Mr Justice Birss :

|

Topic

|

Paragraphs

|

|

Introduction

|

1

|

|

The witnesses

|

8

|

|

The skilled team and the common general knowledge

|

32

|

|

The lacosamide patent

|

42

|

|

Priority

|

53

|

|

Assessment – priority

|

79

|

|

The evidence

|

86

|

|

Inferences

|

107

|

|

Obviousness

|

125

|

|

Le Gall

|

126

|

|

What to do with Le Gall

|

146

|

|

Bardel

|

209

|

|

Conclusion

|

212

|

Introduction

1.

This is a patent action. It relates to EP (UK) 0 888 289. The patent covers

an anti-epileptic drug called lacosamide. The lacosamide compound is (R)

-N-benzyl-2-acetoamido-3-methoxypropionamide. Lacosamide is a successful

medicine, with annual worldwide sales projected for next year to reach €1

billion. The patent application was filed on 17th March 1997

claiming priority from a US filing on 15th March 1996. The patent

expired on 18th March 2017. There is a supplementary protection

certificate (SPC/GB09/007) which means that protection for lacosamide in this

jurisdiction continues until 2022.

2.

The claimant (Accord) is a generic pharmaceutical company. It contends

that the patent is invalid. If it is right then the SPC will be revoked,

clearing the way for generic competition. The defendant (RCT) is a technology

investment and management company based in the USA. In effect the defendant

works as a technology transfer office for a number of universities. This case

concerns work done at the University of Houston by Professor Harold Kohn and

his group. Prof Kohn and his group had been working on anticonvulsant

compounds since the 1980s. The patent came out of that work. It is

exclusively licensed to the pharmaceutical company UCB, who sell lacosamide to

treat epilepsy under the brand name VIMPAT. A share of the licence fees paid

to RCT under the licence goes back to the university and to Prof Kohn and the

other relevant workers in the group.

3.

Accord contend the patent is invalid on two grounds. Accord challenges

the patentee’s legal entitlement to claim priority from the 1996 priority

document. If that challenge is successful then a paper by Choi becomes

relevant prior art since it was published after the priority date but before

the filing date. That paper makes lacosamide available to the public and there

is no dispute that if priority is lost, the patent is invalid.

4.

Accord’s second challenge is obviousness. This is based on the state of

the art before the priority date, which included a number of papers and other

publications from Prof Kohn’s group relating to their work on anticonvulsant

compounds. Accord relies on two starting points for the obviousness analysis.

One is a master’s thesis by a student called Philipe Le Gall. It is entitled 2-Substituted-2-acetamido-N-benzylacetamides

Synthesis. Spectroscopic and Anticonvulsant Properties. It was made

available to the public in December 1987. Le Gall was a student of Prof Kohn.

The other attack is based on a paper referred to as “Bardel” the full citation

of which is given below. That also came from the work of Prof Kohn’s group.

5.

The attack based on Le Gall was originally put in two ways but by the

closing Accord had narrowed its case over Le Gall to a single approach. Accord

submits that it would be obvious for the skilled team given Le Gall at the

priority date in 1996 to do a literature search to find what had come out of

Prof Kohn’s group in the nine years since the thesis. They would find a number

of publications from the group. Accord contends that lacosamide is obvious

over Le Gall taking that supplementary information into account. The other

approach to Le Gall which had been part of Accord’s case until closing was to

rely on the thesis alone and not the supplementary information. That case was

abandoned.

6.

RCT denies the allegation of lack of entitlement to priority and denies

that the invention is obvious.

7.

There had been further points or squeezes on insufficiency and

substantive priority concerning chronic toxicity but by the closing it was

common ground they did not need to be addressed.

The witnesses

8.

Accord called two technical experts: Professor Brian Cox, a medicinal

chemist and Mr Reece Jones, a toxicologist.

9.

Professor Cox is Professor of Pharmaceutical Chemistry at the School

of Life Sciences, University of Sussex. Professor Cox received his PhD at the University of Manchester in 1986. He then had extensive experience in industry first at

Schering-Plough and then at Glaxo Research Group from 1990. Whilst at Glaxo

Research Group, Professor Cox worked on various of their medicinal chemistry

programs, and was promoted to Research Leader in 1995. One of his projects

was a study starting in September 1995 to look for analogues of the

anticonvulsant sodium-channel blocker lamotrigine, seeking a treatment with

improved tolerability. Around the same time, he was also lead chemist on a

project to identify the molecular target of a competitor anticonvulsant

product, retigabine and also worked on a project concerning calcium channel

agonists as potential anticonvulsants. His Professorship at the University of Sussex started in 2014.

10.

RCT levelled a number of criticisms of Professor Cox. The major ones

were that: his positions were at odds with the textbooks, his views were

influenced by hindsight, and he gave long answers which did not answer the

questions put. I reject all of RCT’s criticisms, for the following reasons.

Professor Cox did not accept certain points in textbooks but that was an

expression of his genuine views which he explained clearly. On hindsight, I do

not accept Accord’s case that Professor Cox’s opinions on what is obvious over

the prior art were fully formed without any reference to the patent. If it

matters (and I believe it does not) the evidence did not establish that.

However I also reject RCT’s corollary that at some overall level the fact that

his views were formed after he had read the patent means they are necessarily

tainted with hindsight. Professor Cox understood that the court’s task in

trying an obviousness case is to work out what would be obvious, without

hindsight. He sought to help the court by explaining his opinions about that.

As for long answers not answering the question, Professor Cox did give quite

long answers but that was borne of his desire to ensure that the court

understood his full opinions on the topic. Also it was not helped by occasions

on which a question was put by presenting a summary of what the Professor’s

report was said to say but which missed out relevant details.

11.

Professor Cox was a good witness, seeking to help the court resolve the

issues in this case.

12.

Mr Reece-Jones is a consultant toxicologist who trained as a

toxicologist following receiving his HND in Applied Biology from Manchester

Polytechnic. He started training at Hazleton in 1979, and he has worked both

in-house in industry and at consulting toxicology companies. He worked as a study

director since 1988. He has worked on a wide variety of compounds antibiotics,

antihistamines, and central nervous system (CNS) compounds. He is a highly

experienced toxicologist and was well placed to give evidence as to toxicology

in 1996.

13.

Mr Reece-Jones was barely cross-examined. By closing the point to which

his evidence went had been dropped. I thank him for his attendance at court.

14.

RCT called two technical experts: Professor Wolfgang Löscher, a

pharmacologist and Professor Simon Ward, a medicinal chemist.

15.

Professor Löscher is Professor and Director of Pharmacology, Toxicology

and Pharmacy at the University of Veterinary Medicine, Hannover. He is also the

founder of the Centre of Systemic Neurosciences there. He has worked in the

field of anticonvulsant drugs since the 1970s. He has worked primarily as an academic

but his work has always involved close links with industry and drug

development.

16.

Accord submitted that Professor Löscher’s experience with drug

development was primarily as a consultant brought in only when the drugs were

already at a stage of pre-clinical development or later. The contrast was

between that and experience of an earlier stage of drug development. Part of

Professor Löscher’s extensive work in this field did involve the tasks referred

to by Accord, but I reject the submission that this qualifies his expertise.

He knew very well how the in vivo pharmacological assays such as the MES

test (see below) were used in early stage drug development and was well

qualified to express opinions about all the issues he covered in this case.

17.

Accord submitted he was an ardent advocate of criticism of the MES test

in particular especially for its tendency, as he saw it, to produce “me too”

drugs. So he was. I was not satisfied that this view of the MES test

represented the common general knowledge at the relevant time. He also had

strong views about the need to address drug resistant epilepsy in particular as

opposed to treating epilepsy in general and again I am not persuaded those

views represented the common general knowledge of a drug development team in

1996. He also had worked with and visited the NIH and had personal knowledge

about the results of a comprehensive programme of testing putative

anticonvulsant compounds for drug developers which the NIH had been running for

a number of years by 1996. I will deal with that in context if need be.

