3. As pleaded, this trial was to concern:

i) Whether the Patent is valid, with validity challenged on numerous grounds;

ii) Whether the Patent is essential/infringed;

iii) Whether, if the Patent is valid and infringed, Apple has a defence of proprietary estoppel arising from the way in which the former owner of the Patent, Ericsson, behaved in relation to the adoption of the solution of the Patent into the LTE standard.

14. The issues narrowed in the run up to trial, and during trial. The remaining issues are:

i) The nature of the skilled team, where there was minimal disagreement.

ii) The scope of the common general knowledge. There were only minor issues over this.

iii) Claim construction. There were multiple issues and they are critical to (in particular) the anticipation arguments.

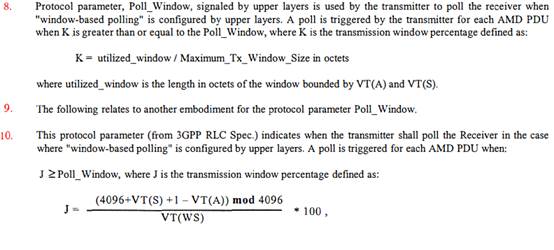

iv) Anticipation over a patent application referred to as “Pani” (PCT Application WO 2008/097544). Pani was prior art for novelty only. Novelty has to be assessed for the granted claims and, if those are anticipated, in respect of conditionally amended claims.

v) Anticipation and obviousness over prior art referred to as “InterDigital” (TDoc R2-071618). In relation to anticipation, I allowed an application at the start of trial by Apple to plead anticipation by equivalence as well as on the ordinary, purposive meaning of the claims.

vi) Whether the proposed amended claims are allowable or whether they lack clarity or add matter.

21. Apple made a number of criticisms of Mr Kubota apart from his expertise:

i) That he gave evidence as an advocate not an expert. Insofar as this was a comment based on his demeanour, I reject it. Certain examples were given which I will now move on to.

ii) That in connection with InterDigital he said it was complex in relation to anticipation and simple when it came to obviousness. This was a bad point, since what he said was that windows-based approaches have more complexity than counter-based ones, which is true, and that InterDigital itself claims to be simple, which is also true. It was also a very small point even if correct, not justifying a personal criticism.

iii) That he avoided using the word “count” and instead used verbs like “observing”. Since a crucial issue in the case is what “counting” means, it was wise to avoid its use in disputed or potentially ambiguous contexts.

iv) That he read Pani too literally and not with adequate regard to the CGK. Since Pani was a novelty-only citation it was necessary to avoid obviousness-type considerations in assessing it. If Mr Kubota was a bit too literal, which he perhaps was (on whether the counter was taught as incrementing, a minor issue), it was not because he was being an advocate.

v) That the length of time he spent over answers on P3 supported the inference that he had not read it before, even though he said he had. The inference was not remotely justified. He obviously knew it quite well and was taking his time. I was surprised to see this point maintained in Apple’s written closing.

vi) That his collation of TDocs in exhibits KK2 and KK3 and his evidence based on them were not fairly put together because where companies initially expressed one opinion consistent with his thesis, but changed their opinion and ended up taking positions that were inconsistent, he mentioned their initial opinion. I agree that this was a slightly odd way to present things, but accept his explanation that he was working through things chronologically. His written evidence acknowledged the changes of view explicitly not long after stating the initial opinions, so he did not conceal anything.

30. Optis went further and criticised Mr Rodermund as a partial, unbalanced witness who lacked independence and was an advocate for Apple. It supported these criticisms with examples where it said Mr Rodermund had quoted selectively. It was reasonable to explore and make these points and there was force in them (although I thought they related only to his written evidence, since his oral evidence was straightforward and fair), but not so much as Optis contended. The real problem was the scope of what he had been asked to do, which was to provide materials supporting a view that his understanding of clause 4.1 could work, and that there were policy views, held by some, that it was how the clause ought to work. It was an extremely abstract, theoretical approach and I do not think that it engaged with the issues for decision by me. To give an example, Mr Rodermund was criticised with particular force for not acknowledging in his evidence here, the reports Ms Dwyer had submitted in the Texas proceedings about ETSI members’ actual behaviour. He simply had not done that because he had not been asked to, but he had not concealed it at all. Another example was in relation to whether IP was discussed by Working Group members prior to, or at, their meetings: Mr Rodermund found some materials where it appeared that that might have happened, but on examination they did not hold water. He was again, I felt, concerned with the theoretical and not the actual.

61. The available triggers in the UMTS system were referred to in evidence as a “tool box”. They included end of transmission polls: “Last PDU in buffer” and “Last PDU in Retransmission buffer” which are self explanatory. The defined polls also included the following (at paragraph 9.7.1 of 3GPP TS 25.322 V7.5.0):

i) “Poll timer”. A timer is set when a poll is triggered and stopped in certain circumstances (such as when the right status report is received). If no status report appears before the timer runs out a further poll is sent. This aims to ensure that when a poll is sent, it is answered correctly.

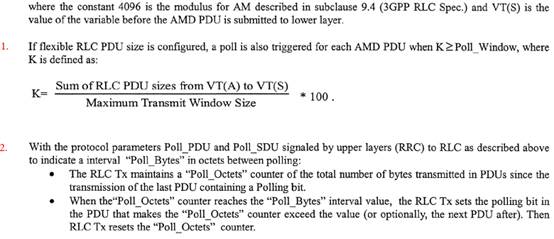

ii) “Every Poll_PDU PDU”. This is a PDU counter. The system counts the number of PDUs sent and when that number reaches the value in the field “Poll_PDU” a poll is triggered.

iii) “Every Poll_SDU SDU”. This is an SDU counter. The system counts the number of SDUs received and when that number reaches the value in the field “Poll_SDU” a poll is triggered. To be precise the poll is triggered on the first transmission of the AMD PDU which contains the last segment of the RLC SDU.

iv) “Window based”. This triggers a poll when the parameter “J” reaches a threshold. The parameter J is defined as:

* 100

* 100

J represents the percentage occupancy of the sequence number window at the transmitter. A poll is triggered for each AMD PDU where J ≥ Poll_Window. The term “(4096 + …) mod 4096” accounts for the fact that in UMTS sequence numbers wrap around to zero after passing 4095, and the “+1” term is for the next PDU to be transmitted.

v) “Timer based”. This triggers a poll periodically based on a timer.

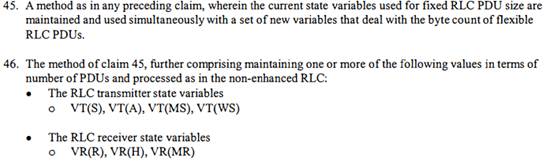

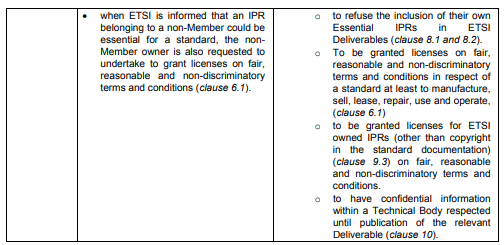

67. TS 25.322 V7.5.0 provided at its section 9.4 a list of state variables which the transmitter was required to maintain. The most relevant ones are set out below:

i) VT(S) - Send state variable.

This state variable contains the "Sequence Number" of the next AMD PDU to be transmitted for the first time (i.e. excluding retransmitted PDUs). It shall be updated after the aforementioned AMD PDU is transmitted or after transmission of a MRW SUFI which includes SN_MRWLENGTH >VT(S) (see subclause 11.6).

The initial value of this variable is 0.

ii) VT(A) - Acknowledge state variable.

This state variable contains the "Sequence Number" following the "Sequence Number" of the last in-sequence acknowledged AMD PDU. This forms the lower edge of the transmission window of acceptable acknowledgements. VT(A) shall be updated based on the receipt of a STATUS PDU including an ACK (see subclause 9.2.2.11.2) and/or an MRW_ACK SUFI (see subclause 11.6).

The initial value of this variable is 0. For the purpose of initialising the protocol, this value shall be assumed to be the first "Sequence Number" following the last in-sequence acknowledged AMD PDU.

iii) VT(PDU).

This state variable is used when the "poll every Poll_PDU PDU" polling trigger is configured. It shall be incremented by 1 for each AMD PDU that is transmitted including both new and retransmitted AMD PDUs. When it becomes equal to the value Poll_PDU, a new poll shall be transmitted and the state variable shall be set to zero. The initial value of this variable is 0.

iv) VT(WS) - Transmission window size state variable.

