An Chúirt Uachtarach

The Supreme Court

O’Donnell J

McKechnie J

MacMenamin J

Charleton J

O’Malley J

Supreme Court appeal number: S:AP:IE:2020:000064

[2021] IESC 7

High Court record number 2018/872JR

[2020] IEHC 222

Special Criminal Court Bill number:

Between

Kevin Braney

Accused/Appellant

- and -

Ireland and the Attorney General

Respondent

- and -

The Director of Public Prosecutions

Notice Party

Judgment of Mr Justice Peter Charleton delivered on Friday 12 February 2021

1. Kevin Braney stands convicted that on 2 August 2017 he was a member of the self-styled Irish Republican Army or Óglaigh na hÉireann. He challenges the validity of s 30(3) of the Offences Against the State Act 1939, the police power on which he was arrested and questioned. This authorises the gardaí to arrest a suspect on reasonable suspicion of certain very serious offences. These are offences scheduled under the 1939 Act. Since the Criminal Justice Act 1984, under general arrest powers applying to all offences carrying a possible maximum penalty of 5 years imprisonment or more, an arrestee’s detention for questioning in a Garda station must also be authorised as necessary for the investigation of the offence by another Garda officer in charge of the station; s4(2) of the 1984 Act. Section 30 of the 1939 Act does not require this. Initially, a person arrested under s 30(3) may be held and questioned for up to 24 hours. Section 30(3) also enables the initial 24 hours of detention upon arrest to be extended for a further 24 hours on the authorisation of a Chief Superintendent, who is not necessarily a Garda officer independent of the enquiry which led to the suspect’s arrest. It is contended by Kevin Braney that, under the Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights, for a detention for investigation or questioning to be valid, a second opinion, from the Garda in charge of the station, as to the validity of the arrest and the necessity for detention, is required.

2. Further, arguing on the basis of what is claimed to be an analogous police power, that of the search of a home, the accused asserts, invoking Damache v DPP & Others [2012] IESC 11, [2012] 2 IR 266, that, apart from emergency, since only a judge or an uninvolved police officer may issue a search warrant, similarly only a judge or an uninvolved police officer can extend the initial 24 hours of detention by a further 24 hours. Here, it might immediately be noted that detention outside s 30 arrest is extended by a police officer: thereby a 6 hour detention can become a 12 hour detention upon arrest; s4(3)(b) of the 1984 Act. In so far as there is a difference between the procedures for arrest and detention as between s 30 and other forms of arrest and detention for different offences, this is argued by Kevin Braney to infringe Article 40.1 of the Constitution whereby all “citizens … as human persons” are to be “held equal before the law”. This difference in procedures is also argued to be incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

3. In The People (DPP) v Quilligan and O’Reilly (No 3) [1993] 2 IR 305, this Court has already held that the provisions of s 30 of the 1939 Act were not repugnant to the Constitution. The accused asks for this authority to be reviewed. The standard whereby this Court might overturn precedent thus requires analysis. Finally, issues as to inferences from failure to answer pertinent questions relevant to a charge of membership of an unlawful organisation, a scheduled offence under the 1939 Act, are also brought into contention by Kevin Braney and are asserted to be unconstitutional and incompatible with the Convention.

4. By determination dated 30 July 2020, this court granted leave to appeal from the ruling of the High Court, Barr J [2020] IEHC 222, dismissing the claims of unconstitutionality and incompatibility; [2020] IESCDET 95. This was done mainly on the basis of the binding precedent in Quilligan and O’Reilly. The issues raised in the application for leave were regarded as being of general public importance and because of the binding precedent governing any appeal, this in part constituted an exceptional but not automatic circumstance justifying a direct appeal to this Court from the High Court.

Approach to facts

5. It was by a process of judicial review as to the constitutionality and compatibility of s 30 that this case reached the High Court, and not by an appeal to the Court of Appeal from the conviction for a criminal offence. Following a two-week trial, Kevin Braney was convicted before the Special Criminal Court on 30 May 2018 of membership of an unlawful organisation, styling itself the Irish Republican Army or Óglaigh na hÉireann. The Defence Forces of Ireland are properly called Óglaigh na hÉireann; military.ie. Other organisations claiming to be the ‘Army’ of the Irish Republic and usurping the legitimate army of the State, for terrorist purposes, are prescribed organisations under the Offences Against the State Act 1939. Membership of such is an offence carrying a potential maximum penalty of eight years imprisonment; s21(2)(b) of the 1939 Act, as amended. Kevin Braney was imprisoned, following a written ruling of the Special Criminal Court finding him guilty of that offence, for four years and six months.

6. In light of the ordinarily binding nature of facts found by the High Court when an appeal is brought, the circumstances whereby Kevin Braney mounts this challenge to the constitutionality of s 30(3) of the 1939 Act are properly to be derived from the judgment of Barr J; Ryanair v Billigfluege.de GmbH and others [2015] IESC 11 as to affidavit evidence and an appellant bearing the burden of proof that facts found were unreasonable and Doyle v Banville [2012] IESC 25 and Hay v O’Grady [1992] 1 IR 210 as to the binding nature of a finding on oral evidence.