18.

Professor Löscher was an excellent witness, seeking to help the court at

all times.

19.

Professor Ward is Visiting Professor of Medicinal Chemistry in the

School of Life Sciences at the University of Sussex and is also Sêr Cymru

Professor in Translational Drug Discovery and Director of Medicines Discovery

Institute at Cardiff University. After graduating in chemistry in 1993

Professor Ward worked at the pharmaceutical company Chiroscience for a year and

then went back to Cambridge to do his PhD (1994-1997). He then worked at the

pharmaceutical company Cerebrus until moving to Knoll in 1999 and on to GSK in

2001 where he remained until taking up his Professorship at the University of

Sussex.

20.

Professor Ward was another good witness, seeking to help the court.

21.

At the priority date (1996) Professor Ward was studying for his PhD.

Accord submitted he was not in a position to assist the court about the

attitudes, interests and common general knowledge of those in the field at the

relevant date. Accord submitted his evidence about this could not be relied

on. I do not accept the full extent of that submission. I distinguish between

two different things. In my judgment Professor Ward was able and was well

qualified to assist the court in relation to medicinal chemistry itself, in

other words the way medicinal chemists apply their chemical knowledge and skill

to the problems presented by pharmaceutical drug development. He is an expert

medicinal chemist and was close enough to the field at the time to be able to

assist the court. He was good at explaining things. Medicinal chemistry as a

discipline did not change over the relevant period in a manner which would

undermine Professor Ward’s ability to assist. The fact he did not work on

anticonvulsant or CNS drugs until much later does not matter. Medicinal

chemists would routinely be called upon to work in a new field. Despite hints

to the contrary by Accord, I find that Professor Ward’s work since he graduated

in 1993 has all been in or closely related to medicinal chemistry, with some

synthetic chemistry as many medicinal chemists would also undertake

particularly at the start of their careers.

22.

However where the nature and timing of Professor Ward’s personal

experience is relevant and does qualify his ability to help is in addressing

evidence about the general approaches of drug development teams in

anticonvulsant medicine in 1996. He was not there.

23.

The parties also called experts on US federal and state law. They were

not cross-examined.

24.

Accord relied on Professor Robert Merges for US federal law; and Judge

Leonard Davis for the law of the state of Texas.

25.

Professor Merges is the Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati Professor

of Law and Technology at US Berkeley School of Law, a position he has held

since 1995. He teaches Intellectual Property, Patent Law and Contracts and his

research focusses on the economic aspects of intellectual property rights, with

a focus on patents.

26.

Judge Davis was the Chief Judge of the United States District Court for

the Eastern District of Texas. That court is famous for its experience of

patent law. From 2002-2015 Judge Davis managed one of the busiest dockets in

the United States handling over 1700 patent cases a year, and personally tried as

many as eleven jury trials in one year. The judge was also the Chief Judge of

the Twelfth Court of Appeals of the State of Texas. He has now retired from

the bench and works as Of Counsel at the law firm Fish & Richardson.

27.

RCT’s US law experts are: Professor Donald Chisum on US federal law and Judge

David Folsom on Texas state law.

28.

Professor Chisum has held various professorships at Stanford University,

the University of Washington and Santa Clara University, each of which being

Professor of Law. He is the author of Chisum on Patents, the well known text

book on US patent law.

29.

Judge Folsom is currently a partner in the law firm Jackson Walker LLP.

From 1995 till 2012 he served as a United States District Court Judge, Eastern

District of Texas (as Chief Judge from 2009-2012). During this time he heard

over 250 trials and has presided over hundreds of patent cases.

30.

Rightly, neither side suggested the US law experts were not qualified to

give the evidence they did.

31.

RCT also called a number of fact witnesses, who were not

cross-examined. Their evidence related to the entitlement to priority issue.

The witnesses were Professor Kohn himself, Dr Ramanan Krishnamoorti of the University

of Houston and Mr Timothy Reckart formerly of RCT.

The skilled team

and the common general knowledge

32.

In this case the person skilled in the art is a team. The team will

include a medicinal chemist and a pharmacologist as well as other disciplines.

33.

The only aspect of chemistry worth mentioning at this stage is

chirality. Many of the compounds in this case are chiral. Chiral compounds

exist in two non-superimposable mirror image forms known as enantiomers. The

compounds have a carbon atom with four bonds in a tetrahedral shape and

different substituents attached to each of the four bonds. Chirality is common

in biological systems and in many cases one enantiomer may have a completely

different effect from another enantiomer. A racemate is an equal mixture of

the two enantiomers.

34.

Turning to clinical issues, the skilled team would know that epilepsies

can be categorised by reference to the types of seizure that the patient

suffers from. These can be broadly classed as partial or generalised seizures.

The former arise in a localised area of the brain and are further classified

as: “simple” (where consciousness is maintained); “complex” (where

consciousness is lost or impaired); and “secondarily generalised” (involving

convulsions). Generalised seizures arise in all or large parts of both

cerebral hemispheres and comprise two main categories: “tonic-clonic”/“grand

mal” (involving widespread convulsive activity); and “absence”/”petit mal”

(where consciousness is impaired with little or no motor disturbance).

35.

The treatment of epilepsy involves the administration of an

anticonvulsant drug or cocktail of drugs. These are given chronically, with a

view to preventing or reducing the incidence of seizures.

36.

Various anticonvulsant drugs had been identified by the Priority Date

including the “first generation” anticonvulsants phenytoin, phenobarbital and

ethosuximide which had been discovered in the 1930s/1940s using animal models.

Phenytoin remained a mainstay of the treatment of epilepsy at the priority

date. Various other drugs were discovered in the “second generation” of

anti-epileptic drugs, in the 1950’s and 60’s, including carbamazepine, sodium

valproate and benzodiazepines. These too were found using animal models.

37.

In the early 1990s, a number of new anticonvulsant drugs came on the

market including vigabatrin, gabapentin, lamotrigine, clobazam, topiramate,

felbamate, tiagabine, oxcarbazepine, zonisamide and progabide. Nevertheless,

for the skilled team there remained a need for new and better anticonvulsants

at the priority date.

38.

To a pharmacologist interested in anticonvulsant drugs, there were

various assays based on animal models which could be performed to evaluate the

possible activity of candidate compounds. One was the MES test. MES stands

for Maximum ElectroShock. It was a test in mice or rats in which a seizure is

induced using a standardised electric shock, and the ability of a compound to

prevent the seizure is measured. The effect of the drug is measured at a time

after delivery called TPE (time of peak effect). The seizure is determined by

HLE (hind limb extension) in the test animal. For a compound which is

effective, the MES test produces an ED50 value. That is the dose in mg/kg

require to protect 50% of the animals challenged. So a low ED50 is more

desirable as it represents a higher potency.

39.

Other kinds of assay used involved a chemically induced seizure instead

of a seizure induced by an electric shock. An example is the sc Met test. The

term sc Met refers to the subcutaneous (sc) administration of the compound

Metrazol (pentylenetetrazol). That compound induces the seizures. The test is

not the same as the MES test but it still produces an ED50 value. Other

similar tests using a chemically induced seizure are the sc Bic and sc Pic

tests. These use different compounds to induce seizures.

40.

A different kind of animal test which was also routine was to see if the

compound caused undesirable neurological symptoms. Put simply the point is

that one may be able to treat seizures by giving a drug which acts as a

sedative to the patient; however what is wanted is a drug which can treat the

seizures without a major sedative effect. The possible sedative effect is

assessed using these tests. One of them was the rotarod test, in which rodents

which are trained to balance upon a rotating rod, are given the drug, and the

unwanted neurotoxicity assessed by monitoring the extent to which the animal

can stay on the rod. The other major test used was the horizontal screen test,

in which the animals are placed upon a wire mesh that is slowly rotated 180o.