This state variable contains the size that shall be used for the transmission window. VT(WS) shall be set equal to the WSN field when the transmitter receives a STATUS PDU including a WINDOW SUFI.

The initial value of this variable is Configured_Tx_Window_size.

81. The parties identified the areas of disagreement on the CGK as lying in the following areas:

i) The nature of counter-based and windows-based polling. I do not think this was really an issue about CGK, since both counter-based and windows-based polling are agreed to have been CGK at the level indicated above. There is a significant dispute about the different consequences of the two approaches, which I will address in connection with the prior art.

ii) Sliding windows, windows-based operation, the J-equation: these were identified as potentially disputed by Apple, but they were not disputed and are covered in the agreed document.

iii) Stalling and causes of stalling: likewise, these were identified as potentially disputed by Apple but were not.

iv) Poll prohibit timers and status prohibit timers: there was a dispute about this and I address it below.

v) Scheduling algorithms, round trip times and whether it was realistic for no further PDUs to be transmitted between poll trigger sending and receipt of a status report: these go together and I will address them below.

vi) “The direction of the art”. Mr Kubota presented in evidence an analysis of TDocs which were said to show a preference in the art for window-based polling over counting-based. Depending on the view one takes, this was either “mindset” material, or secondary evidence of non-obviousness in relation to InterDigital. I will deal with it in connection with InterDigital.

92. Then, at [0005] to [0007] it sets out aspects of the draft LTE standard as it stood at the time, including two criteria for setting the poll bit:

“[0005] The RLC protocol applied in an evolved UTRAN (E-UTRAN), also denoted Long Term Evolution (LTE), has been defined in the document 3GPP TS 36.322 "Evolved Universal Terrestrial Radio Access (E-UTRA), Radio Link Control (RLC) protocol specification Release 8" issued by the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP). The RLC protocol includes a polling procedure that transmits polls according to a number of criteria. When a poll is triggered the RLC transmitter will set a poll bit in the RLC header, the poll bit serving as a request for a peer entity to send an RLC status report. Currently agreed criteria for setting the poll bit are:

[0006] Firstly, transmission of last Protocol Data Unit (PDU) in a buffer, i.e. a poll is sent when the last PDU available for transmission or retransmission is transmitted.

[0007] Secondly, the expiry of a poll retransmission timer, i.e. a timer is started when a PDU containing the poll is sent and the PDU is retransmitted if the PDU with the poll bit is not acknowledged when the timer expires.”

94. It then compares counter-based and window-based mechanisms at [0009] and [0010]:

“[0009] A counter-based mechanism counts the amount of transmitted PDUs, or bytes, and sets the poll bit when a configured number of PDUs, or bytes, have been transmitted.

[0010] A window-based mechanism is similar but transmits the poll only when the amount of outstanding data exceeds a certain number of PDUs, or bytes. A window-based mechanism may need additional logic to transmit the poll regularly as long as the amount of outstanding data exceeds the threshold.”

101. Claim 1 of the Patent (broken into integers, taken from Apple’s opening skeleton with some typos corrected and the italicisation, on which nothing turns, reinstated) is:

(a) Method in a first node (110) for requesting a status report from a second node (120), the first node (110) and the second node (120) both being comprised within a wireless communication network (100),

(b) the status report comprising positive and/or negative acknowledgement of data sent from the first node (110) to be received by the second node (120), wherein the method comprises the steps of:

(c) transmitting (306) a sequence of data units or data unit segments to be received by the second node (120), the method further comprises the steps of:

(d) counting (307) the number of transmitted data units and

(e) the number of transmitted data bytes of the transmitted data units, and

(f) requesting (310) a status report from the second node (120)

(g) if the counted number of transmitted data units exceeds or equals a first predefined value, or the counted number of transmitted data bytes of the transmitted data units exceeds or equals a second predefined value.

103. Claim 9 is then as follows:

(a) Method according to any of the previous claims 6-8,

(b) wherein the steps of resetting (311, 312) the first counter (421) and the second counter (422) is performed

(i) when the first predefined value is reached or exceeded by the first counter (421)

or

(ii) when the second predefined value is reached or exceeded by the second counter (422).

142. Apple’s case was essentially that the “or” in claim 9 provided an option as to which counter was to be tested, but without requiring that both be. I find it a little hard to articulate how this would be expressed in English without being cumbersome, but the effect was that:

i) One option to meet the claim would be to have a method in which only the byte threshold was tested, and both counters reset if it were reached;

“or”

ii) Another option to meet the claim would be to have a method in which only the PDU threshold was tested, and both counters reset if it were reached;

145. Apple’s main arguments in support of its construction were:

i) That there would be a benefit from each option, and the benefit of having a reset if either threshold were met, by testing both, was merely additive. In a general sense this is true (although I do not think it was made good that the benefit of testing both thresholds would be merely additive in a strictly mathematical sense), but it does not mean that the patentee would not want to have a claim directed to the arrangement which maximised the reduction of superfluous polling.

ii) That a construction which required both thresholds to be tested would distort the word “or” so that it meant “and”. I found this hard to follow. “Or” can perfectly well be used to mean that something is to be done if either of two conditions are met: “I take the bus to work if it is raining or if I am late”. This can be rewritten to use “and”: “I take the bus to work when it is raining and when I am late”. In each case I have to turn my mind to the weather and the time to decide whether to take the bus. There was no dispute that “or” was used in that sense (either of two tested conditions) in claim 1, and it is also the sense in which it is used in the pseudocode.

iii) That it was the literal and ordinary English meaning. I disagree with this for reasons just given.

iv) That the Patent specification contains a lot of broadening or inclusive language, which extends (see [0086] and [0090]) to making the reset of each counter optional. This is true but does not add anything if, as I find, the reader would think that the meaning of claim 9 was closely informed by the pseudocode. As to [0086] and [0090] specifically, they do not help given that the resets to which they refer are both mandatory in claim 9.

v) That [0118] contains a definition of “and/or” such that it “includes any and all combinations of one or more of the associated items”. This is not a definition of “or”, but in any case it does not help: there is no dispute that “or” in claim 9 means that the PDU threshold and the byte threshold are both potentially relevant. The dispute is how they are processed in the logic of the method.

vi) That claim 11 uses “or” in the same way as claim 9. Claim 11 says that the first node “is a base station or a radio network controller ‘RNC’ … or an evolved Node B, ‘eNodeB’”. This is a false equivalence. Claim 11 is talking about what a physical component used in the method is, when that component cannot be e.g. both an RNC and an eNodeB at the same time.

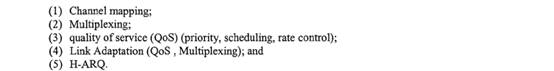

172. As well as referring again to “enhancements”, this is a disclosure that developments on top of sequence number/PDU counting would be needed to cope with variable length PDUs. This is taken on by 4/6, which says that:

6. The main aspect of the present invention introduces byte count based methods to enhance the RNC/Node-B flow control, RLC flow control, and status reporting when RLC flexible PDU size is configured with a specified maximum RLC PDU payload size. These enhancements will enable efficient operation of the RLC functions which are currently based on RLC PDU sequence numbers. Moreover the RLC enhancements proposed here apply to:

l both uplink (UE to UTRAN) and downlink (UTRAN to UE) directions; and

l the architecture where the RLC is move fully or partially to Node-B

174. 4/9 then says as follows:

9. With Flexible RLC PDU size using the number of PDUs to define window size will result in variable window size and buffer overflows in the RNC while having potential underflows in the Node-B. Hence, the preferred embodiment includes the following metrics for defining window size when flexible RLC PDU size is configured:

l Number of bytes

l Number of blocks where each block is a fixed number of bytes

l Number of PDUs or Sequence Numbers

l All possible combinations of the above three metrics

213. It explains the thinking behind this in section 2:

“RLC Window Configuration

The existing window-based polling mechanism is based on sequence numbers. When flexible RLC PDU size is configured, large RLC PDU sizes will be transmitted and the RLC receiver window memory will fill up well before the current criterion for window-based polling is met if a typical value is used for the Poll_Window parameter (e.g 90%). This will result in transmission stalling.

To alleviate this issue one could configure the Poll_Window parameter with a much smaller value, such as 20%, to ensure that polling is always triggered before the memory is exhausted. However, this is not a viable solution as it would result in premature polling when smaller RLC PDU sizes are transmitted.”