Background facts

7. Initially, the High Court set out the event which was central to the charge that on 2 August 2017 Kevin Braney was a member of the self-styled Irish Republican Army or Óglaigh na hÉireann. Barr J set out that he was arrested by a police officer on that day, the day to which the charge relates, and that he was detained initially on foot of that arrest for 24 hours and that the detention was extended for a further 24 hours by Chief Superintendent Thomas Maguire in accordance with the impugned section. The circumstances prior to the arrest and as a basis for the findings of the Special Criminal Court at Kevin Braney’s criminal trial were set out by Barr J thus:

8. The background to that arrest arose in the following circumstances: the applicant had been seen on a number of occasions prior to 13th July, 2017 in the company of, and in conversation with, men who had been convicted of various offences contrary to the 1939 Act. In particular, the applicant had been present as a member of the public at a sentence hearing before the Special Criminal Court held on 6th February, 2017 when one Patrick Brennan was being sentenced for possession of explosives and detonators. Evidence was given that in the course of the sentence hearing, the court put it to Mr. Brennan that he would need to undertake to renounce subversive activities if he wished to avail of a suspension of two years of the proposed sentence of seven years. At the applicant’s trial, a Sergeant Boyce gave evidence that when this was put to Mr. Brennan, he looked over at the applicant and then declined to make any indication that he would renounce subversive activities and accordingly the sentence of seven years stood.

9. The pivotal evidence at the trial, concerned the applicant’s movements and activities on 13th July, 2017. Evidence was given by a member of the Garda Surveillance Unit that at 13.02 hours he observed the applicant, and his co-accused meeting at [a shopping centre] in Dublin. Later at approx. 19.38 hours, the car owned by the co-accused, Mr. Maguire, was observed driving through [a toll bridge near Dublin]. When the Garda conveyed that message over the radio system he subsequently received an instruction to go to [an address near the city]. There he observed Mr. Maguire’s car parked in [an ordinary housing estate] and [two men] enter the driveway of a house. He saw the two men at the front door of the house. That was at 19.57 hours. He was not in a position to maintain observation after that time until 20.05 hours. At that time, he observed the driveway of the house where he had seen the applicant and Mr. Maguire, but they were no longer there. Mr. Maguire’s car was gone from [the location]. The house which they had visited was [the home of a witness].

10. [That witness] gave the critical evidence at the trial. In summary, he stated that he had worked for a particular man as [an operative]. He made a statement to Gardaí that on 13th July, 2017 at approx. 19.30/20.00 hours he was in the bathroom when he heard heavy knocking coming through the front door and window. When he came out of the bathroom he saw two people at the door. He stated that it was obvious from the way that they were knocking that there were not there as he put it “to read the meter”. He went upstairs because they had left and he could see two people walking away from the house. He believed that when they observed him in the window, they turned around and came back to speak with him. He asked if he could help them and they asked for his name, which he gave to them. They said that they wanted to speak to him and he said that he could hear them from where he was, so that they could speak to him at the window.

11. [The witness] said that the men said “We don’t want to shout it all over the street. You have a claim in against Nicholas Duffy”. [The witness] replied that he had a claim in against the insurance. One of the men said “Nicholas Duffy does an awful lot of work for the Republicans of Portlaoise Prison. So, what you’re going to do is you are going to ring your solicitor in the morning, you’re going to drop the case because it’s fraudulent”. [The witness] stated that he replied “It’s fraudulent, is it?” and one of the men replied “Yeah, it is. We are the IRA, and the next time we come down to see you, we’ll be coming down to shoot you”. He stated that after that the men walked away across the road. After the incident [the gardaí were contacted].

8. The High Court also analysed the judgment of the Special Criminal Court in convicting Kevin Braney. Barr J set out the reasoning for his conviction at paragraph 15 of the High Court judgment:

On 30th May 2018, the Special Criminal Court delivered its judgment, wherein it convicted the applicant of an offence contrary to s.21 of the 1939 Act, in particular membership of a prescribed organisation, in particular membership of the organisation styling itself Óglaigh na hÉireann/IRA. The court reached its verdict on the basis of four strands of evidence being: the belief evidence given by C/Superintendent Maguire given pursuant to the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act 1972; evidence of association between the applicant and members of the IRA; conduct evidence in relation to his actions on 12th and 13th July, 2017 and inferences from his failure to respond to material questions put to him after the invocation of certain statutory inference provisions, in particular the provisions of s.2 of the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act, 1998. Certain inferences were also drawn from his refusal to answer certain questions which had been put to him pursuant to s.19 of the Criminal Justice Act 1984. On conviction the applicant was sentenced by the Special Criminal Court to 4½ years imprisonment.