If the animals are unable to climb to the top of the screen in a certain period

of time, this also demonstrates neurological impairment. Using these kinds of

neurotoxicity tests it is possible to calculate the toxic dose which causes

neurological impairment. This is calculated as a TD50 value.

41.

The ratio of a compound’s ED50 value to its TD50 value is known as its

protective index (PI). The skilled team would want a compound with a good

protective index, to reduce the neurological toxicity issues with the compound

– this was a key selection criterion.

42.

The skilled team looking for promising new anticonvulsant compounds

would gauge the putative compound’s test results (ED50, TD50 and PI) in animal

models such as the MES test against the results for known compounds, such as

phenytoin. If the results were promising the team would screen good compounds

in further animal models such as sc Met. Over time the ED50 levels in the MES

test which a team would consider worth pursuing were dropping. Recognising

that it is an over simplification to pick a value and state that the team would

focus on that, nevertheless by 1996 a fair picture is presented by considering

a team looking for ED50 values in the MES test of around 10 mg/kg or less along

with a good PI.

The lacosamide

patent

43.

The patent starts with a statement that the invention relates to novel

enantiomeric compounds and pharmaceutical compositions useful for treating

epilepsy and other CNS disorders. The background section describes the use of

anticonvulsant drugs to treat seizures, and summarises the two main kinds of

seizures. Various existing drugs such as phenytoin and phenacemide are

mentioned and there is a reference to a prior patent from the Kohn group. At

paragraph [0006] the patent refers to problems with the existing agents

including poor management of the disease and disturbing side effects. A

particular point is made about the difficulty that these agents are

administered chronically and this is associated with liver toxicity. In

paragraph [0007] four criteria for an ideal anticonvulsant drug are set out:

“(1) has a high anticonvulsant activity, (expressed as a low

ED50);

(2) has minimal neurological toxicity, (as expressed by the

median toxic dose (TD50)), relative to its

potency;

(3) has a maximum protective index (sometimes known as

selectivity or margin of safety), which measures the relationship between the

doses of a drug required to produce undesired and desired effects, and is

measured as the ratio between the median toxic dose and the median effective

dose (TD50/ED50);

and

(4) is relatively safe as measured by the median lethal dose

(LD50) relative to its potency and is

non-toxic to the animal that is being treated, e.g., it exhibits minimal

adverse effects on the remainder of the treated animal, its organs, blood, its

bodily functions, etc. even at high concentrations, especially during long term

chronic administration of the drug. Thus, for example, it exhibits minimal,

i.e., little or no liver toxicity.”

44.

The paragraph continues by explaining why, although not so critical for

short term administration, the fourth criterion is extremely important for an

anticonvulsant which is to be taken over a long period of time or in high

dosage as follows:

“It may be the most important factor in determining which

anti-convulsant to administer to a patient, especially if chronic dosing is

required. Thus, an anti-convulsant agent which has a high anti-convulsant

activity, has minimal neurological toxicity and maximal P.I. (protective index)

may unfortunately exhibit such toxicites which appear upon repeated high levels

of administration. In such an event, acute dosing of the drug may be

considered, but it would not be used in a treatment regime which requires

chronic administration of the anti-convulsant. In fact, if an anti-convulsant

is required for repeated dosing in a long term treatment regime, a physician

may prescribe an anti-convulsant that may have weaker activity relative to a

second anti-convulsant, if it exhibits relatively low toxicity to the animal.

An anti-convulsant agent which meets all four criteria is very rare.”

45.

Next is a summary of the invention section which corresponds to claim

1. Although the patent is drafted on the basis of a class of compounds defined

in claim 1, the extent of the class in claim 1 does not matter because claims 8

to 10 relate to lacosamide specifically. The remainder of the summary of the

invention section states that administering the compounds of the invention

provide an excellent regime for the treatment of epilepsy and some other CNS

disorders.

46.

The detailed description section starts with the general synthesis of

the compounds. The synthesis described at Scheme 1 starts from the amino acid

D serine and preserves the chirality of the starting material. A racemic

serine can be used instead and the final product resolved to produce the

relevant R isomer (paragraph [0030]). Wide general statements are made about

dosing, route of administration, dosage forms and excipients (paragraphs [0031]

– [0042]).

47.

The examples start at paragraph [0044]. Examples 1, 2 and 5 provide

alternative syntheses for lacosamide. Examples 3 and 4 relate to other

compounds in the class of claim 1 (they are fluorinated). Comparative examples

1 – 13 relate to other similar compounds which are not within the claimed

class.

48.

Pharmacology is dealt with from paragraph [0077] and the results of

various animal studies are in Table 1. They show testing of lacosamide and two

other compounds within the claimed class along with a number of comparative

example compounds. The tests are in mice (ip) and rats (po). The tests are

MES and neurological toxicity via the rotarod test. The results report ED50

and TD50 values with some 95% confidence intervals. PI values are

stated. The values for lacosamide are:

|

Compound

|

mouse (ip)

|

Rat (po)

|

|

MES

ED50

|

Tox

TD50

|

PI

|

MES

ED50

|

Tox

TD50

|

PI

|

|

Lacosamide

|

4.5

(3.7-5.5)

|

26.8

(25.5-28.0)

|

6.0

|

3.9

(2.6-6.2)

|

>500

|

>128.2

|

49.

The patent summarises the data in Table I as a whole from paragraph

[0079]-[0085] as showing that the R enantiomers of the invention have quite

potent anticonvulsant activity and an excellent drug profile while the

comparative compounds tested (save for the furyl derivative) are significantly

inferior drugs. Even if the level of neurotoxicity is low and the PI is

satisfactory, the patent explains that one wants to administer as little drug

as possible and so a low potency value is advantageous (paragraph [0085]).

50.

Turning to chronic liver toxicity, in paragraphs [0086]-[0087] the

patent explains that while both the furyl derivative and the compounds of the

invention have a good drug profile, the furyl compound is more toxic to the

animal, making it less suitable for chronic administration. The compound

called BAMP (which is lacosamide) exhibited little if any toxicity to the

animal. The animal toxicity tests on lacosamide are reported in [0089] to

[0105]. There is a short term, 48 hour, study in rats in which minimal liver

toxicity was shown. Then a longer term, 30 day, study in rats was run, which

showed no histological evidence of an adverse effect at the highest doses.

Toxicity studies are run on other compounds outside the invention. The results

for those compounds and for BAMP/lacosamide are summarised in Table 6. The

comparison favours BAMP/lacosamide.

51.

The description ends at paragraph [0141] with a statement that the

compounds of the invention have an excellent drug profile, meet all the four characteristics

outlined before and can be used for chronic administration.

52.

Claim 8 is a claim to lacosamide itself, in other words (R) -N-Benzyl

2-Acetoamido-3-methoxypropionamide. Claim 9 is to the “substantially

enantiopure” compound of claim 8. Claim 10, as dependent on claim 9, is to the

therapeutic composition of an anticonvulsant effective amount of substantially

enantiopure lacosamide and a pharmaceutically acceptable carrier.

Priority

53.

The right to claim priority is in section 5 of the Patents Act 1977.

That section is one of the sections to which section 130(7) applies and so it

is intended to have the same effect as the relevant parts of the EPC. In the

EPC priority is governed by Art 87. This in turn gives effect to Article 8 of

the PCT which in turn gives effect to Article 4(A)(1) of the Paris Convention.

The Paris Convention is the origin of the international priority right.

54.