220. I next need to go into the J calculation in more detail. Some points worth mentioning and/or repeating at this stage are:

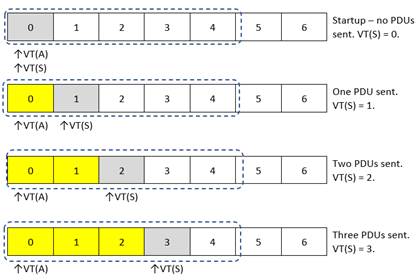

i) VT(S), VT(A) and VT(WS) are explained in the agreed CGK above. Simplifying slightly they represent the upper edge of the window, the lower edge of the window and the current permitted size of the window.

ii) At the start of transmission VT(S) and VT(A) are both zero.

iii) VT(WS) can be changed by higher layers or at the request of the receiver. There was a modest dispute about how often a change at the request of the receiver would happen, but I accept Mr Kubota’s evidence that it would be reasonably often.

iv) As is also explained above in relation to the CGK, the 4096 and the mod 4096 are both there to cater for the fact that the PDU sequence numbers in UMTS wrap around once they reach 4095.

v) The +1 is there so that the equation relates to the next PDU to be sent.

221. For reasons I have already touched on in relation to construction of “counting”, and on the basis of my conclusions there, the assessment of J with each PDU sent is not “counting” and does not involve counting:

i) The equation gives a percentage, not a number of PDUs.

ii) VT(S) is not a counter. It is a state variable denoting the number of the next PDU to be sent and is included in the PDU to identify it. It will generally increment with each PDU sent (except when it wraps round) but that does not make it a counter.

iii) Likewise, VT(A) is not a counter. It does not even increment with PDU transmission but changes when PDUs are ACK’d.

iv) Nor is VT(S)-VT(A) a counter of PDUs transmitted. It is the occupancy of the buffer.

v) The use of the modulo arithmetic emphasises that VT(S) is not a counter since it drops back to zero when it exceeds 4095.

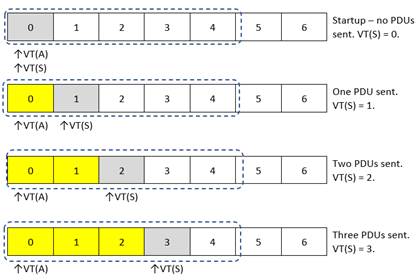

234. I start with a section from Apple’s opening skeleton which includes one of Mr Boué-Lahorgue’s figures, with some explanation that uses the abbreviations “MBL1” and “MBL2” for Mr Boué-Lahorgue’s reports (of course, Apple’s skeleton is not evidence whereas Mr Boué-Lahorgue’s report is):

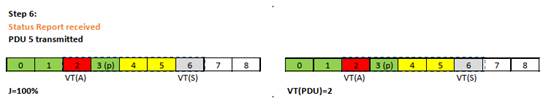

116. MBL1 para 124 at page 37 explains the operation using this diagram.

117. In the above example, for the top row J = 20% (0 unacknowledged PDUs, 1 grey PDU to be transmitted, window size 5, therefore 20% window occupancy). The following rows represent J = 40%, 60%, 80%. A poll is then triggered at 80%, and after the status report is received acknowledging all the yellow PDUs, J reverts to 20% again. The term (VT(S)-VT(A)) resets to zero.

236. Paragraphs 118 and 119 of Apple’s skeleton then included the following:

118. J therefore tracks window occupancy, and it does so by counting the transmitted PDUs which are being held in the sliding window. The term (VT(S)-VT(A)) in the formula for J functions as a counter of the PDUs in the transmission window, in which VT(S) increments as each new PDU is sent. It could not work if it was not counting them out. See again the diagram above, and that at Mr Boué-Lahorgue2 para 65 (showing behaviour at startup):

119. As MBL2 para 65 says of the above figure:

‘The variable VT(S) which is incorporated in the expression for “J” used by the UMTS window-based mechanism is unquestionably a counter. It is initialised as zero and thereafter it is incremented each time a PDU is transmitted for the first time. It therefore counts all transmitted PDUs, as and when they are sent.’

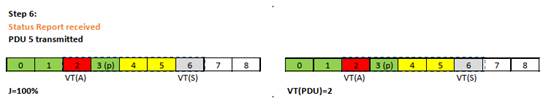

241. If any PDUs are NACK’d in a status report then the counter-based mechanism will still have reset to zero once it reached the threshold, since it always does that. But the windows-based mechanism will not see VT(S)-VT(A) go to zero because they will be separated by at least the NACK’d PDUs lodged in the window, and nor will the “as if” reset happen, since, as Mr Boué-Lahorgue put it in paragraph 23 of his second report:

“23. In the case where a PDU in the transmission window has instead been NACKed, the two counts may become out of step since VT(A) cannot move forward as shown at Step 6 above. While the counter-based mechanism will then start counting from the PDU after the PDU that triggered the poll, the window-based mechanism would start further back, and count all PDUs from VT(A), the lower edge of the transmission window as shown below:

24. It can therefore be seen that while both mechanisms are intended to track sequence number use, the window-based method more accurately reflects the occupancy of the transmission window (and therefore the sequence numbers in use), whereas the PDU counter-based one sometimes gives an approximation. In practice, the threshold parameters for each of these triggers would be set with sufficient margins to allow for the retransmission of NACKed PDUs while avoiding stalling.”

244. Two other points of detail, both minor but unfavourable to Apple, so tending to make its case worse if anything, are worth mentioning:

i) There was an issue between the experts about whether a counter sets the poll bit in the next or current PDU when the threshold is met. In his second report Mr Boué-Lahorgue assumed that Mr Kubota was correct, which tended to bring the window and counter mechanisms more closely into alignment.

ii) Status reports or reports triggered by other polls will affect a windows based mechanism but not a counter based mechanism.

248. In those circumstances, claim 6 does not in itself matter. It also only arises if I am wrong about claim 1 and therefore its consideration requires the assumption that the windows based mechanism is “counting”. Since “counting” and “reset” rather go together in my reasoning, this requires some unusually difficult mental gymnastics. Briefly, I would hold that:

i) VT(S)-VT(A) reflects window occupancy on a continually adjusted and consistently calculated basis. In certain circumstances it will go abruptly to zero, but it is not a reset as I have construed that term above. It is not a discrete step distinct from the ordinary “counting”. It is perhaps loosely analogous to all the shoppers leaving at once.

ii) I have held that it is not legitimate to look at the behaviour of the method in particular circumstances and that one must look at the method itself. But if I were wrong about that too, then Apple could focus on the no-intervening-PDUs case.

iii) In the event of these multiple contingencies Apple would not need to rely on the “as if” case. But if it did I would reject the “as if” case as unreal. Any reset to a value other than zero could be characterised as being the same as a reset to zero at some earlier time.

250. This requires the assumption that I am correct in how I have construed the claims. It then requires application of the three questions from Actavis v. Lilly [2017] UKSC 48 at [66]:

i) Notwithstanding that it is not within the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent, does the variant achieve substantially the same result in substantially the same way as the invention, ie the inventive concept revealed by the patent?

ii) Would it be obvious to the person skilled in the art, reading the patent at the priority date, but knowing that the variant achieves substantially the same result as the invention, that it does so in substantially the same way as the invention?

iii) Would such a reader of the patent have concluded that the patentee nonetheless intended that strict compliance with the literal meaning of the relevant claim(s) of the patent was an essential requirement of the invention?

251. I gave reasons for allowing the amendment on day 1 of the trial. I will not repeat them all, but some key points are worth reiterating:

i) Birss LJ decided recently in Facebook v. Voxer [2021] EWHC 657 (Pat) that infringement by equivalence must be pleaded. I agree. It follows that anticipation by equivalence must be pleaded.

ii) However, there will be cases en route to trial where the pleadings have closed before the parties knew that Facebook v. Voxer would be the regime. Allowance should be made for this.

iii) There is a big difference between a fresh pleading of equivalence which raises for the first time a new and potentially disputed feature or behaviour of the alleged infringement, and one which seeks to characterise the matters already in issue as equivalent. The present case is very much the latter.

iv) Where a pleading of equivalence is put in, it must identify the claim feature(s) to which it is directed and from there answer the Actavis questions by reference to each such feature. A general pleading that equivalence will be relied on wherever purposive construction fails is not good enough. I refused Apple’s first draft of proposed amendments on that basis.

275. The essential elements of Apple’s case seemed to me to be as follows:

i) InterDigital would seem useful to a skilled addressee working on LTE.

ii) Such a skilled addressee would have in mind, because it was CGK, the Editor’s note that either a counter or a windows-based approach was to be used.

iii) The skilled addressee would see that InterDigital had opted for a windows-based approach, and that it addressed stalling from both a PDU number and memory perspective.

iv) The skilled addressee would regard InterDigital as an attractive solution.

v) The skilled addressee would regard counting and windows-based approaches as very similar, although with somewhat different pros and cons.

vi) Whether to use a counter or a windows-based approach was really just a matter of taste and some in the art preferred counters.

vii) It would therefore be uninventive to change InterDigital to a counter-based approach.

viii) The points about attitudes to counter and window based approaches was supported by the TDoc review carried out by Mr Kubota.