9. The Chief Superintendent who extended the initial 24-hour detention of the applicant was Chief Superintendent Thomas Maguire. Some emphasis is placed on the fact that he also gave evidence, as he was legally empowered so to do, of his belief that Kevin Braney was at the relevant time a member of the self-styled Irish Republican Army.

10. Thus, there were four strands to the conviction: the opinion of the police officer at that rank, association with other members of the illegal organisation, conduct as to the threats, and inferences from his failure to answer questions material to the charge; such inferences being made by legislative authority under s 2 of the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act 1998.

11. Kevin Braney contends that the inference from failure to answer questions evidence was drawn from the period after the detention was extended. Therefore, he argues that some of the evidence upon which he was convicted was inadmissible at trial, supposing that the extension from the initial 24 hour period following arrest had been invalidly extended by Chief Superintendent Maguire. Other aspects of the evidence, including the opinion evidence, the association evidence and the conduct on the relevant date would remain untouched.

Offences Against the State Act

12. The Offences Against the State Act 1939, the impugned legislation, was specifically designed as an anti-terrorism measure. A brief reference to the history of the Offences Against the State Act 1939 should be made. In January 1939, the self-styled IRA/Óglaigh na hÉireann called on Great Britain to withdraw from the six counties of Northern Ireland and threatened action should such a declaration not be made within four days. When the demand evoked no response, a terror campaign was unleashed in England. This caused, pursuant to the so-called ‘S-Plan’ of bombing organised by the unlawful organisation’s ‘Director of Chemicals’, explosions that killed a fish porter in Manchester, another fatality in a left-luggage facility at King’s Cross railway station in London, and the deaths of five people in Coventry, ranging from a schoolboy to a man in his eighties. In all there were about 120 terror explosions that year; Robert Fisk, In Time of War: Ireland, Ulster and the price of neutrality 1939-1940 (London, 1983) 72-75. The Bill of February 1939, that became the 1939 Act, outlawed actions subversive of the exclusive authority of the State, including usurping or obstructing the functions of government, interfering with the military or public service, carrying out unauthorised military exercises, setting up secret societies within the military or public service, distributing or printing seditious materials, unlawfully administering oaths and proscribing certain organisations and making membership of same an offence. Explosives offences and firearms offences were already on the statute book and these were scheduled to the Act so that the powers of arrest and detention set out in s 30 would apply to an extended range of terrorist type crimes. The Special Criminal Court was also set up to judge scheduled cases by the written verdict of three judges, subject to appeal in the ordinary way, as in other criminal cases, it having been adjudged pursuant to Article 38 of the Constitution that “the ordinary courts” were “inadequate to secure the effective administration of justice, and the preservation of public peace and order”. The Special Criminal Court operates precisely the same fundamental rules of evidence and procedural safeguards as all other courts.

13. The originally scheduled offences, enabling arrest under s 30 and trial in the Special Criminal Court did not include, and have since not encompassed, such crimes as sexual violence, drugs, homicide, theft and fraud, but centred around explosives and firearms offences and those crimes created by the 1939 legislation itself. The original Act has been much amended; twice in 1940, in 1941, in 1942, in 1972, in 1985, and in 1998: the latter after the terrorist bombing with multiple fatalities in Omagh on 15 August of that year and introducing novel offences of directing or training or possession of articles, perhaps not already covered by criminal law inchoate offence theory. The schedule has been amended to remove malicious damage offences and to keep up with the changes to the legislation itself. The currently scheduled offences are set out in Appendix II to this judgment.

Universal detention safeguards

14. Arrest expressly for the purpose of questioning was possible up to 1984 only under s 30 of the Offences Against the State Act 1939. Prior to that time, there was no power for the detention of a person for the purposes of questioning or taking samples, for instance blood or DNA or hair samples; People (Director of Public Prosecutions) v O’Loughlin [1979] IR 85. Since, however, the Judges’ Rules of 1912 required the administration of a caution as to the right to silence where a suspect had been arrested and, since such a caution was also required where a police officer had decided to charge a suspect with an offence, despite rule 1 stating that nothing prevented a police officer making enquiries of anyone, it is clear that as between arrest and bringing the suspect before a judge for charge, there was an interval. That could be used to question the suspect, but this power was informal and depended very much on the time of arrest and the gap to the next sitting of the court which could reasonably be accessed. At common law, arrest was considered as the first formal step in the judicial stage of the criminal process; People v Shaw [1982] IR 1, 29. In that case, Walsh J made it clear that: “No person may be arrested (with or without warrant) for the purpose of interrogation or the securing of evidence from that person.” This extended to arrest for the purpose of an identification parade, formal or not; The People (Director of Public Prosecutions) v Donaghy [1988] 3 Frewen 138.