Before getting into the law any further it is convenient to state the

problem which arises in this case. The underlying facts are not in dispute.

55.

For lacosamide the inventor was Prof Kohn. The US filing from which

priority was claimed was made by Prof Kohn on 15th March 1996. The

international application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) filing

number PCT/US97/04579, which matured into the patent in suit, was filed by RCT

on 17th March 1997 claiming priority from that earlier filing.

There is on the face of it a properly executed written assignment of the

invention from Prof Kohn in favour of RCT dated 4th February 1997.

The assignment expressly includes the right to claim priority at clause 5. In

the context of priority it is convenient to refer to the relevant invention as

lacosamide rather than refer to the whole subject matter of the patent in suit

but nothing turns on that difference.

56.

So is everything in order? Accord say it is not. Accord took a wide

range of points prior to the trial but by the opening its case came down to a

single point. Accord contends that the assignment of 4th February

1997 only took effect as an assignment of the bare legal title to the invention

and priority claim. What it did not do was assign the equitable or beneficial

title to that property to RCT. That equitable or beneficial title was with the

University of Houston (“Houston”). It may (or may not) have ended up with RCT

later but that does not matter. Accord submits that as a matter of law, what

is required for the priority claim to be accepted in this court at this trial

is that the substantive right to priority, also known as the equitable or

beneficial title to that right, was with the correct party on the correct day.

The correct party was RCT and the correct day was 17th March 1997

when the international application was filed. Accord contends that this did

not happen and so the claim to priority should fail.

57.

The reason the substantive right to priority might have been in the

wrong place at the wrong time (if it was) is as follows. The first step is

that for inventions made by faculty members or other university staff such as

associates and employees at Houston, those individuals are obliged as a result

of the contractual arrangements between them and the university to assign them

to Houston (or to a person appointed by Houston such as RCT). That applies to

all the relevant individuals here such as Prof Kohn and the others. This is

common ground.

58.

The second step is that Houston had a long standing agreement with RCT

relating to inventions and patents. It started as an agreement in 1966 between

Houston and RCT’s predecessor. This is also common ground.

59.

By that agreement Houston had the right but not the obligation to offer

inventions to RCT. For any relevant invention made by its faculty/staff,

Houston would make a decision whether or not to offer that invention to RCT.

As between Houston and RCT it did not matter what internal Houston process was

used to make that decision. What matters is that at all relevant times under

the contract between Houston and RCT, Houston was not obliged to offer

inventions to RCT. From RCT’s point of view it was a decision in Houston’s

discretion. Conversely once Houston had disclosed and offered an invention to

RCT, RCT was not obliged to accept it, RCT could choose to accept it or not.

Again how the party (now RCT) made the decision was up to that party (RCT). If

RCT decided to accept the invention it would notify Houston of that

acceptance.

60.

From now on pursuant to the contract, RCT would file and prosecute

patent applications to protect the invention in its own name and Houston would

ensure it could do so and execute or have executed all necessary assignments.

A share of any revenue would be passed back to Houston. In fact under the

arrangement some payments of modest sums such as $3,000 at one early stage

would be made by RCT to Houston. Note that the disclosure and offering were

all confidential so none of this makes anything available to the public and

references to disclosure in this context have to be understood that way.

61.

There was clear evidence of this arrangement working as described for

some work by the Kohn group prior to lacosamide. The project was called “FAA”

which means Functionalised Amino Acid. Compounds would be identified and

tested by Prof Kohn and his group. For this purpose a group of related

compounds is an invention. Houston would consider whether to offer that

invention to RCT. In fact it did decide to do so on a number of occasions.

RCT would take the invention disclosure documents and consider them in order to

decide whether to accept them. RCT in fact did decide to accept them and file

patent applications. The compounds developed by Prof Kohn (not lacosamide)

were licensed to Eli Lilly by RCT as licensor under these patent applications.

The Lilly licence had come to an end before lacosamide.

62.

The problem, says Accord, is that there is no evidence the proper

process took place for lacosamide. There is no evidence of a disclosure by

Prof Kohn to Houston of this invention in order for Houston to make its

choice. Nor is there evidence of Houston, rather than Prof Kohn, offering the

invention to RCT having decided to do so. So, says Accord, what seems to have

happened is the following.

63.

Prof Kohn made the invention. At that stage Prof Kohn was obliged by

his obligations to the university to assign it to Houston or to their order.

So analytically (says Accord) while Prof Kohn held the legal title, Houston

held the equitable title since they had a legally enforceable right to call for

an assignment of the legal title. Accord says this analysis is correct under

US law (Federal and Texas state law). In fact Prof Kohn disclosed the

invention to RCT and RCT did apply for patents. Prof Kohn also did execute the

assignment mentioned already before the international PCT application was

filed. But, says Accord, at the point in time before Prof Kohn signed the

assignment to RCT, the equitable title was with Houston. The written

assignment was not effective to move the equitable title from Houston to RCT

and so the priority claim fails.

64.

Accord’s case rests on two points: first the legal requirements to

establish a priority right and second the factual question of what actually

happened in Texas in 1996/97 and what are the legal consequences in terms of

legal and equitable ownership of property.

65.

In order to address the first point it is necessary to understand where

English law on entitlement to priority has got to. In Edwards

Lifesciences v Cook Biotech [2009] EWHC 1304 (Pat) Kitchin J held

as follows:

“In my judgment the effect of Article 4 of the Paris

Convention and section 5 of the Act is clear. A person who files a patent

application for an invention is afforded the privilege of claiming priority

only if he himself filed the earlier application from which priority is claimed

or if he is the successor in title to the person who filed that earlier

application. If he is neither the person who filed the earlier application nor

his successor in title then he is denied the privilege. Moreover, his

position is not improved if he subsequently acquires title to the invention. It

remains the case that he was not entitled to the privilege when he filed the

later application and made his claim. Any other interpretation would introduce

uncertainty and the risk of unfairness to third parties.”

(my emphasis)

66.

In the large majority of cases, including this one, a patent applicant

starts the process of obtaining a patent by filing a patent application in

their home state (e.g. here the USA). Then a year later an international

application is filed under the PCT designating all states and claiming priority

from that earlier regular national filing. The real importance of this passage

from Edwards v Cook is in the sentence emphasised. In the

normal case described its effect is that the applicant’s title to the priority

claim must be in place by the time the international application is filed. That

is because it is that application which makes the priority claim, claiming as

the priority date the filing date of the earlier application. If the

applicant’s entitlement to priority has not been secured by that time then the

position cannot be fixed after the event. This is a critical aspect of

Accord’s case. The fact that the university and RCT today are making common

cause does not help. Perhaps (and this is pure speculation) that common cause

is the result of some accommodation reached after 17th March 1997

and therefore too late to save the priority claim.

67.

Edwards v Cook has been followed and applied at

first instance on a number of occasions including at least the following:

Arnold J in KCI Licensing v Smith & Nephew [2010] EWHC 1487 (Pat) and Idenix v Gilead [2014] EWHC 3916 (Pat),

Henry Carr J in Fujifilm v Abbvie [2017] EWHC 395 (Pat);

and me in HTC v Gemalto [2013] EWHC 1876 (Pat). In KCI

Licensing v Smith & Nephew and HTC v Gemalto

the judges (Arnold J and myself respectively) accepted a significant softening

to what otherwise might have been the rigour of the rule that the title must be

secured by the time the international application is made, by accepting an

analysis based on common law principles distinguishing the equitable and legal

title to property. If the relevant local law meant that the equitable or

beneficial title to the priority right was in the hands of the person making

the priority claim in the international application, that was held to be good

enough even though that person did not then hold the legal title under the

local law and could only perfect their title after the event.

68.