299. The basic events, which are not in dispute, are as follows (I explain the process and the terms used in more detail below):

i) On 8 January 2008, Ericsson filed a US Provisional Patent Application No. 61/019746 (“the Ericsson US Provisional”).

ii) The same day, Ericsson uploaded onto 3GPP’s FTP server a technical proposal, a “TDoc”, R2-080236 (“the Ericsson TDoc”). There was a related Change Request but it makes no difference to the argument.

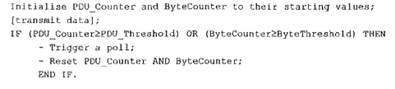

iii) The Ericsson US Provisional and the Ericsson TDoc contained very much the same information as one another, and focused on the “single mechanism” to which I have referred in dealing with the patent issues. They included the pseudocode that appears in [0045] of the Patent.

iv) At two 3GPP RAN Working Group 2 (“RAN WG2”) meetings in 2008, Ericsson’s representatives successfully made a case for the inclusion of the disclosure of the Ericsson TDoc into the LTE standard, leading to its forming part of ETSI Technical Specification TS 36.322.

v) TS36.322 was frozen (the stage 3 freeze date) on 11 December 2008.

vi) Ericsson did not mention the existence of the Ericsson US Provisional at the RAN WG2 meetings and did not declare it to ETSI until 20 May 2010.

300. Apple’s case that this creates a proprietary estoppel takes two forms (this is a very brief summary of arguments that have many nuances):

i) First, it makes what it calls its “no-IPR” case, which is that ETSI and/or members of RAN WG2 were under an assurance that Ericsson had no IPR over the Ericsson TDoc, as a result of which a chance was lost for them to seek an alternative, unpatented solution. I will refer to “IPR” and “IP” in this judgment generally, although in fact it is only patents and patent applications, not other forms of intellectual property, that are relevant.

ii) Second, and as a fallback, it says that there was a “loss of process”, such that even if there was no likelihood of the assurance making any difference in terms of a non-patented solution being sought or found, ETSI’s rules and procedures were not followed, and that is enough.

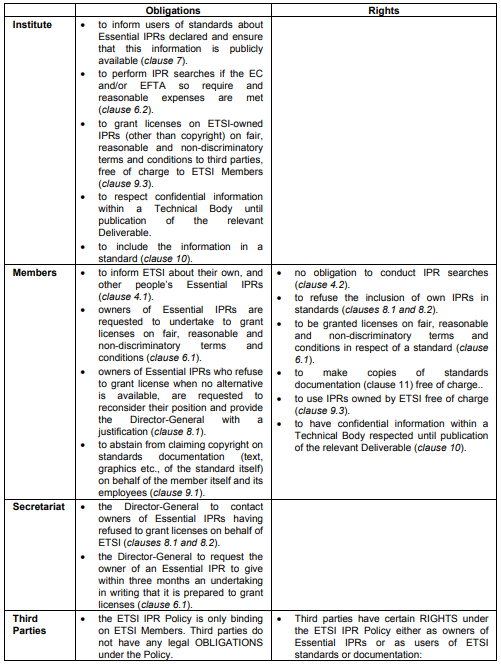

302. Part of Apple’s case, which occupied a very large proportion of the time at trial, was that Ericsson’s omission to reveal the Ericsson US Provisional by declaring it to ETSI, prior to the standard being frozen, was a breach of Clause 4.1 of ETSI’s IPR Policy, which is subject to French law and has contractual force between Ericsson and ETSI. Clause 4.1 is as follows:

“… each MEMBER shall use its reasonable endeavours, in particular during the development of a STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION where it participates, to inform ETSI of ESSENTIAL IPRs in a timely fashion. In particular, a MEMBER submitting a technical proposal for a STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION shall, on a bona fide basis, draw the attention of ETSI to any of that MEMBER’s IPR which might be ESSENTIAL if that proposal is adopted.”

309. Against this background, I have to consider the following matters, which I summarise in broad headings and not overlooking the very numerous sub-issues raised by the parties:

i) The relevant law of proprietary estoppel.

ii) What is the relevant French law applicable to Clause 4.1.

iii) The general history and arrangement of ETSI and 3GPP. It is almost entirely uncontroversial.

iv) How WGs functioned. There were some disputed aspects of this but they reduced as the trial went on.

v) The operation of the ETSI declaration process. This was also disputed to a minor degree.

vi) The history of how (a) ETSI’s rules and (b) its members’ approach to declaring IP developed, and how they stood in 2008.

vii) What Clause 4.1 requires and whether there was a breach of it.

viii) Whether the elements of proprietary estoppel are made out and whether the no-IPR or loss of process arguments succeed.

334. The parties agreed that unconscionability has a role in proprietary estoppel in addition to the three main elements, but does not found an estoppel on its own. Thus in Yeoman’s Row v. Cobbe, Lord Scott said this:

“16. […] My Lords, unconscionability of conduct may well lead to a remedy but, in my opinion, proprietary estoppel cannot be the route to it unless the ingredients for a proprietary estoppel are present. These ingredients should include, in principle, a proprietary claim made by a claimant and an answer to that claim based on some fact, or some point of mixed fact and law, that the person against whom the claim is made can be estopped from asserting. To treat a “proprietary estoppel equity” as requiring neither a proprietary claim by the claimant nor an estoppel against the defendant but simply unconscionable behaviour is, in my respectful opinion, a recipe for confusion.”

335. And to like effect, Lord Walker said:

“46. Equitable estoppel is a flexible doctrine which the Court can use, in appropriate circumstances, to prevent injustice caused by the vagaries and inconstancy of human nature. But it is not a sort of joker or wild card to be used whenever the Court disapproves of the conduct of a litigant who seems to have the law on his side. Flexible though it is, the doctrine must be formulated and applied in a disciplined and principled way. Certainty is important in property transactions. As Deane J said in the High Court of Australia in Muschinski v. Dodds (1985) 160 CLR 583, 615–616,

‘Under the law of [Australia]—as, I venture to think, under the present law of England—proprietary rights fall to be governed by principles of law and not by some mix of judicial discretion, subjective views about which party ‘ought to win’ and ‘the formless void of individual moral opinion’ [references omitted].”

336. It has been stressed by the Courts on a number of occasions that the individual elements of proprietary estoppel cannot be assessed in isolation. For example, in Gillett v. Holt, Walker LJ (as he then was) said at 225:

“This judgment considers the relevant principles of law, and the judge's application of them to the facts which he found, in much the same order as the appellant's notice of appeal and skeleton argument. But although the judgment is, for convenience, divided into several sections with headings which give a rough indication of the subject matter, it is important to note at the outset that the doctrine of proprietary estoppel cannot be treated as subdivided into three or four watertight compartments. Both sides are agreed on that, and in the course of the oral argument in this court it repeatedly became apparent that the quality of the relevant assurances may influence the issue of reliance, that reliance and detriment are often intertwined, and that whether there is a distinct need for a "mutual understanding" may depend on how the other elements are formulated and understood. Moreover the fundamental principle that equity is concerned to prevent unconscionable conduct permeates all the elements of the doctrine. In the end the court must look at the matter in the round.”

338. There have been attempts over the years to organize proprietary estoppel into different categories (acquiescence-, assurance- or promise-based in particular). In Mohammed v. Gomez, the Privy Council considered these analyses. Lord Carnwath reviewed the comments of Lord Walker in Thorner v. Major [2009] UKHL 18 (in particular those at paragraph 29, quoted above), before commenting:

“26. In the light of that discussion, the Board doubts how far it is possible or useful in the context of proprietary estoppel to draw fine distinctions between different categories. It is true that such issues seem to have attracted lively academic debate (see e.g. the references in Snell's Equity 33rd ed (2014), para 12-033). However, as Lord Walker makes clear, once one has moved beyond claims based on specific contractual rights, there may be no clear division between the nature and quality of any alleged verbal assurances, and the conduct of the respective parties in response. Depending on the factual context acquiescence may be seen as one aspect of assurance.