15. To supplement these limited powers, the Criminal Justice Act 1984 introduced arrest for questioning and other investigations, including: identification parades, sampling with consent or by statutory authority and questioning. This was for up to 6 hours, extendable by a senior officer to 12 hours, including overnight when questioning normally must be suspended. The nature of the change meant that the legislation incorporates safeguards to ensure the proper treatment of persons in custody. All such safeguards apply to arrested persons, whether arrested under the 1939 Act or the 1984 Act. The exception to this is that once a person is arrested under s 30 it is not necessary to check that arrest and detention with the Garda in charge of custody who under the 1984 Act must concur that the arrest and detention are reasonably necessary for the investigation of the offence. The general regulations, which have been amended several times to require, among other safeguards, interviews recorded on video, apply to all forms of arrest and detention for investigation, including s 30. These are SI No 119/1987, The Criminal Justice Act, 1984 (Treatment of Persons in Custody in Garda Síochána Stations) Regulations, 1987. An overview of the requirements applying both to persons arrested under s 30 and other arrests necessarily follows.

16. On arrest, a suspect is given a form which outlines his or her rights to a lawyer, to medical assistance, to proper treatment and to contact with family. All custody, including s 30 detention, is overseen by a Garda who is designated “member in charge” of the station. That person must open a custody record and must periodically check on the detainee to ensure proper treatment, the provision of meals, rest and pauses between interviews, sleep at night, legal assistance and if necessary any medical checks arising from any condition such as asthma or other pre-arrest issues. If any issue arises at trial, the custody officer may be called as a witness. Where under s 30, a detention is extended from 24 hours to 48 hours by a senior officer, this must be noted in the custody record as must every incident as to complaints, visits, facilities, meals, sleep, hours of questioning, any move from cell to interview room, and attendance by a solicitor. Article 7(4) of the Regulations provides:

Where a direction has been given under section 30 of the Offences against the State Act, 1939 (No. 13 of 1939), that a person be detained for a further period not exceeding twenty-four hours, the fact that the direction was given, the date and time when it was given and the name and rank of the officer who gave it shall be recorded.

17. Essentially, and solely, the difference between a s 30 arrest under the 1939 Act and an arrest under s 4 of the 1984 Act is that additional opinion, which is beyond the opinion of the arresting officer, that the detention is necessary for the investigation of the offence for which the person was arrested. Hence, Article 7(2) of the 1987 Regulations provides:

In the case of a person who is being detained in a station pursuant to section 4 of the Act the member in charge at the time of the person's arrival at the station shall, when authorising the detention, enter in the custody record and sign the following statement:

"I have reasonable grounds for believing that the detention of (insert here the name of the person detained) is necessary for the proper investigation of the offence(s) in respect of which he/she has been arrested."

18. It requires emphasis that no one, either under s 30 or more generally for less specific offences, is entitled to arrest anyone without having reasonable grounds of suspicion as to their involvement in an offence or to continue with an arrest where during the course of investigation that suspicion dissipates. While this is cast in statutory form in relation to general arrest under the 1984 Act, the principle of minimal and justifiable interference with liberty in the form of arrest prevails throughout the law and is certainly applicable to s 30 arrests. Section 4(4) of the 1984 Act is, in this respect, declaratory of general law:

If at any time during the detention of a person pursuant to this section there are no longer reasonable grounds for suspecting that he has committed an offence to which this section applies, he shall be released from custody forthwith unless his detention is authorised apart from this Act.

the principles set out by this court in East Donegal Co-Operative v. Attorney General [1970] I.R. 317, must be applied to the statutory powers of detention. It does not follow that because the section permits of detention for up to eight weeks in the aggregate, the proposed deportee may necessarily be detained for that period if circumstances change or new facts come to light which indicate that such detention is unnecessary.

20. Therefore, even where the initial detention is lawful it may become unlawful because new facts come to light which make the continuation of a detention no longer based on reasonable suspicion. Should that new fact be such as to dissolve the reasonable suspicion in the mind of the arresting officer, the detention must cease.

Suspicion must be reasonable

21. An arrested person is entitled to know why that infringement of the general right to be at liberty is being effected; Re Ó Laighléis [1960] IR 93. Our system does not support undermining the suspect through secrecy as to what is under investigation; Farrelly v Devally [1998] 4 IR 76. Nor does the law permit indeterminate detention but instead all suspects will receive legal advice and will know through the officer in charge of the Garda station what the maximum period of arrest for investigation is. No arrest of any kind can take place unless there is a reasonable suspicion in the mind of the arresting officer that a criminal offence, one categorised in law as enabling arrest, has been committed and that the person to be arrested has committed that offence. Circularity tends to undermine any attempt to define what a reasonable suspicion is since it constitutes a considered decision to analyse grounds of suspicion and to test whether that on which the suspicion is based is more than a hunch but can be justified by reason. A hunch can lead to the consideration of circumstances and facts that ground a reasonable suspicion but a mere hunch without factors which would lead an ordinary and reasonable person to suspect the involvement of the person to be arrested is far from sufficient. Individual decisions have emphasised the necessity for s 30 to be construed so as to render unlawful any purported arrest under that power unless suspicion based on reasonable grounds is demonstrated. Thus in The People (DPP) v Quilligan & O’Reilly [1986] IR 495 at 507, 514-515, 520-21 this court emphasised that to found a valid arrest the suspicion of the arresting officer must be held in good faith and be “not unreasonable’’; and see The People (DPP) v Tyndall [2006] 1 IR 593, Denham J at 599-602. Citing Quilligan & O’Reilly, she emphatically ruled out any arrest unless coming within the scope of and for the powers conferred by legislation or common law and as being based on a reasonable suspicion:

Suspicion is not defined in the Act. It should be bona fide and not irrational. It is a fact to be proved by direct evidence, or it may be inferred from the circumstances. It is an essential proof. The circumstances of this case were not such as to enable a court to infer the suspicion. The learned trial judge was not entitled to conclude that the circumstances were sufficient to compel an inference that the necessary suspicion existed. If the fact of an arrest by a detective sergeant, who was an investigating officer, was sufficient from which to infer the required suspicion of the member of the Gárda Síochána, when the arrest is only valid if the member has the necessary suspicion, it would be to apply reasoning which is circular and flawed. There must be circumstances other than the arrest itself by a member of the Gárda Síochána from which the suspicion of the arresting member may be inferred. The clear words of s.30 require that the arresting member of the Gárda Síochána have a suspicion. Evidence of that suspicion may be given either by direct evidence or by indirect evidence.

22. This requirement of reasonableness is grounded in general administrative law, the presumption that no administrative or executive body could act so as to fly in the face of reason and common sense, thereby exceeding the bounds of conferred jurisdiction, becoming crystallised over time into a requirement of acting in accordance with reason, and on reasonable grounds, in all actions potentially infringing the rights of citizens. This is the general test cited, for example, in Walsh on Criminal Procedure (2nd edition, Roundhall, 2016) at 4.77 where, commenting on what is “not unreasonable”, it is stated:

Presumably, it does not mean that the suspicion must be an objectively reasonable one, otherwise the learned judge would surely have stated quite simply that it must be a reasonable suspicion or a suspicion based on reasonable grounds. At the same time it clearly signifies the need for something more than a mere honest suspicion in the mind of the arresting officer. Hogan and Walker [ - Political Violence and The Law in Ireland, 1989, 203-204] suggest that it signifies the administrative law test of reasonableness that is generally applied in a judicial review of the exercise of discretionary powers. In effect, the judge would be looking for the existence of facts upon which a police officer could reasonably have formed a suspicion that the person to be arrested had committed the offence in question. It may be that the judge himself or even another police officer might not necessarily have formed the same suspicion. That, however, would not matter so long as the facts were such that it would not have been unreasonable for the police officer concerned to have formed the suspicion. Hogan and Walker go on to suggest that the difference between this test and that of “reasonable suspicion” which applies to most arrest powers may not be very great as the Irish courts now insist on the existence of objective evidence to justify the exercise of discretionary powers. In practice, the Irish courts have repeatedly applied an objective standard for the suspicion in s.30 without yet feeling the need to determine whether that is the conventional objective standard or some modified version.

23. A reasonable suspicion is not concerned with what evidence might be admitted or excluded at trial, save that the ordinary principle of relevance in terms of one fact proving, tending to prove, or being capable of inferring the existence of another applies. Rather, it is capable of being founded on hearsay, circumstance, inference, record and conduct, the proof of a fact other than by direct testimony and the prior convictions of an accused generally being inadmissible at trial; DPP (Walsh) v Cash [2007] IEHC 108. In CRH plc v Competition and Consumer Protection Commission [2018] 1 IR 521 at paragraph 236, in the context of search and seizure of emails from a computer, but analysing the concept of reasonable suspicion as it applies in arrest, extension of detention and search warrant powers, Charleton J offered the following analysis of the relevant authorities:

In terms of the ordinary construction of the powers of search, a warrant is issuable by the District Court on reasonable suspicion that “evidence of, or relating to” an offence under the 2002 Act “is to be found in any place”; thereafter the officers of the Commission have a month to “enter and search the place” and to “exercise all or any of the powers conferred on an authorised officer under this section.” A reasonable suspicion is one founded on some ground which, if subsequently challenged, will show that the person arresting, issuing the warrant or extending the detention of the accused acted reasonably; see Glanville Williams, “Arrest for Felony at Common Law” [1954] Crim LR 408. A reasonable suspicion can be based on hearsay evidence or the discovery of a false alibi; Hussein v Chong Fook Kam [1970] AC 942: or on information offered by an informer who is adjudged reliable; Lister v Perryman [1870] LR 4 HL 521, Isaacs v Brand (1817) 2 Stark 167, The People (DPP) v Reddan [1995] 3 IR 560. A suspicion communicated to a garda by a superior can be sufficient to constitute a reasonable suspicion, as may a suspicion communicated from one official to another, which is enough to leave that other individual in a state of reasonably suspecting; The People (DPP) v McCaffrey [1986] ILRM 687. The fact that a suspect is later acquitted does not mean that there was not a reasonable suspicion to ground either an arrest or a search. It is accepted by the European Court of Human Rights that “the existence of a reasonable suspicion is to be assessed at the time of issuing the search warrant”; Robathin v Austria (App. No. 30457/06) (Unreported, European Court of Human Rights, 3rd October 2012) at para. 36. Having information before a judge of the District Court whereby he or she may reasonably suspect the potential presence of information on a premises founds the warrant. The standard being applied here is such as might be familiar from civil or criminal practice. But issuing a search warrant is not to be confounded with any analogy with the criminal trial process. That is not the task. Facts are not being found: facts are being gathered. It necessarily follows that what is involved is an exercise in the pursuit of what is potential, essentially an exercise which may yield no information or limited information. It is of the nature of a criminal enquiry that a warrant may authorise an intrusion into someone’s privacy to little or no effect. This is of the nature of what is required in the course of information gathering and a negative result does not upset the validity of what was done if, after the event, information that may serve towards displacing the presumption of innocence happens not to have been gleaned. The power to issue the search warrant, therefore, does not in this instance inform the nature of the powers that may be exercised pursuant to it.

24. Most fundamental to the protection of all arrested persons is the floor of rights which provides for clarity as to reasons for arrest, no arrest without reasonable suspicion and that once a suspicion dissipates while liberty is temporarily suspended by reason of arrest, through for instance the suspect demonstrating a sound factual basis or by other independent enquiry, the liberty of the suspect must be restored. This floor of rights applies as stringently to s 30 arrest under the 1939 Act as to arrest under the general power under the 1984 Act and to other myriad powers of arrest at common law and by various disparate statutes. This constitutes a solid floor upon which other entitlements or other statutory mechanisms for the administration of arrest have been built, among other legislation by the 1984 Act. The fact, however, that other methods or different safeguards inform arrests and detentions different to the very serious matters targeted by the 1939 Act does not mean that constitutional infirmity or invidious discrimination attach to the earlier specialised legislation. In itself, criminal law and criminal procedure are made up of a patchwork of measures: a new menace presents itself, people being stabbed with syringes or harassment or bullying through social media, the law responds and a penalty is set. This does not mean that potential penalties are to be scrutinised for their conformity with earlier legislation, for instance as to wounding or as to besetting, or that the necessarily individual and event-based response to the development of crime is to become homogenised. Ultimately, the safeguard which presents to all of this is the duty of the courts to find and impose a penalty, just as in tort law, the existing remedies are to be adapted to new situations. In the award of damages or injunctive relief, or in settling on an appropriate punishment, justice is the guide and constitutional infirmity does not arise due to piecemeal responses unless it excludes in its entirety, and through any reasonable interpretation of legislation, the possibility that the judicial arm of government may not arrive at a just result.

25. In that regard, it is argued on behalf of Kevin Braney that false arrest is not amenable to remedy. This is not so since false imprisonment is a tort entitling the victim to an award of damages. On his contention, this is insufficient since a person whose arrest continues unjustifiably, or in respect of whom the detention should never have taken place since no reasonable suspicion ever existed, has no remedy. This is not so.

Article 40.4

26. The guarantees in the Constitution are not rhetorical or lyrical but real. Every phrase in the Constitution has an imperative meaning. Article 40.4.1° provides that only through a valid law may persons be deprived of their liberty. In so declaring, a remedy is established in Article 40.4 whereby any person, not the prisoner or detainee solely or that person’s lawyer, but a member of his or her family or any interested person, may, without formality, apply to the High Court for an enquiry as to whether that person is or is not being lawfully detained:

1° No citizen shall be deprived of his personal liberty save in accordance with law.

2° Upon complaint being made by or on behalf of any person to the High Court or any judge thereof alleging that such person is being unlawfully detained, the High Court and any and every judge thereof to whom such complaint is made shall forthwith enquire into the said complaint and may order the person in whose custody such person is detained to produce the body of such person before the High Court on a named day and to certify in writing the grounds of his detention, and the High Court shall, upon the body of such person being produced before that Court and after giving the person in whose custody he is detained an opportunity of justifying the detention, order the release of such person from such detention unless satisfied that he is being detained in accordance with the law.

3° Where the body of a person alleged to be unlawfully detained is produced before the High Court in pursuance of an order in that behalf made under this section and that Court is satisfied that such person is being detained in accordance with a law but that such law is invalid having regard to the provisions of this Constitution, the High Court shall refer the question of the validity of such law to the Court of Appeal by way of case stated and may, at the time of such reference or at any time thereafter, allow the said person to be at liberty on such bail and subject to such conditions as the High Court shall fix until the Court of Appeal has determined the question so referred to it.