The critical passage in KCI is as follows. Arnold

J had held that on its true construction the relevant agreement there did

convey the legal title to the applicant but he went on to hold that even if

that was wrong, the agreement was effective to transfer the entire beneficial

interest. The applicant had an enforceable legal right to call for a

conveyance of the bare legal title and that made the applicant the “successor

in title” for the purposes of a claim to priority under Article 87(1) of the

EPC and Article 4(A)(1) of the Paris Convention even if KC Inc had not acquired

the bare legal title at the relevant date. After referring to a decision of

the EPO Case J19/87 Burr-Brown /Assignment [1988] EPOR

350, Arnold J held:

“71. To my mind, this makes sense. Article

4(A) of the Paris Convention and Article 87(1) of the EPC are provisions in

international treaties whose operation cannot depend upon the distinction drawn

by English law, but not most other laws, between legal and equitable title. When

determining whether a person is a "successor in title" for the

purposes of the provisions, it must be the substantive rights of that person,

and not his compliance with legal formalities, that matter.”

(Accord’s emphasis)

69.

In HTC I referred to Edwards v Cook

and noted in paragraph 132 that no-one in argument before me had challenged the

proposition that a later acquisition of title to the invention

was not enough. I referred to the above passages from Arnold J’s judgment

in KCI and stated at paragraph 134:

“134. Mr Mellor submitted that this [Arnold

J’s reasoning in KCI] showed that as long as an applicant had, at the

relevant date, what English law would characterise as a beneficial title to the

invention, even if the bare legal title had not been acquired, then the

applicant was a successor in title in the relevant sense. I did not understand

Mr Tappin to dispute that and I think he was right not to. In my judgment if

the relevant person has acquired the entire beneficial interest in the

invention at the relevant time then that should be enough to satisfy the law.”

70.

When Idenix reached the Court of Appeal Kitchin LJ

did not have to express a concluded view on the subject but expressed a

provisional view that KCI and HTC

were correct. Floyd LJ and Patten LJ agreed. Fujifilm

came after Idenix in the Court of Appeal and Henry Carr J

took the same approach.

71.

To return to Idenix, the reasoning of Kitchin LJ

was the following. He noted that Arnold J had held that equitable title was

sufficient, referring to his own KCI judgment and to mine

in HTC. Kitchin LJ then noted that a critical part of the

reasoning was the EPO decision in Burr Brown and then said

the following:

“265. Mr Acland

submits as follows. The judge's analysis starts correctly but jumps to the

wrong conclusion. The signatories to the Paris Convention have a diversity of

legal traditions and it is only the common law that distinguishes between

equitable and legal ownership. Accordingly, the treatment of equitable

interests in English law cannot have any bearing on what the signatories to the

Paris Convention meant by the expression 'successor in title' in Article 4(A).

Instead, one must search for and identify a notion of ownership and transfer of

ownership that is common to all of those signatories.

266. It is my provisional view that the

decisions on this issue in KCI and HTC are correct, that the

Paris Convention does not purport to identify the requirements for the

effective transfer of title to an invention and that these matters are left to

the relevant national law. Indeed this appears to be the approach of the Boards

of Appeal of the EPO: see, for example, T 0205/14 of 18 June 2015. In these

circumstances the notion that it is the transfer of the substantive right and

title to the invention which is important makes eminently good sense.

Nevertheless, it emerged during argument that there may be other materials and

decisions which bear on this issue and to which our attention has not been

drawn. Accordingly and having regard also to the fact that it is not necessary

in this appeal to express a final view on this issue, it seems to me that it is

better left to be decided in another case.”

72.

Although obviously personalities do not come into it, one can see a

personal tinge to Mr Acland’s submissions in this case. In Idenix

his argument which failed is effectively the converse of his argument before

me. Before me his case is that the outcome of applying local law to the facts

is that the substantive right and title to the invention were with Houston on

the day Prof Kohn signed the assignment. So while I do not believe it is

disputed that RCT has those rights today, there is no evidence RCT had them

when it made the application. If, instead of RCT, Houston had filed the

application on 17th March 1997, the assignment assigning the

invention to RCT before the filing date would not have mattered, applying this

line of cases, because even though the bare legal title was with RCT, the

substantive right remained with Houston. Houston could have then filed an

application making a valid priority claim. All Accord’s case amounts to is the

logical consequence of the decisions above.

73.

RCT’s response to this submission has two aspects. First is on the

facts. RCT submits that the court should hold that in fact the assignment by

Prof Kohn was effective to ensure that RCT acquired the substantive priority

right. This factual argument is put on two bases. One that as a matter of

fact I should infer that all the relevant steps did take place and the state of

the evidence is explained by the 20 year time gap. I am invited to hold that

Houston did decide to offer lacosamide to RCT before the assignment and RCT

accepted it and Houston directed Prof Kohn to transfer it to RCT such that the

assignment was therefore effective to assign both legal and equitable title.

The other approach on the facts is to argue that in any event RCT is equity’s

darling, the bona fide purchaser for value without notice (which under the

relevant US law is provided for by statute) and therefore the assignment was

effective to leave RCT with full title despite Houston’s equitable rights.

74.

Second RCT submitted that even if either of those points were not right,

there was nevertheless a transfer of the equitable title to RCT. However its

case on this was incoherent. RCT did submit that the proposition that a person

with full equitable title but no legal title can claim priority is not

“reversible” and does not imply that the person with legal title may not claim

priority unless they prove they also hold the full equitable interest, but

there was no analysis to back this up. There was a suggestion by RCT that in KCI

it was held by Arnold J at paragraph 68 that the legal title was sufficient.

That is not accurate. By “sufficient” RCT must mean to suggest that the judge

had held that legal title was sufficient even if the equitable title was elsewhere.

That is not what Arnold decided. In KCI the relevant

company held the equitable title anyway. RCT’s submissions on principles also

contained references to a number of equitable maxims such as “equity does not

assist a volunteer” but the submission did not make sense and the point was not

pursued. I will approach this aspect of the case as a submission that under US

law (Federal and Texas law) an implied in fact agreement to assign the

equitable interest to RCT should be found to exist and was effective to assign

the interest at the same time as the February 1997 assignment. The US law

aspects of this submission are addressed below.

75.

I find that the legal principles applicable to priority entitlement are

settled at this first instance level. They are:

i)

Usually the right to claim priority goes with the right to the

invention. That is uncontroversial.

ii)

The right to claim priority must be with the person making the patent

application in which that right is claimed when they make that claim, i.e. when

the application is filed. A later acquisition of that right cannot make good a

lack of it on the relevant date. If the right was not in place at the time

then the right is lost for all time. That is Edwards v Cook.

iii)

But if the local law applicable to rights of the applicant and the

patent application at the place and time when it was made allows for a

splitting of property rights into legal and equitable interests, then it will

be sufficient to establish an entitlement to priority if the applicant holds

the entire equitable interest at the relevant date. That is KCI,

HTC and FujiFilm and was held in the

Court of Appeal in Idenix provisionally to be correct.

iv)

A person with a legally enforceable right to call for the assignment of

the legal title to a piece of property such as an invention (or a right to

claim priority) has the equitable title to that property. When the cases refer

to the applicant holding the substantive right and title to the invention, they

are referring to this legal/equitable distinction.

76.

In my judgment Accord is right in law that following from those

principles, a person who at the relevant time and under the relevant applicable

law, acquired only the bare legal title to an invention and not the equitable

title, when the equitable title is held by another, does not then hold the

substantive right and title to the claim to priority.

77.