27. To similar effect is his earlier judgment in Jennings v Rice where he underlined the dangers of "over-simplification":

‘The need to search for the right principles cannot be avoided. But it is unlikely to be a short or simple search, because (as appears from both the English and the Australian authorities) proprietary estoppel can apply in a wide variety of factual situations, and any summary formula is likely to prove to be an over-simplification. The cases show a wide range of variation in both of the main elements, that is the quality of the assurances which give rise to the claimant's expectations and the extent of the claimant's detrimental reliance on the assurances. The doctrine applies only if these elements, in combination, make it unconscionable for the person giving the assurances (whom I will call the benefactor, although that may not always be an appropriate label) to go back on them.’ (para 44)”

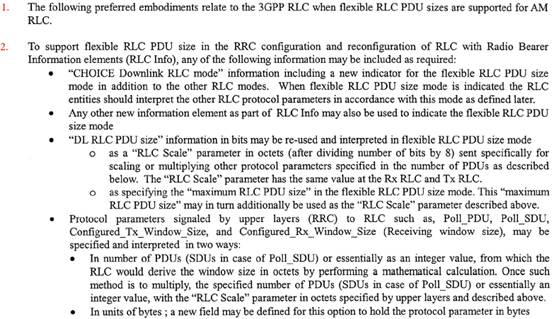

341. Optis sought to rely on this to argue that the only positive duty on Ericsson can have been under Clause 4.1, so that if Apple failed on that argument, it must fail altogether. However, Lord Wilberforce went on to explain what he meant by “duty”:

“The necessity for this duty, particularly with regard to silence or omission, has been stated in many authoritative judgments too well known to need complete citation, for they were comprehensively reviewed by Lord Wright in Mercantile Bank of India Ltd. v. Central Bank of India Ltd. [1938] AC 287. Lord Wright says there, at p. 304:

‘the existence of a duty is essential, and this is peculiarly so in the case of an omission. . . . The duty may be, in the words of Blackburn J. [in Swan v. North British Australasian Co. Ltd., 2 H. & C. 175, 182] 'to the general public of whom the person is one.' There is a breach of the duty if the person estopped [which I take to mean "sought to be estopped"] has not used due precautions to avert the risk.’"

My Lords, I think that the test of duty is one which can safely be applied so long as it is understood what we mean. I have no wish to denigrate a word which, to modern lawyers, has become so talismanic, so much a universal solvent of all problems, as the word "duty," but I think that there is a danger in some contexts, of which this may be one, of bringing in with it some of the accretions which it has gained—proximity, propinquity, foreseeability—which may be useful, or at least unavoidable in other contexts. What I think we are looking for here is an answer to the question whether, having regard to the situation in which the relevant transaction occurred, as known to both parties, a reasonable man, in the position of the "acquirer" of the property, would expect the "owner" acting honestly and responsibly, if he claimed any title in the property, to take steps to make that claim known to, and discoverable by, the "acquirer" and whether, in the face of an omission to do so, the "acquirer" could reasonably assume that no such title was claimed.”

346. In Gillett v. Holt, the claimant spent his life working on the defendant’s farm. The defendant made a number of promises and assurances that the claimant and his wife would inherit the farm upon his death. When the relationships between the parties soured, and Mr Holt created a new will without provision for the Gilletts, Mr Gillett sought equitable relief. In relation to detriment, Walker LJ said (at 232):

“The overwhelming weight of authority shows that detriment is required. But the authorities also show that it is not a narrow or technical concept. The detriment need not consist of the expenditure of money or other quantifiable financial detriment, so long as it is something substantial. The requirement must be approached as part of a broad inquiry as to whether repudiation of an assurance is or is not unconscionable in all the circumstances.

There are some helpful observations about the requirement for detriment in the judgment of Slade LJ in Jones v Watkins 26 November 1987. There must be sufficient causal link between the assurance relied on and the detriment asserted. The issue of detriment must be judged at the moment when the person who has given the assurance seeks to go back on it. Whether the detriment is sufficiently substantial is to be tested by whether it would be unjust or inequitable to allow the assurance to be disregarded— that is, again, the essential test of unconscionability. The detriment alleged must be pleaded and proved.”

347. After considering further authorities on the issue of detriment, Walker LJ considered whether the Gilletts had suffered a detriment. He held that they had, and among the detriments they had suffered was the loss of an opportunity to “better themselves”. At 234-235, he said:

“It is entirely a matter of conjecture what the future might have held for the Gilletts if in 1975 Mr Holt had (instead of what he actually said) told the Gilletts frankly that his present intention was to make a will in their favour, but that he was not bound by that and that they should not count their chickens before they were hatched. Had they decided to move on, they might have done no better. They might, as Mr Martin urged on us, have found themselves working for a less generous employer. The fact is that they relied on Mr Holt's assurance, because they thought he was a man of his word, and so they deprived themselves of the opportunity of trying to better themselves in other ways. Although the judge's view, after seeing and hearing Mr and Mrs Gillett, was that detriment was not established, I find myself driven to the conclusion that it was amply established. I think that the judge must have taken too narrowly financial a view of the requirement for detriment, as his reference [1998] 3 All ER 917, 936 to "the balance of advantage and disadvantage" suggests. Mr Gillett and his wife devoted the best years of their lives to working for Mr Holt and his company, showing loyalty and devotion to his business interests, his social life and his personal wishes, on the strength of clear and repeated assurances of testamentary benefits”.

349. Apple also relied on Habberfield v. Habberfield [2019] EWCA Civ 890, where a daughter worked on her parents’ farm for thirty years. The father assured his daughter (subject to certain qualifications, which for the purposes of this judgment are not relevant) that when he could no longer manage the business, it would be passed to her. As a result of those assurances, Ms Habberfield did not consider setting up a farming business elsewhere, even when a nearby farm became available for rent. In considering whether the judge had erred in failing to give credit for the benefits Ms Habberfield had received while working on the farm, Lewison LJ said:

“47. There are two reasons why I do not consider that this demonstrates any error on the judge’s part. First, the exercise upon which he was embarked was a broad judgmental discretion. Second, his finding was that only part of the detriment was quantifiable. The main detriment that Lucy suffered was that she had “positioned her working life” on Frank and Jane’s assurances. That detriment was incapable of reduction to pounds and pence: compare Gillett v Holt [2001] Ch 210 at 234-5. The judge so found at [225].

48. Mr Wilson next argued that in evaluating the detriment the judge had not taken account of the fact that this was not a case in which Lucy had made life-changing decisions. The main detriment was financial in nature; and the judge had been able to quantify that. Lucy had always wanted to be a dairy farmer; and had always wanted to farm at Woodrow. She had not given up any other opportunity; and when the farm at Taunton did come up for tender in 2006, Lucy and Stuart’s putative bid would have been unsuccessful. But in my judgment, it is not possible to recreate an alternative life for Lucy in a world without the assurances. As Lord Walker said in Thorner v Major at [65]:

‘But it is unprofitable, in view of the retrospective nature of the assessment which the doctrine of proprietary estoppel requires, to speculate on what might have been.’

49. Moreover, to the extent that it matters, the judge’s findings at [123] were that it was the assurances that “kept her at Woodrow;” at [157] that part of the detriment was her commitment to Woodrow “rather than going elsewhere”; and at [207] that if the assurances had not been given, most likely “she would have gone elsewhere, probably sometime in the 1990s”. She would have sought a farming tenancy elsewhere. I do not consider that we can go behind those findings of fact”.

355. At the PTR, I was asked to make an Order that there be no oral evidence on French law, hence no cross-examination. I made the Order; this approach has become common, at least in intellectual property cases, where it is anticipated that the cross-examination would consist merely of putting to the experts written materials which the Court could just read itself. It is done in the expectation that the parties will, at trial and for the purposes of pre-reading, put the Court in the position that it would be if there was cross-examination, by pointing out the key foreign law materials and the arguments on them; in my experience this works well when the parties put in the work to do this. However, I made no formal direction at the PTR about it, although I did raise, and give directions about, the mechanics of agreed translations, which the parties had not tackled.

377. Paragraphs 9 and 11 of the ALMFLI said:

“9. There is no single approach for proving the common intent of the parties when interpreting a contract in accordance with the common intent of the parties. When doing so the Court may have regards to inter alia the following:

a. The evidence of the actual intentions of the parties;

b. The purpose and intended effect of the contract;

c. The pre- and post-contractual behaviour of the parties;

d. The wording of the contract as a whole;

e. Any documentary evidence which might shed light on the common intention of the parties (including, but not limited to, negotiation documents and other similar proposals, both between the parties and between one of the parties and other third parties);

f. Previous agreements between the parties.

This is not materially in dispute.