4° The High Court before which the body of a person alleged to be unlawfully detained is to be produced in pursuance of an order in that behalf made under this section shall, if the President of the High Court or, if he is not available, the senior judge of that Court who is available so directs in respect of any particular case, consist of three judges and shall, in every other case, consist of one judge only.

5° Nothing in this section, however, shall be invoked to prohibit, control, or interfere with any act of the Defence Forces during the existence of a state of war or armed rebellion.

6° Provision may be made by law for the refusal of bail by a court to a person charged with a serious offence where it is reasonably considered necessary to prevent the commission of a serious offence by that person.

27. In other countries, this procedural recourse to the courts in assertion of the right to liberty is called the right to habeas corpus. Such cases proceed on a matter of urgency and without the need for the filing of documents; a simple oral application to any judge of the High Court suffices. There are no procedures since the constitutional imperative of liberty transcends all rules of court. There is a solemn duty on the High Court to make that enquiry and to pronounce under Article 40.4.3° if that person “is being detained in accordance with law” and, under Article 40.4.2° in all cases, to “order the release of such person from such detention unless satisfied that he is being detained in accordance with law.” Further see Gerard Hogan and Gerry Whyte, Kelly: The Irish Constitution, (5th edition, Bloomsbury Professional, Dublin, 2018), at [7.4.366]. This is not an empty formula, as is contended for by Kevin Braney. In State (Trimbole) v The Governor of Mountjoy Prison [1985]I.R. 550 a suspect wanted in Australia appeared in Ireland but in the absence of an extradition treaty or arrangement between the two countries. The applicant was arrested on suspicion of possessing firearms. On an application under the ancient remedy given constitutional form in Article 40.4, the High Court rejected the explanation for the arrest holding instead it to be a device to enable the time for such arrangements to be made. Under prior scheduling to the 1939 Act, enabling arrest under s 30, malicious damage was scheduled.

28. Other reported cases are informative. In Dempsey v Member in charge of Tallaght Garda Station and others [2011] IEHC 257 the applicant’s solicitor had made enquiries of the police and did not receive a satisfactory answer as to the basis for his arrest. The applicant was physically produced to the High Court where the State informed the court that it was not proposed to detain the applicant in custody any further. In Finnegan v Member in Charge (Santry Garda Station) [2006] 4 IR 62 an inquiry was granted under Article 40.4 where the Applicant had his detention extended under s 30 by a District Court Judge in circumstances where at the time the order of extension was made the initial 48 hours of detention had expired by approximately 25 minutes. The applicant was released. In Moloney v Member in Charge of Terenure Garda Station [2002] 2 ILRM 149 the applicant was arrested under s 30 for firearms offences. His detention was extended for a period of 24 hours. During the detention he was questioned in respect of the offence of murder in connection with which he had two months previously been arrested under s 4 of the Criminal Justice Act 1984. The applicant brought an application under Article 40.4 of the Constitution of Ireland. The court was satisfied, on the evidence, that the arrest of the Applicant was bona fide. There was an issue raised as to whether the arrest was in fact a re-arrest in prohibited circumstances. The application was dismissed. Where the crime to be addressed, however, was in reality not a scheduled offence, and murder was not and is not a scheduled offence, but damage to a weapon used to kill, or cattle maiming, is used as a colourable device to enable arrest for what is in reality murder, that renders any arrest unlawful and triggers the appropriate declaration under Article 40.4; DPP v Howley [1989] ILRM 629. There this Court examined circumstances where the accused had been arrested for the scheduled offence of malicious damage offence of maiming cattle, but was in reality was being arrested for a murder that had taken place some months later. This device was condemned as unlawful, Walsh J stating at 634:

Therefore what the cases established is that when an arrest for a scheduled offence effected under s. 30 of the Offences Against the State Act 1939, not only must the arresting Garda have the necessary reasonable suspicion concerning the particular offence in question, but that in fact there must be a genuine desire and intent to pursue the investigation of that offence or suspected offence and that the arrest must not simply be a colourable device to enable a person to be detained in pursuit of some other alleged offence.