However I cannot help but observe that if priority is lost this patent

would be revoked over a publication by the inventor in the period between the

priority date and the filing date which I infer was assumed to be a safe thing

to do because it was assumed by everyone involved that priority would be

successfully claimed. There will be many cases like this. There is no obvious

public interest in striking down patents on this ground, unlike all the other

grounds of invalidity. The difficulty starts with the point that the title

cannot be fixed retrospectively. If I may say so the reasons given by Kitchin

J in Edwards v Cook are compelling reasons why that should

be so. However the legal/equitable analysis chips away at that principle since

what is happening in those cases is that the equitable owner’s imperfect title

on the relevant date is only perfected after the event. No doubt that is why,

in the Court of Appeal, Kitchin LJ declined to get into the issue any further

since he did not have to.

78.

I offer the following tentative suggestions. One approach could be that

the effect and devolution of the priority right has to be purely governed by a sui

generis law applicable to priority rights in all signatory states to the

Paris Convention equally and applicable in all those states regardless of

whether those states recognise a legal/equitable distinction. Flaws in the title

cannot be fixed retrospectively. That is one way of interpreting Edwards

v Cook and there are good reasons for it. However it does not sit

happily with the equitable/legal distinctions made in the later cases. An

alternative could be to apply the same approach and the same applicable law to

the priority claim as applies to ownership of the invention and the right to

the patent. In a case in which there is some doubt about the claimant’s title

to the patent itself, that title has to be perfected by the judgment e.g. by

assignment or the legal owner must be joined to the proceedings (see e.g. Baxter

v NPB [1998] RPC 250). The moment the title to the patent matters

is judgment. In this case the moment the priority claim matters could be said

to be the judgment. As far as the applicable law is concerned, under English

private international law, the law applicable to the devolution of the rights

to the invention in Texas in 1996/97 is US law, which is in fact a mix of

Federal and Texan state law. Nevertheless regardless of these tentative

suggestions, I will apply the law as it is settled at this level.

Assessment –

priority

79.

It was common ground between the US law experts that there existed

between Prof Kohn and Houston an agreement whereby the professor would assign

his rights in any relevant inventions to Houston or its designee. The parties

helpfully prepared a set of agreed principles of US law. Agreed Principle 14

was that:

“Where there is a valid and enforceable promise to assign in

the future all rights in a future invention, patent application or patent, the

promise holds equitable title in the invention, patent application or patent.

Upon the invention being made, the patent application being file or the patent

being issued the promisee is entitled to demand the transfer of the legal title

and to compel the same by way of civil proceedings. Where a promisee holds

such an equitable interest, to gain legal title to an invention, patent

application or patent the promisor must transfer legal title by a written

assignment from the promisor-assignor after the invention is made, the patent

application is filed or the patent is issued.”

80.

Applying that principle leads to the conclusion that when Prof Kohn made

the lacosamide invention, Houston held the equitable interest in it.

81.

The only dispute about US law was or seems to be about whether the

transfer of equitable title to a patent requires a “clear and unmistakable act

of assignment” in order to part with the rights. In his first report Prof Merges

refers in both paragraphs 40 and 58 to the need for a clear and unmistakable

act of assignment to transfer an equitable interest. Prof Chisum did not

agree, expressing the view in his second report (paragraph 21) that such a

requirement was inconsistent with the principle that an “implied-in-fact”

contract could convey an equitable title, which principle had been expressed by

Judge Davis and which Prof Chisum agreed with. Accord submitted there was no

inconsistency between the view that an “implied-in-fact” contract could convey

an equitable interest and Prof Merges’ opinion, because the implied-in-fact

contract was simply an example of the necessary clear and unmistakable intent

required by Prof Merges being found to exist evinced by conduct.

82.

RCT relied on findings of US law in the judgment of Henry Carr J in Fujifilm

under s4(2) of the Civil Evidence Act 1972. The point is that although foreign

law is a question of fact, under s4(2)(b) the foreign law can be taken in this

trial to be in accordance with the earlier judgment unless the contrary is

proved. The two points decided by Henry Carr J as US law were:

i)

That there are no special requirements under US law for: (i) a person or

company to be nominated under an agreement to be the beneficiary of rights; or

(ii) that party to be expressly identified in a contract providing for

assignment to a nominee before the agreement can take effect (FujiFilm

paragraph 49); and

ii)

implied-in-fact contracts are not limited to the field of employed to

invent (FujiFilm paragraph 55).

83.

I accept both propositions. RCT says that the first proposition is

contrary to Prof Merges’ opinion. Accord’s submission is that it is not

because the first proposition from Fujifilm is concerned

with formalities, or rather the absence of them whereas, as Accord puts it in

its closing:

“262. […] The issue is not whether there are special

requirements for a person to be nominated, but the standard of proof necessary

to show that a person has been nominated (regardless of the means by

which that nomination occurs). This is particularly important where the method

by which the nomination is said to have occurred is by an implied contract.

There is no extra “requirement” upon them to nominate in a particular way (for

example in writing, etc.), merely to prove to the Court’s satisfaction that

there was in fact a nomination (by any means) which demonstrated the necessary

clear intent to part with the patent rights.

84.

This is an accurate reflection of the way Accord puts its case. Neither

side addressed the question whether the standard of proof is a matter for the lex

fori and I will not do so either.

85.

My findings on this point are the following. An implied in fact

contract, inferred from matters such as the conduct of the parties is capable

under US law of transferring an equitable interest. There are no special

requirements, in the sense of formalities, under US law for a person to be

nominated as the beneficiary of rights. What must be proved is a clear

intention by the parties that a person was in fact nominated. In that sense it

must be clear and unmistakable.

The evidence

86.

RCT’s case is based on witness statements from Professor Kohn, Mr

Reckart and Dr Krishnamoorti. Accord did not seek to cross-examine the latter

two witnesses at all. At the pre-trial review Accord raised the question of

cross-examination of Professor Kohn. I refused to permit Accord to

cross-examine the witness on case management grounds. At that stage Accord’s

challenge to priority was much broader than the single point now taken.

Importantly Accord only advanced one reason why they wanted to cross-examine

the professor; it was about his awareness in 1997 of a policy document from the

university. That did not justify cross-examination and so it was refused. The

point on Professor Kohn’s awareness of a policy document has nothing to do with

the issue I now have to decide.

87.

Professor Kohn’s general evidence comes down to the following:

i)

He does not recall having, or signing, any formal employment contract on

joining Houston or subsequently.

ii)

Throughout the FAA Project, Professor Kohn understood that he would not

own the rights in his inventions, nor any patents in those inventions.

Moreover, he understood he would assign any rights to RCT if required by Houston.

iii)

In return, upon commercialisation of any of his work by RCT, Professor

Kohn and Houston (together with members of his laboratory group) would receive payment

from RCT.

iv)

The work described was all part of a single project, the FAA Project. The

various strands of work, including the work on lacosamide, all fell within the

FAA Project.

v)

Professor Kohn understood that the arrangement between Houston, RCT and

himself was the same for lacosamide as it had been agreed to be for all the

other work within the FAA Project. He started the work which led to the FAA

project in 1973. Six patent applications were assigned to RCT under the FAA

project before lacosamide.

88.

Pausing there, two matters can be mentioned. One relates to paragraph

(ii). Professor Kohn’s witness statement is clear in this respect that he

understood he would assign to RCT if required by Houston. A question is

whether he ever was required by Houston to assign lacosamide.

89.

The other matter is that RCT submitted that these points and point (iv)

in particular meant that it was therefore a reasonable assumption of any party that

the same arrangements that had applied to the previous work within the FAA

Project would apply equally to the lacosamide work. It depends what you mean.

I accept that lacosamide was governed by the terms which governed the FAA

project, in effect the 1966 agreement. However what is clear, as Accord

submitted, is that the proper process required a decision by Houston to offer

to RCT (and so on) as was followed for other inventions in the FAA project.