…

11. The relevance and weight to be attributed to each factor is a matter for the trial judge.”

425. I make the following findings about WGs’ operation and meetings:

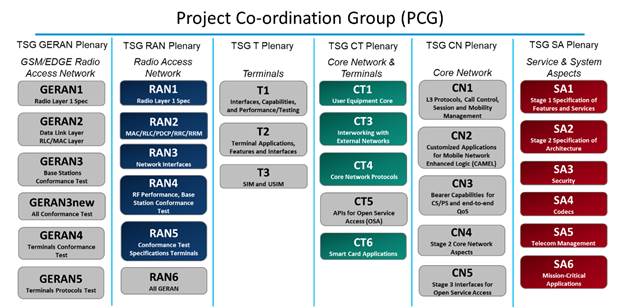

i) WGs operate by consensus. This means that proposals made in TDocs are debated and refined until there is no sustained objection. It may seem remarkable that so many people can reach this level of agreement on such complex subjects, especially given that they are commercial competitors, but that is what happens. It is an extraordinary achievement that this level of agreement is achieved time and again, over the enormous scope of the standards.

ii) WG discussions almost never touch on intellectual property matters. It is not just that raising such matters does not happen: it is regarded as positively not allowable because of competition concerns if WG members were to be seen to be making agreements about IP. In a tiny number of instances identified in these proceedings where IP was mentioned (usually in the email reflectors) it was quickly deprecated, and stopped. The instances were so few that I think they can be ignored altogether. As I have mentioned in connection with his assessment as a witness, Mr Rodermund’s report said that IP was discussed sometimes, but he retreated from that in cross-examination more or less entirely.

iii) WG meetings involve intense preparation and there are very many TDocs to consider. By way of example, at one of the meetings where the Ericsson TDoc was presented, there were 663 TDocs submitted. About 10 or 20 proposals might be made for a single feature.

iv) A technical proposal might generally take about three or four months to get into the relevant specification under discussion.

426. I find that a large proportion of the inventions underlying potentially essential patents were made close in time to WG meetings when the engineers involved focused on the specific technical problems relevant to the parts of the standard they were working on. It is impossible and unnecessary to put a precise figure to the proportion of declared essential patents that fell into this category. In such circumstances:

i) It was common to file a patent application in very similar terms to the TDoc just before provision of the TDoc to a WG. Otherwise, the TDoc would anticipate any later application.

ii) In such cases, the patent application would most probably be unpublished at the freeze date.

iii) It was common for the inventor to participate at the WG, since they understood the invention and could advocate for it.

iv) It would be easy for the employer of the inventor to know that the TDoc and the patent application were connected and for the same thing, although making the link would require the cooperation of the engineers and the patent department.

443. I find that there was in fact no practice of WG participants checking to see whether TDoc proposals up for discussion in a forthcoming meeting were or might be covered by IP. The evidence is overwhelming, but in particular:

i) There is not a single example in the evidence before me of it ever happening.

ii) Apple had a strong incentive to find examples if they existed (not only for this case but also the Texas litigation), and the resources to do so. The amounts at stake would have justified the effort. I infer that it has looked and failed to find any. There have been many WG participants over the years and while many still work for their companies and owe continuing duties of confidentiality, others will have moved on or retired and would be available as witnesses (as Mr Rodermund and Ms Dwyer are).

iii) There was no point in WG participants looking for declarations in the ETSI database as a starting point for such a check, since participants nearly all declared after the freeze date.

iv) Declarations that were submitted before the freeze date might well not be on the database until after the freeze date because of the reflection period.

v) Even to the extent declarations of IP were made by TDoc proposers in time for them to be available for study prior to a WG meeting, matching a declaration to a TDoc would have been very difficult. This would be even more difficult (if possible at all) for unpublished patent applications. Reasons included the fact that declarations mostly did not include the “illustrative specific part” field. Mr Rodermund suggested that it might be possible to match dates of patent applications, TDocs and declarations, but that would depend on declarations being made at the same time as TDocs, and even if they were I think his idea, which is untested, was very implausible and would have been extremely laborious with little reasonable expectation of good or reliable results.

vi) There was no incentive to do any such checks, since even if IP were identified, a WG participant who did so would not be able to make an argument that the presence of IP was a reason to reject a TDoc, or to discuss such a notion with other participants. All he or she could do would be to make arguments against the technical merits of the TDoc, which would then be accepted or rejected based on its technical merit in any case.

vii) The run up to WG meetings was a very busy time for all concerned with a huge number of TDocs to assess for their technical merit. That work, and not IP checks, was the priority.

viii) The overall goal of WG participants was to arrive at the best technical solution.

ix) It was a fact of life that ETSI standards, because they were innovative in many respects, would be subject to IP. There was a strong incentive to make sure that essential IP was subject to effective FRAND undertakings (although this was not the job of the WGs), but very little motivation, if any, to make marginal changes to how many patents were essential

444. I have already mentioned the lack of incentive to check whether TDocs were covered by IP because even if they were, or were thought to be, a WG participant could not raise the topic as such, but only advocate for a different technical solution on technical grounds. As to this:

i) Apple laid extremely heavy emphasis on some passages of the cross-examination of Ms Dwyer where, it submitted, she had accepted that individual members of ETSI who sent delegates to WGs “can” take licensing costs into account in their selection of the best technical solution. She said that “cost might be considered”. She said that where information on costs was available “it may influence companies’ positions, and, yes, ultimately that may influence the outcome.” This was on day 4, pages 579-589.

ii) In view of Apple’s heavy reliance, I have re-read this evidence with particular care. In my view she was not accepting any such influence on the outcome as being realistic; at most she was accepting that it was theoretically possible.

iii) Ms Dwyer cogently made the point that since WGs work by consensus, it would not be practical to oppose what was in fact the best technical solution in this way, let alone in the sustained fashion necessary to block a consensus.

iv) The questioning also muddled up, or was confusing over, licensing costs with whether patent applications might exist.

v) As with the issue of whether WG participants tried to check TDocs against IP, there is no example in the case of a WG participant advancing a technical argument against a TDoc in order to inhibit its adoption for IP reasons. Of course this would not be obvious on the face of what was said in the meeting, but for reasons given above, witnesses who had seen it done by their own organisations could have been sought.

445. For the reasons already given, I do not think that any thought would have been given by RAN WG2 participants to whether or not there was likely to be IPR associated with the Ericsson TDoc. But if there had been, I find that in the circumstances of:

i) RAN WG2 being a “patent heavy” working group;

ii) Ericsson being a well-known innovator, patent filer and WG participant;

iii) The TDoc for the application which ultimately led to the Patent being presented as a solution for a new problem arising in LTE;

any WG participant who had thought about whether Ericsson was likely to have IPR over the TDoc, would conclude that from those circumstances, and regardless of whether Ericsson had made a declaration, that it was very likely, such IPR being in the form of a patent application. This is what Ms Dwyer said, and Mr Rodermund essentially agreed, merely qualifying his answer by saying that not all proposals had associated IPR.

450. My view is that there was no relevant assurance and that WG members did not make decisions about TDocs based on IPR. However, I make the following factual findings in case I turn out to be wrong:

i) WG members would, if they considered it, have thought that Motorola was likely to be covered by a patent application. The evidence on this was from Mr Boué-Lahorgue and from Ms Dwyer and I found the latter’s evidence more convincing.

ii) No Motorola application has even been identified but that does not mean that there was not one. An application covering it might well have been abandoned before publication.

iii) There is no evidence that Motorola was as good a solution as that of the Patent and it probably was not; it just presented a menu of possible alternatives.

iv) Motorola was actually an LTE TDoc presented to RAN WG2. If it was the best solution it probably would therefore have been considered and adopted.

v) InterDigital was a UMTS proposal and therefore would not have come to the attention of RAN WG2 for LTE.

vi) Similarly, it would have been thought, had the matter been considered, that InterDigital was probably covered by a patent application (InterDigital being a vigorous applicant for patent protection).

vii) Pani is a PCT and therefore obviously subject to IP but in any event was not published in time to be considered at the relevant meetings.

viii) Overall, I draw the inference that the Patent’s solution was the best of anything of which RAN WG2 for this LTE release was aware, or could reasonably have been aware.

456. As to the utility of the materials:

i) I consider it key to decide what ETSI’s intentions were. Statements of desire of individual members can have little weight. For example, Optis sought to rely on specific proposals by Italtel and Fujitsu in 1994; I have no way of knowing if they represented the general views of ETSI members.

ii) Proposals that were not adopted are of only limited use individually, although there is modest force in Optis’ point that various tougher provisions (in the sense of hard-edged rules, or rules backed by sanctions) were proposed but not accepted. More relevant are changes that did take place, and the reasons for them.

iii) Competition law theory in itself is of limited significance. The way in which ETSI fed its understanding of competition law into the ETSI IPR Policy is more important, and its discussions with the Director of the European Commission’s Competition Directorate-General (“DG Comp”) in and around 2005 are important for the same reason.

iv) Discussions and documents that were explored in the written expert evidence are more useful than those that were put in only in cross-examination materials at trial.

