ought to have regarded it as relevant that the web-site had a section in English. I do not think she disregarded this factor. She did not think it was conclusive and in view of the fact that English is an international commercial language, the fact that parts of the web-site were in English does not show that it was particularly (or at all) targeted at the UK.

- The case law on targeting is clear that whether or not a web-site is targeted at the UK involves a multifactorial analysis. Birss J said in the context of a copyright case, Omnibill (Pty) Ltd vEgpsxxx Ltd & Anor [2014] EWHC 3762 (IPEC), at [12]

"It is clear that the question of whether a website is targeted to a particular country is a multi-factorial one which depends on all the circumstances. Those circumstances include things which can be inferred from looking at the content on the website itself and elements arising from the inherent nature of the services offered by the website. These are the kinds of factors listed by the CJEU in Pammer in the passage cited by Arnold J. However as can be seen from paragraph 51 of Arnold J's judgment he took other factors into account too, such as the number of visitors accessing the website from the UK. I agree with Arnold J that these further factors are relevant. Their relevance shows that the question of targeting is not necessarily simply decided by looking at the website itself. Evidence that a substantial proportion of visitors to a website are UK based may not be determinative but it will support a conclusion that the acts of communication to the public undertaken by that website are targeted at the public in the UK."

- The same principles apply here. In my view, the hearing officer was entitled to come to the conclusion she did on the evidence in this case, particularly since there was no reliable material relating to the comparative access of the website from the UK or elsewhere.

- Third, it is said that it was relevant that there was substantial use of the web-site from users in the UK (irrespective of whether they were residents or visitors and irrespective of whether they began their relationship with the proprietor in Slovenia or in the UK). This is the same point as the first one considered above. The hearing officer considered the point but did not think it was decisive. She was right.

- Fourth, it is said that she ought to have taken account of the international nature of the services provided, that it is in the very nature of banking services that they can be conducted online and if people are conducting online banking via the website from the UK, that is not merely accessing the web-site or being exposed to it - it amounts to using the service in the UK. I am unpersuaded by this criticism. Again, it suffers from the problem that in such a case, there could be use even if the undertaking in question is a purely passive recipient in Slovenia of requests from someone in the UK to transfer funds.

- In my view it is also relevant, albeit not conclusive, that Abanka is not authorised by the relevant financial regulator to provide banking services in the United Kingdom. In Stichting BDO, Anrold J treated a similar factor as relevant in deciding whether there had been used in relation to debt collecting services, saying, at [86]:

"Debt collection services (Class 36). The Claimants rely upon evidence that they have used the Trade Mark in relation to insolvency work, and that such work includes collecting debts. The Defendants do not dispute those facts, but dispute that they establish use in relation to "debt collection services" as that expression would be understood by the average consumer. In support of this, the Defendants rely upon the fact that the Claimants are not even members of the Credit Service Association, the body that regulates debt collection. In addition, Mr MacGregor accepted that debt collection was a different industry with which the Claimants did not compete. I agree with the Defendants on this issue, and accordingly this category must be revoked."

- I do not therefore consider that the hearing officer was wrong to reject this allegation of use.

(iv) Credit and debit cards

- The next issue concerns alleged use on credit and debit cards. The hearing officer summarised the key evidence and arguments on this issue as follows:

"28. The credit and debit cards, which bear the trade marks, are used by the proprietor's customers who are resident in the UK. Mr Alkin submitted that the point is the same as for the website; there is no evidence that the customers opened the account from the UK. Dr Curley submitted that the fact that the cards were sent to customers who are resident in the UK is evidence of genuine use in the UK. As with the cheques, they guarantee the origin of the service because the cards bear the trade marks.

29. In relation to the evidence showing use of the cards in the UK, Mr Alkin's position was that the figures given in the evidence about transactions (1,899,968 to the value of 56,800,000 Euros) are not tied to the 80 cards which were issued. There is no evidence showing that the 80 card holders were responsible for all, or any, of these transactions. He interpreted the evidence as showing that the transactions were undertaken by Slovenian customers (i.e. resident in Slovenia) who had travelled to the UK and used the cards whilst in the UK. As support for this contention, Mr Alkin pointed out that 56,800,000 Euros would, otherwise, be a large (and, therefore, unlikely) amount for 80 cardholders to spend."

- Abanka's criticisms under this head fall into two broad categories.