There is no basis for assuming that a previous decision by Houston to offer a

particular invention made in the FAA project (i.e. a particular set of

compounds) applied to another different invention made later in the same

project (i.e. lacosamide). Moreover there is no evidence that Professor Kohn

made such an assumption on that basis. He does not say that is what he did.

90.

Turning to lacosamide specifically, Professor Kohn’s evidence is that in

1993 he identified twelve FAA compounds (including lacosamide) as worth

testing. He does not mention the work reported in the earlier Le Gall thesis

but nothing turns on that.

91.

No invention disclosure document is now in the possession of RCT.

Professor Kohn explains he told RCT about lacosamide (and the corresponding

racemate) in correspondence. He used the same FAA project number as before.

There were pharmacological tests run on the compounds at an organisation called

NINDS which is in effect the NIH. There is evidence of discussions between the

professor and RCT in 1993/94 about RCT being authorised by the professor to

discuss those results with NINDS. Professor Kohn’s evidence about this is

clear that he was working on the basis that RCT were responsible for patenting

these compounds. What is not said is why. There is no reference to Houston

having made a decision to offer the compounds to RCT. A fair reading of this

evidence is that Professor Kohn simply assumed that RCT were responsible for

patenting all FAA compounds.

92.

By October 1994 Professor Kohn had obtained “neat test results” from the

NIH for lacosamide. That expression comes from a letter from him to RCT which

discussed RCT taking action on licensing. Neither this letter nor the previous

letters show on their face that they were copied to Houston. That of course

does not mean they were not.

93.

An issue arose in early 1996 to delay publication of Daeock Choi’s PhD

thesis pending filing of the first priority application in March. Professor

Kohn wrote to Dr Bear, the Dean of the College of Natural Sciences and

requested the delay, as he put it to Dr Bear because “it is very important to

protect the university’s interests”. Publication was delayed and the priority

application was filed by Professor Kohn in March 1996 with the assistance of

RCT.

94.

A week later Professor Kohn wrote to Dr Robbins, the Director of

Technology at Houston because RCT had made a payment under the FAA project.

The letter was concerned with identifying which members of the Professor’s

group were entitled to a share. It is not clear what exactly this payment was

for. I do not accept the suggestion (if made) that this was a stage payment

arising from a decision by RCT to accept an offer of lacosamide by Houston.

95.

On 4th February 1997 Professor Kohn completed the assignment in favour

of RCT which has been referred to already. In his statement Professor Kohn states

that he felt that assigning his rights in the lacosamide invention made sense

to him in light of the relationship between Houston and RCT, and the manner in

which previous FAA inventions had been dealt with. This makes sense but note

that here the Professor is referring to assigning his own rights to RCT and not

to assigning Houston’s rights.

96.

Professor Kohn refers to the FAA project as a whole, the fact that

payments were made by RCT, and that there was regular communication and annual

reports from RCT. He says he kept in close contact with Houston about the

inventions and that he took care to keep Houston informed of his dealings with RCT.

The contacts included telephone calls as well as carbon copies of letters.

Professor Kohn says that all three parties (Professor Kohn, Houston and RCT) were

in contact throughout and Houston never once suggested that they were anything

other than fully content with Professor Kohn’s co-operation with RCT pursuant

to arrangements described. He said that Houston never once suggested to him that

it did not fully endorse his passing of information about the FAA inventions to

RCT or assigning his rights in these inventions to them.

97.

Professor Kohn states that one of his relevant contacts at Houston’s Office

of Sponsored Research and Technology Transfer Department was Mrs Judy Johncox.

That matters because (and I find) that department would be the correct part of

the university to make a decision to offer an invention to RCT and because (and

I find) Mrs Johncox would be one of the relevant individuals to participate in

such decision making. I will return to Mrs Johncox below.

98.

The professor ends his witness statement by summarising that his

understanding was that he would not own the rights in the inventions but that

he would assign them to RCT in accordance with Houston’s wishes.

99.

Turning to Dr Krishnamoorti’s evidence, this can be addressed much more

briefly. He was not at Houston until well after the relevant events. He

explains that lacosamide is the most successful technology transfer undertaken

by Houston and has earned the university over $50 million to date with more to

come. He is not aware of any disputes about ownership arising out of the FAA

project or any suggestion that Houston does not or did not consider that RCT

was entitled to the rights it has. He says that based on current practice,

which as far as he is aware is the same now as it was then, either Houston

would have assigned the intellectual property to RCT or to the extent that

Professor Kohn had not executed an assignment in favour of Houston, Houston

would have required Professor Kohn to assign their interests directly to RCT.

100.

Mr Reckart’s evidence explains the origins of RCT. He was RCT’s general

counsel from 1986 to 2001 and therefore can speak from first hand experience.

He explains how the FAA project ran and explains the usual procedure of

notification to RCT of the inventions and acceptance. In this respect

(paragraphs 23-35) he is talking about the time before lacosamide.

101.

In relation to lacosamide Mr Reckart’s evidence deals with the same

correspondence between Professor Kohn and RCT in 1993/94 discussed by Professor

Kohn. In relation to the filing of the priority document by Professor Kohn in

March 1996 with RCT’s assistance, Mr Reckart points out that as part of that

filing a declaration was filed which he signed on 8th March 1996.

The declaration is about the “small business” status of RCT. It states that

the rights in the invention have been conveyed to RCT. The form includes a

statement that the signing person is aware that willful false statements are

punishable by a fine or imprisonment. The timing of this declaration implies

that if there had been a decision by Houston to offer the invention to RCT and

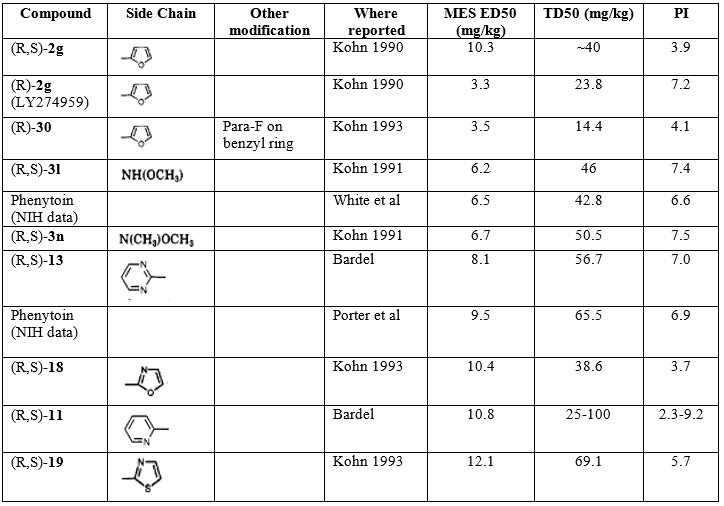

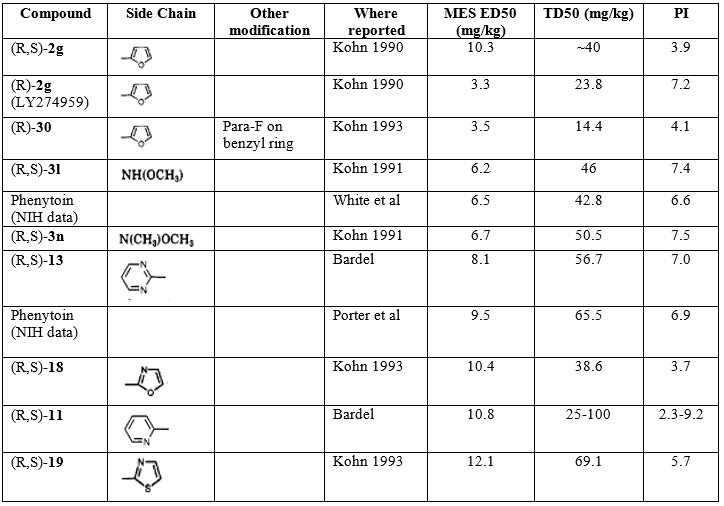

an acceptance of that offer by RCT, it most probably happened before 8th

March 1996.