457. As to the key points from the history, I consider them to be:

i) There was a 1993 Interim IP Policy and an Associated IPR Undertaking. It was unpopular with patent-owning members for a variety of reasons. For present purposes, the main point is that it had a fixed 180-day time limit from a standard’s adoption for a patentee to identify essential IPR and remove it from what was in general a licence by default scheme.

ii) Following complaints from members, pressure from the European Commission, and US Government lobbying, a revised Interim IPR Policy was adopted by the General Assembly of ETSI in 1994. I set out key provisions below. Its Clause 4.1 had the same structure as the current Clause 4.1 the subject of these proceeding, subject to changes I discuss below.

iii) In 1997 the 1994 Interim IPR Policy was made definitive.

iv) In 1998 ETSI signed up to the 3GPP Partnership Agreement.

v) In 2002/2003 there was a review (the “Ad Hoc Group Review” or “AHG Review”) of the IPR Policy. One reason was that the Chair of an ETSI technical committee had written to the Director General proposing changes, which included that documents presented to Working Groups (i.e. including TDocs) should include a pro forma statement of IPR content, and that members should have to renounce IPRs that were not declared in a timely fashion. These were not accepted. I refer to some key events during the review.

vi) Following the AHG Review, the 2004 IPR Guide was published. I refer to sections of this below.

vii) Starting at the end of 2004 but mainly taking place in 2005, there was a discussion between DG Comp and ETSI over the IPR Policy and in particular clause 4.1. DG Comp disliked the vagueness of the “timely” requirement in the first sentence of clause 4.1. ETSI resisted this change, and “timely” was retained, although moved around in the sentence; however, the words “in particular during the development of a STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION” were added. I refer to some key events below.

viii) This led to a new version of the IPR Guide being produced, with a new section 4.5, written by DG Comp. I set this out below.

463. Clause 3 set out the policy objectives of the ETSI IPR Policy:

“3. Policy Objectives

3.1 STANDARDS and TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS shall be based on solutions which best meet the technical objectives of the European telecommunications sector, as defined by the General Assembly. In order to further this objective the ETSI IPR POLICY seeks to reduce the risk to ETSI, MEMBERS, and others applying ETSI STANDARDS and TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS, that investment in the preparation, adoption and application of STANDARDS could be wasted as a result of an ESSENTIAL IPR for a STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION being unavailable. In achieving this objective, the ETSI IPR POLICY seeks a balance between the needs of standardization for public use in the field of telecommunications and the rights of the owners of IPRs.

3.2 IPR holders whether members of ETSI and their AFFILIATES or third parties, should be adequately and fairly rewarded for the use of their IPRs in the implementation of STANDARDS and TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS.

3.3 ETSI shall take reasonable measures to ensure, as far as possible, that its activities which relate to the preparation, adoption and application of STANDARDS and TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS, enable STANDARDS and TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS to be available to potential users in accordance with the general principles of standardization.”

466. Clause 6 set out the rules in respect of the availability of FRAND licences:

“6. Availability of Licences

6.1 When an ESSENTIAL IPR relating to a particular STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION is brought to the attention of ETSI, the Director-General of ETSI shall immediately request the owner to give within three months an undertaking in writing that it is prepared to grant irrevocable licences on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms and conditions under such IPR to at least the following extent:

• MANUFACTURE, including the right to make or have made customized components and sub-systems to the licensee's own design for use in MANUFACTURE;

• sell, lease, or otherwise dispose of EQUIPMENT so MANUFACTURED;

• repair, use, or operate EQUIPMENT; and

• use METHODS.

The above undertaking may be made subject to the condition that those who seek licences agree to reciprocate.

6.2 At the request of the European Commission and/or EFTA, initially for a specific STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION or a class of STANDARDS/TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS, ETSI shall arrange to have carried out in a competent and timely manner an investigation including an IPR search, with the objective of ascertaining whether IPRs exist or are likely to exist which may be or may become ESSENTIAL to a proposed STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS and the possible terms and conditions of licences for such IPRs. This shall be subject to the European Commission and/or EFTA meeting all reasonable expenses of such an investigation, in accordance with detailed arrangements to be worked out with the European Commission and/or EFTA prior to the investigation being undertaken.”

467. Clause 8 set out the procedure that should be followed if a member notified ETSI that they are not prepared to grant a licence of an essential IPR:

“8. Non-availability of Licences

8.1 MEMBERS' refusal to license

8.1.1 Where a MEMBER notifies ETSI that it is not prepared to license an IPR in respect of a STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION, the General Assembly shall review the requirement for that STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION and satisfy itself that a viable alternative technology is available for the STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION which:

• is not blocked by that IPR; and

• satisfies ETSI's requirements.

8.1.2 Where, in the opinion of the General Assembly, no such viable alternative technology exists, work on the STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION shall cease, and the Director-General of ETSI shall request that MEMBER to reconsider its position. If the MEMBER decides not to withdraw its refusal to license the IPR, it shall inform the Director-General of ETSI of its decision and provide a written explanation of its reasons for refusing to license that IPR, within three months of its receipt of the Director-General's request.

The Director-General shall then send the MEMBER's explanation together with relevant extracts from the minutes of the General Assembly to the ETSI Counsellors for their consideration.

8.2 Non-availability of licences from third parties

Where, in respect of a STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION, ETSI becomes aware that licences are not available from a third party in accordance with Clause 6.1 above, that STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION shall be referred to the DirectorGeneral of ETSI for further consideration in accordance with the following procedure:

i) The Director-General shall request full supporting details from any MEMBER who has complained that licences are not available in accordance with Clause 6.1 above.

ii) The Director-General shall write to the IPR owner concerned for an explanation and request that licences be granted according to Clause 6.1 above.

iii) Where the IPR owner refuses the Director-General's request or does not answer the letter within three months, the Director-General shall inform the General Assembly. A vote shall be taken in the General Assembly on an individual weighted basis to immediately refer the STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION to the relevant COMMITTEE to modify it so that the IPR is no longer ESSENTIAL.

iv) Where the vote in the General Assembly does not succeed, then the General Assembly shall, where appropriate, consult the ETSI Counsellors with a view to finding a solution to the problem. In parallel, the General Assembly may request appropriate MEMBERS to use their good offices to find a solution to the problem.

v) Where (iv) does not lead to a solution, then the General Assembly shall request the European Commission to see what further action may be appropriate, including nonrecognition of the STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION in question.

In carrying out the foregoing procedure due account shall be taken of the interest of the enterprises that have invested in the implementation of the STANDARD or TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION in question.”

474. Section 4.1 of the Ad Hoc Group Report discussed the timely disclosure of essential IPRs:

“4.1 Timely disclosure of essential IPRs

It seems obvious, that if essential IPRs in an ETSI Standard are not disclosed in a timely, manner there might be severe consequences. But, more surprisingly, there are also difficulties in making timely disclosures. These issues are summarised below.

A lack of timely disclosure (or the lack of an available undertaking) would delay commencement and hence delay completion of negotiations on the detail of licenses, which may delay market entry. If this occurs, the resulting delay in the implementation of a product may place a company in a difficult situation. This happens even if licenses are ultimately available on ETSI IPR policy terms. In particular, there is uncertainty over the outcome of negotiations over the details of the licenses which has to be resolved before a product can be launched.

[…]

The main task of a Technical Body is the search for the best technical solution and that the existence of essential IPRs is not a barrier. Non-disclosure of essential IPR in a specific technical solution is not a problem for the Technical Body unless, ultimately, licenses are not available under FRAND conditions (see section 4.4). If this happens, then a standard could become blocked by the nonavailability of IPR licenses on terms that meet ETSI’s IPR policy. The committee would then be asked to re-write the standard.

Furthermore, ETSI also needs to deal with timely disclosure in the context of a publicly available specification or other document offered to ETSI for publication.

The concept “timely” is already documented, in terms of points where disclosures could or should be made:

• On formal submission of a technical solution,

• On completion of the first stable draft of the Standard,

• On working group approval of a draft Standard,

• On Technical Body approval of a draft Standard.

It was agreed that a formal of definition "timely" would be a change to the policy, so the aim of the recommendations here is to refine the advice to Members and to promote the achievement of “timely disclosure” rather than to define the concept.”