(i) Use of ABANKA credit or debt cards by foreign visitors

- First, that it was not right to disregard the fact that a large volume of transactions, using Abanka credit or debit cards, were conducted including by visitors to the UK using their cards in the UK to purchase goods or services or to obtain cash from ATMs while travelling in the UK. Although it is true that the hearing officer did not specifically have regard to this alleged category of use, I do not think she can be criticised for not doing so. As the hearing officer said at para [34]:

"A customer using a debit or credit card abroad does not mean that the 'home' bank has a presence on the banking market wherever the card is used."

- This is a situation in which there is no use of the trade mark in the UK by the proprietor of the registration but use of cards marked with the trade mark in the UK by customers of the proprietor. That does not constitute use of the mark by the proprietor in the UK.

(ii) Credit and debit card customers in the UK

- Second, Abanka contends that the hearing officer effectively applied too strict a quantitative threshold in considering that the small number of credit and debit card customers resident in the UK did not amount (in effect) to sufficient use to be genuine. These appeared to be customers of Abanka who were resident in the UK who were supplied with credit and debit cards as part of the services associated with their account in Slovenia.

- The difficulty with this contention of use is that it is not possible to tell from the evidence in the case whether these credit or debit cards were supplied to these customers in Slovenia (perhaps to a home address of the customer in Slovenia) and then used by those customers while (additionally) living in the UK. It is quite possible that these debit and credit cards really form part of the suite of domestically provided banking services in Slovenia although their users may have asked for the cards to be sent to the UK while they were living here.

- This situation seems to me rather on the borderline. In the case of a financial services undertaking which is based abroad and which has a significant number of customers in the UK it may in some cases be right to treat the provision of payment cards to them in the UK as the provision of such services in the UK even if incidental to holding a bank account in a foreign country. But I do not consider that the mere presence in the UK of a small number of Slovenian bank account holders who have credit or debit cards bearing the name of that bank constitutes use of the mark by Abanka in the UK in relation to relevant services.

- Here again, although my reasoning is not identical to that employed by the hearing officer, it is similar and I do not consider that her conclusion was wrong.

(v) Press release/advertisement about a banking award

- As the hearing officer recorded one of the exhibits (BRK9) consisted of a press release screenshot, dated 4 December 2009, concerning an award given to Abanka for being Slovenia's Bank of the Year. The award was given by the UK magazine "The Banker" and the award ceremony was held on 3 December 2009, in London.

- The hearing officer was, in my view rightly, unimpressed with this evidence as showing use of the mark in the UK.

- Abanka contends that the fact that The Banker is a UK magazine with significant UK circulation should have regarded as more important and that this was an advertisement/award which would have come to the attention of in international clientele including people in the UK or who attended the award ceremony.

- I do not accept those criticisms. As the press release says, "an important factor in the selection was the listing of the Abanka shares on the Ljubjana Stock Exchange in October 2008 which concluded the project of increasing the bank's equity through the issue of new shares". According to the press release, this increased the bank's capital significantly "which guaranteed the bank's capital stability in uncertain economic conditions". Although there were apparently other contributing factors to this award, it is difficult to see how being the passive recipient of an award which was largely conferred for successfully recapitalising itself in Slovenia and thereby avoiding the worst of the financial crisis assists Abanka in showing use of the mark in the UK, even if that award is given in London and publicised in an English-language banking journal with a significant UK readership (as to which there was no direct evidence).

- Again, this approach to whether or not there was use targeted at the UK is in line with the Stichting BDO case. In that case, Arnold J made fine distinctions between magazine advertisments which were directed at a general or global audience and those which were genuinely targeting the UK (see, for example, the discussion at [119]-[139], which included evaluation of advertisments placed in The Banker which were not necessarily treated as targeting the EU, let alone the United Kingdom).

(vii) London Stock Exchange listing of Eurobonds in 2009

- The final category of alleged use relates to the issue of floating rate notes and other similar securities admitted for trading on the London Stock Exchange in 2009.

- The evidence shows that Abanka applied for the admission of these securities to trading on London Stock Exchange Form 1, with a view to the application being considered in September 2009. The application was for certain securities to be admitted to the main market for the purpose of a MTN (medium term note) programme for the issuance of debt instruments. The application was made for €500,000,000 Floating Rate Notes due 2012, guaranteed by the Republic of Slovenia. The brief description of the business in the application was "Slovenian bank issuing Notes backed by the Government of Slovenia". Abanka declared that it was or would be in compliance with the relevant UK regulatory standards (see BRK 10).