102.

Mr Reckart refers to an agreement for a joint collaboration signed in

September 1996 by Houston, RCT and Queens University of Kingston, Ontario,

Canada. He says that this arose following Professor Kohn’s invention of

lacosamide and was to look into new CNS active agents. On behalf of Houston

the agreement is signed by Dr Arthur C. Vailas, the Vice Provost of Research.

The agreement records that RCT has patents arising from inventions made at

Houston and gives a project number which is the FAA project number. There is

no express reference to lacosamide.

103.

On 10th January 1997 Mr Reckart wrote to Ms Johncox at

Houston (copied to Dr Vailas). The letter refers to the priority application

from a year before, that is the one which includes lacosamide, and informs her

that a PCT application was going to be filed. I am not aware of any reply to

that letter. RCT emphasises that Ms Johncox was in the department of the

university which would make or would have made a decision to offer inventions

to RCT. That would also explain why Ms Johncox is the person to whom Mr

Reckart was writing about patent applications.

104.

In relation to the February 1997 assignment, Mr Reckart states that in

his view it is consistent with the 1966 agreement whereby the university may

recommend to faculty members to assign their inventions to RCT. I accept that

the assignment is consistent with the agreement (see clause 3 which is

addressed below).

105.

Mr Reckart explains that RCT kept Houston up to date on patent

prosecution after this.

106.

Finally, in closing RCT produced a disclosure list from which it

submitted that one can infer many documents from the relevant period have been

lost.

Inferences

107.

That concludes my summary of the evidence. RCT submitted I should infer

from this evidence that the procedure under the 1966 agreement had been

complied with and therefore Houston had decided to offer lacosamide to RCT and

the Professor’s assignment to RCT had been done because Houston had required

him to do it. Alternatively I should infer the existence of an implied in fact

contract effective to assign the equitable interest. Finally and in any case I

should find that RCT were in the position of a bona fide purchaser for value

without notice and so took good title under the 1997 assignment even if Houston

still had equitable title at the time it was executed.

108.

Accord submitted that the principles identified by the Court of Appeal

in Wisniewski v Central Manchester Health Authority

(unreported 1st April 1998 Roch, Aldous and Brooke LJ) and by the

Supreme Court in Prest v Petrodel [2013] UKSC 34 meant

that the court was precluded from drawing the relevant inferences.

109.

The leading judgment in Wisniewski was given by

Brooke LJ, which whom Roch and Aldous LJJ agreed. After citing a number of

authorities including Herrington v BRB [1972] AC 877 the

judge summarised the principles as follows:

"(1) In certain circumstances a court may be entitled to

draw adverse inferences from the absence or silence of a witness who might be

expected to have material evidence to give on an issue in an action.

(2) If a court is willing to draw such inferences they may go

to strengthen the evidence adduced on that issue by the other party or to

weaken the evidence, if any, adduced by the party who might reasonably have

been expected to call the witness.

(3) There must, however, have been some evidence, however

weak, adduced by the former on the matter in question before the court is

entitled to draw the desired inference: in other words, there must be a case to

answer on that issue.

(4) If the reason for the witness's absence or silence

satisfies the court then no such adverse inference may be drawn. If on the

other hand there is some credible explanation given, even if it is not wholly

satisfactory, the potentially detrimental effect of his/her absence or silence

may be reduced or nullified.”

110.

Accord then referred to paragraphs 43-45 of the judgment of Lord

Sumption in Prest v Petrodell. In the first paragraph

Lord Sumption explains that what is in issue depends on what presumptions may

properly be made against a husband given that the defective nature of the

material is down to his own persistent obstruction and mendacity. There are

then references to Herrington, to R v IRC ex

parte Coombs [1991] 2 AC 283 and to Wisniewski.

Subject to an irrelevant caveat about matrimonial cases, Lord Sumption states

the principle in paragraph 44 as being that:

“There must be a reasonable basis for some hypothesis in the

evidence or the inherent probabilities, before a court can draw useful

inferences from a party’s failure to rebut it.”

111.

The reliance by Accord on Prest v Petrodell and on

some of the statements in Wisniewski seeks to portray

Professor Kohn as an absent witness or to portray RCT as a litigant who elected

to call no relevant witnesses. That would be unfair. I have addressed the

pre-trial review already.

112.

Nor is it really fair to say that any of RCT’s witnesses are “silent”

given their extensive evidence directed to the issues. However the real point

Accord is making is that Professor Kohn does not state in terms that he

disclosed lacosamide to Houston first before disclosing it to RCT, nor that

(regardless of when his disclosure to Houston took place) in any event the

university actually did make a specific decision to offer lacosamide to RCT and

then directed Professor Kohn to execute an assignment in RCT’s favour. None of

the other witnesses say that either. Therefore, the argument goes, given this

absence of evidence, the court should not infer that something happened when

the witnesses do not say that it did.

113.

I have no doubt that from his own point of view, Professor Kohn at all

times did what he did because he thought he was obliged to the university to do

so and because he thought the university thought he should. However reading

Professor Kohn’s evidence as a whole, it seems to me that by the time

lacosamide was identified he also thought or assumed that the university was

obliged to assign any FAA invention to RCT. The heart of the problem is that

this has not been established (and I find would not be correct). However this

assumption on the professor’s part may explain where the problem arises.

114.

I am not satisfied I can draw the inferences of fact necessary to

support RCT’s primary case that the procedure under the 1966 agreement had been

complied with before 4th February 1997. This depends on what did or

did not happen as between Professor Kohn and the university. For example one

approach which RCT’s case invites me to take is to infer that Professor Kohn

must have completed an invention disclosure document for lacosamide for

delivery to the department in Houston in order for them to make the decision

whether to offer that invention to RCT and for the document to then be passed to

RCT. The fact such a document is not available in disclosure today from either

RCT or Houston must therefore be simply because it has been lost. But

Professor Kohn does not say that is what did happen nor does he even say that

it is what must have happened albeit he now has no recollection of it. The

most he says is that RCT does not today have any formal invention disclosure

document but he does not even state in terms that such a document ever

existed. He is simply silent on that point. In my judgment it would be wrong

to infer that such a document must have existed but has been lost, without at

least some statement to that effect by a witness or in a disclosure list. RCT

referred to a list of what has been disclosed in closing but that list does not

help. It does not, for example, include an invention disclosure document as a

document which did exist but has now been lost.

115.

The same problem arises with the other inferences necessary to support

this part of the case. I cannot infer that the university made a decision to

offer lacosamide to RCT. Neither Professor Kohn or Dr Krishnamoorti say that

is what happened nor, again, does Professor Kohn say that it must have happened

albeit he has forgotten. All Professor Kohn does is give generalised evidence,

which I accept, that the university was aware of what he was doing. That does

not mean that they had made a specific decision about lacosamide. The same

problem also arises for an inference that the university instructed Professor

Kohn to execute the assignment on 4th February 1997. He does not

say that that is what happened.

116.

Similarly I cannot make the findings necessary to infer the existence of

an implied in fact contract to assign the equitable interest. That fails for

the same reasons. There is nothing from which to infer that the university

actually did intend that the lacosamide invention should be patented by RCT.

There is no evidence the university thought about it at all.

117.

I find that on the date Professor Kohn executed the assignment to RCT,

he held the bare legal title to the invention (including the priority right)

but Houston held the beneficial or equitable title. The Professor thought he

was doing what he was supposed to do in executing that assignment but the

assignment was not an assignment of Houston’s equitable interest.

118.