477. Recommendations 1 to 6 were proposed in respect of the issues discussed at section 4.1 of the Ad Hoc Group Report:

“Recommendation 1 (addressing the definition of timely)

The IPR ad hoc group noted that there should be no further definition of "timely" since this would constitute a "change to the policy".

However, the IPR ad hoc group recommends that ETSI Members should implement mechanisms to improve timeliness and deal as far as possible with the uncertainties. Such mechanisms could include guidance on best practice to ensure timeliness.”

“Recommendation 2 (addressing the improvement of timeliness of essential IPR disclosures)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends that, in order to set down the basis for early disclosure by ETSI Members of their alleged-essential IPRs, ETSI Members having IPR portfolios should improve their internal IPR co-ordination processes to ensure, as far as possible, that their standards body attendees are aware of any alleged-essential IPR the company may have (related to the on-going work on a particular ETSI Standard or Technical Specification), that they understand their obligations, and that they know how to discharge them.”

“Recommendation 3 (addressing the improvement of timeliness of essential IPR disclosures)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends a review of the ETSI Seminar material on Members’ obligations under the IPR policy with respect to Recommendation 2. This will help to ensure that new standards body attendees understand their obligations, and know how to discharge them.”

“Recommendation 4 (addressing the improvement of timeliness of essential IPR disclosures)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends that the TB Chairman's Guide on IPR should encourage Members to use general IPR undertakings/declarations and then provide or refine detailed IPR disclosures as more information becomes available.”

“Recommendation 5 (addressing the improvement of timeliness of essential IPR disclosures)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends that ETSI should co-operate with other SDOs on improving the timeliness of disclosures relating to essential or potentially essential IPRs.”

“Recommendation 6 (dealing with the uncertainty of timeliness)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends that the TB Chairman's Guide on IPR should include a note that those Members developing products based on standards where there may be essential IPRs, but there is uncertainty, have mechanisms they can use to minimize their risk. As a non-exclusive example, a Member might wish to put in place financial contingency, based on their assessment of “reasonable” (a separate issue in this discussion) against the possibility that further/additional license fees might become payable.”

478. Section 4.2 of the Ad Hoc Group Report discussed the issues arising from late IPR declarations:

“4.2 Late IPR Information Statement and Licensing Undertaking/Declaration

Generally, there is only a problem with late IPR declarations if the patent is not available at all for licensing, or is not available on "Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND)" terms.

Mechanisms for making late declarations to ETSI need to be clarified (Note: At present declarations - late or otherwise - can be made to the ETSI Secretariat at any time). Time limits (3 / 6 months) also need to be considered.

ETSI Members dissatisfied with the consequences of other people’s late IPR declarations can and should have the right to appeal to the GA - e.g. to have the contents of the relevant standard / specification changed.

There is a need to work closely with other SDOs to look more carefully at the procedures (if any) for identifying and declaring any relevant essential IPRs when their text is being referenced / copied into ETSI standards and specifications.”

480. Recommendations 7 and 9 then proposed the following amendments in respect of these issues:

“Recommendation 7 (Identifying where ETSI has a problem arising from "late disclosures" in IPRs)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends that the Chairman's (or Delegate's) Guide on IPR should include a note that:

"...the main problems for ETSI as a standards body which arise from "late disclosures" include:

- Licenses for the Patents disclosed late and are not available at all, or,

- Licenses for the Patents disclosed late are available, but are not on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms, i.e. the company is unwilling to make a ‘FRAND’ undertaking/declaration.

If the above problems cannot be satisfactorily resolved, then ETSI has to change the standard, which in some extreme cases could even include the need to start again with the development of that standard....".”

“Recommendation 9 (concerning the update of Standard or Technical Specification)

The IPR ad hoc group recommends that Published Standards or Technical Specifications should not be redrafted because a change on the essentiality of an IPR arises unless the required undertaking/declaration has not been provided within the three month period foreseen under section 6.1 of the IPR Policy, or has been refused. Any IPR changes should be entered into the ETSI IPR Database, showing the date of the entry.”

481. Section 4.12 discussed “out of scope issues” (that is, issues which were discussed but upon which no consensus was reached):

“4.12 Out of Scope issues

The GA is invited to note the following issues which were discussed, but upon which no consensus was reached. Furthermore, they were ruled out-of-scope:

• The requirement that ETSI Members should grant licenses on a royalty free basis when it is proven that the IPR information statement and licensing undertaking/declaration were intentionally delayed.

• The proposal to recognise the value of technical contributions from ETSI Members that have freely given their expertise and technology to develop the Standards or Technical Specifications when negotiating related IPR licenses.

Any Member interested in one of these issues is free to submit appropriate contributions to the General Assembly.”

485. Article 1.1 lay down the purpose of the ETSI IPR Policy:

“1.1 What is the Purpose of the IPR Policy?

The purpose of the ETSI IPR Policy is to facilitate the standards making process within ETSI. In complying with the Policy the Technical Bodies should not become involved in legal discussion on IPR matters. The main characteristics of the Policy can be simplified as follows:

● Members are fully entitled to hold and benefit from any IPRs which they may own, including the right to refuse the granting of licenses.

● Standards and Technical Specifications shall be based on solutions which best meet the technical objectives of ETSI.

● In achieving this objective, the ETSI IPR Policy seeks a balance between the needs of standardization for public use in the field of telecommunications and the rights of the owners of IPRs.

● The IPR Policy seeks to reduce the risk that investment in the preparation, adoption and application of standards could be wasted as a result of an Essential IPR for a standard or technical specification being unavailable.

● Therefore, the knowledge of the existence of Essential IPRs is required as early as possible within the standards making process, especially in the case where licenses are not available under fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms and conditions.

The ETSI IPR Policy defines the rights and obligations for ETSI as an Institute, for its Members and for the Secretariat.

The Policy is intended to ensure that IPRs are identified in sufficient time to avoid wasting effort on the elaboration of a Deliverable which could subsequently be blocked by an Essential IPR.”

488. The first part of Article 2 set out the importance of timely disclosures of essential IPRs:

“2. Importance of timely disclosure of Essential IPRs

The main problems for ETSI as a standards body which may arise from "late disclosures" include:

● Licenses for Patents which have been disclosed late and are not available at all, or,

● Licenses for Patents which have been disclosed late and which are available, but not on Fair, Reasonable and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) terms, i.e. the company is unwilling to make a ‘FRAND’ undertaking/licensing declaration.

If the above problems cannot be satisfactorily resolved, then ETSI has to change the standard, which in some extreme cases could even include the need to start again with the development of that standard.

NOTE 1: Definitions for “Timeliness” or “Timely” cannot be agreed because such definitions would constitute a "change to the Policy".

NOTE 2: The following description of Intentional Delay has been noted:

"Intentional Delay" has arisen when it can be demonstrated that an ETSI Member has deliberately withheld IPR disclosures significantly beyond what would be expected from normal considerations of "Timeliness".

This description of ‘Intentional Delay’ should be interpreted in a way that is consistent with the current ETSI IPR Policy. In complying with the requirements of timeliness under section 4.1 of the IPR Policy, Members are recommended to make IPR disclosures at the earliest possible time following their becoming aware of IPRs which may be Essential.

NOTE 3: "Intentional Delay", where proven, should be treated as a breach of the IPR Policy (clause 14 of the ETSI IPR Policy) and can be sanctioned by the General Assembly.”

489. Article 2.1.1 was about responding to Calls for IPRs:

“2.1.1 Responding to Calls for IPRs performed in Technical Body meetings

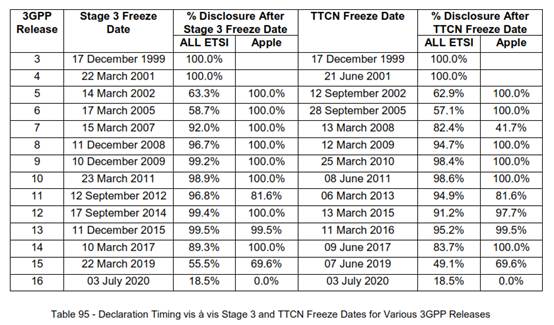

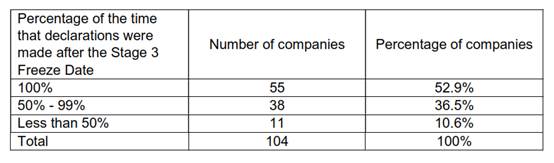

Members participating in Technical Bodies should respond at the earliest possible time to the Call for IPRs performed by Technical Body Chairmen at the beginning of each meeting, based on the working knowledge of their participants.