- In addition to the application for admission of the securities, the evidence showed that an Information Memorandum was issued at about the same time giving details of the issue of the Notes, including particulars of the interest rate payable, the interest payment date. It stated that the Notes had been admitted to the Official List and admitted to trading on the London Stock Exchange's Regulated Market, that they would be issued in the denomination of €50,000 and integral multiples of €1000 in excess thereof and gave details of their anticipated credit rating by Moody's and Fitch. The Memorandum drew attention to the various risks involved in purchasing the Notes relating to the characteristics of the issuer, Abanka, and the Notes themselves.

- The evidence regarding this issue is, however, thin and amounts to a single paragraph in the first witness statement of Barbka Rus Krumberger, a Legal Advisor at Abanka and supplementary evidence in her second witness statement that Abanka does not have detailed information of the ultimate purchasers following their listing because that information is only held by intermediary banks. However, she says that three UK-based financial institutions took part in the purchase of those bonds with a total investment amounting to 1.1 million Euros. She says that, based on her experience and discussions with colleagues, many UK-based financial services personnel would have seen the issue documents (including those who saw them and decided not to invest). There is no issue that these securities used the mark ABANKA to identify the borrower (and undertaking that would repay the principal and interest).

- The hearing officer described this aspect of the case in the following terms at para. [34]

"The flotation on the London Stock Exchange was to raise funds for the proprietor itself. The final page of the memorandum states that the proprietor derives its information for the memorandum from the Republic of Slovenia, the Slovenian banking market and its competitors."

- Abanka criticises this part of the decision for the following reasons. First, it is said that it ignores the important distinction between the requirements for use in the law of trade marks and the law of passing off and that, for the former, use in advertising may suffice. Second, that the hearing officer's decision did not take sufficient account of the actual customers for these bonds referred to above.

- In my judgment, there is substance in Abanka's criticisms of the hearing officer's evaluation under this head.

- The hearing officer appears to have based her decision largely on the fact that the purpose of the issue of securities of this kind was to raise funds for Abanka itself. I am not convinced that this is or should be the decisive factor in this case. In a conventional case, where an undertaking is straightforwardly selling goods which it has created on the domestic market in exchange for payment, it may equally be said that it is thereby also trying to raise funds for itself but that would not, of itself, preclude a finding of genuine trade mark use by that undertaking in respect of those goods. Similar considerations apply with the sale of bonds. In such a case, the person selling the bond is of course, in some sense, simply borrowing money but it is in my view natural to view such bonds as objects of commerce which are both advertised and sold in a particular location. That is notwithstanding the fact that a bond may be categoried as a chose in action and there is no natural category of services into which such would fit. In this case, the marketplace chosen was the London Stock Exchange, i.e. the UK. The characteristics of the issuer of the bond, including its reputation for creditworthiness are clearly important to a purchaser and were described in the promotional material.

- In my view, the use of the mark ABANKA in relation to such bonds sold in the United Kingdom was use of the mark in this country. It is hard to say that it was insignificant since over £1 million worth were purchased by UK based institutions. Although, by the scale of the bond market as a whole, that is very modest and this was a small proportion of the total issue, actual sales combined with the marketing of them seems to me to satisfy the test of being genuine use, directed to establishing or maintaining a market in the securities in question. There is no sense in which this was token merely to preserve the trade mark. Indeed, it would be surprising if preservation of the trade mark was on anyone's mind in issuing this bond.

- The respondent contends that the hearing officer was right and that issuing bonds does not involve provision of a service and there are no customers for such services. As indicated above, I think that is too narrow an analysis. Most people in the financial services community (and probably more generally) would regard themselves as having bought something when purchasing a bond even if it is "merely" the purchase of a right to repayment of the sum lent with interest. It is true that it may be possible to have a debate about whether this constitutes a "service" at all (an argument of a kind perhaps similar to that over retail services in the past – see above on the subject matter of trade here being a chose in action) but I do not consider that trade mark law takes such a narrow view. No argument based on case law or principle was advanced for why it should. I am not persuaded by the point that says that simply because a customer for a bond is merely lending the issuer money and the issuer is merely agreeing to repay with interest, that no service is provided by the issuer of the bond in exchange. The respondent accepts that, in principle, an undertaking which is offering bond issuing services (by which I understand it to mean those actually managing the issue) would be entitled to maintain a registration. It is not clear why a person actually issuing the bond would not be entitled to do so.