29. Throughout any detention, the accused has a right to legal advice, including while being questioned. In The People (DPP) v Gormley and White [2014] 2 IR 591, the Supreme Court held that basic fairness required that an interview should not take place when a request for a lawyer has been made and before that lawyer is available. No interview of the suspect can be carried out save where that person has the benefit of having spoken to a lawyer; The People (DPP) v Doyle [2018] IR 1. Pursuant to this State’s obligations to the European Convention on Human Rights, during interview, unless a suspect decides to waive that entitlement, a lawyer will be present; Application 51979/17 Doyle v Ireland judgment of 23 May 2019. Thus, at all times during interview there will be a lawyer present for the detained person. Upon arrival in custody, a printed notice in several languages is given to the arrestee detailing rights to legal advice and all detainees know that a custody record detailing every significant event chronologically will be kept. As the Europe Court of Human Rights emphasised in its analysis of Irish law, the safeguards around detention are marked by a requirement of fairness, that interviews be video recorded, that there be no unlawful inducement or any form of intimidation and that legal assistance operate as a counterbalance to the deprivation of liberty. Upon analysis of the particular manner in which fairness dominates the potential for the taking of any confession statement and the safeguards surrounding custody, that court held:

100. In conclusion, the Court recalls that its role is not to adjudicate in the abstract or to harmonise the various legal systems, but to establish safeguards to ensure that the proceedings followed in each case comply with the requirements of a fair trial, having regard to the specific circumstances of each accused (see Beuze, cited above, § 148.).

101. In the present case it is important to stress that while a majority of the Supreme Court, which engaged extensively with the Court’s case-law on Article 6, was correct in concluding that where there have been procedural defects at pre-trial stage, the primary concern of the domestic courts at trial stage and on appeal must be the overall fairness of the criminal proceedings, it failed to recognize that the right of an accused to have access to a lawyer extended to having that lawyer physically present during police interviews.

102. The Court finds that, in the circumstances of the present case, notwithstanding the very strict scrutiny that must be applied where, as here, there are no compelling reasons to justify a restriction of the accused’s right of access to a lawyer, when considered as a whole the overall fairness of the trial was not irretrievably prejudiced.

103. The foregoing considerations are sufficient to enable the Court to conclude that there has been no violation of Article 6 §§ 1 and 3 (c) of the Convention.

30. It must be recognised that these strictures as to legal advice being a central component of detention operates as a safeguard to the right to liberty. Thus, legal presence enables, if necessary, any application for scrutiny to the High Court. It is important to note also that, following the implementation of the Legal Advice Revised Scheme, someone detained under s 30 of the 1939 Act is entitled to legal aid to cover the costs of a solicitor attending an interview or interrogation parade.

Development of detention powers

31. While reference has been made to the absence of formal powers for detention for questioning from the independence of the State in 1922 up to the passing of the 1939 Act, when detention for a limited time and for a particular purpose related to offences scheduled under that legislation, confession statements were still possible but a formalisation of time periods was required. Depending on the availability of courts and a proximate sitting, the time of arrest and the willingness of lawyers to offer advice, this system lacked certainty of administration that should characterise a legal system. Hence, the reforms introduced by the 1984 Act. One of the purposes of this was to rationalise for arrest purposes the common law distinction as between crimes that were felonies and others which were classified as misdemeanours. Due to the development of criminal law, rationality could be viewed as being challenged where fraud was generally classified as a misdemeanour, but could be massive in impact, as in a major bank fraud, while theft was within the more serious classification of felony, even though it might be quite minor, as in shoplifting. Arrest could take place by a citizen on another citizen where a felony had in fact been committed, as a certain fact and not merely that this was reasonably suspected, and the citizen reasonably suspected the arrestee of the crime. An example was shoplifting but the arrested person had to be handed over to a police officer as soon as practicable. Where fraud was involved, because of the classification, no such arrest was possible. A police officer could arrest where the officer reasonably suspected the commission of a felony and that the suspect had committed such an offence. Misdemeanour powers of arrest were statutory and had developed piecemeal. In addition arrest for breach of the peace was and is possible pursuant to the common law duty of police officers to keep the peace; Thorpe v DPP [2007] 1 IR 502, DPP v O Brien [2020] IEHC 110. Arrest powers were rationalised in addition to general powers of detention by the 1984 Act by making serious crimes, ones carrying 5 years or more imprisonment, arrestable as if these were felonies, the abolition of the felony-misdemeanour distinction and the retention of existing arrest powers for lesser offences, mostly resulting from disparate statutory powers.

32. Even countries based on codes will experience the development of law whereby strictures applied to certain crimes are not found with others or whereby absolute and certain logic does not prevail from amendment to amendment of existing law or through the introduction of new laws. This does not demonstrate, necessarily, infirmity from the aspect of the protection of rights. As has been mentioned, as new situations come to light, legislatures will respond as best they can to the changes which social order, as the object of law declared in the Preamble to the Constitution, requires. Legal rules in a common law system are the products of experience; the law evolves in response to novel situations and is refined on the basis of what works best. The nature of the adversarial system means that, when courts adjudicate matters and contribute to the development of the common law, the legal rules enunciated are necessarily tailored to the arguments advanced before them and are limited in their scope to the facts of the case. The result is that different rules develop in response to different, although perhaps similar, legal questions. Similarly, the legislature responds to situations as they arise and tailor their approach to the particular offence with which they are dealing. This does not mean that there are inconsistencies in the legal system but it does mean that different offences are treated differently as a result of the policy choices underlying the relevant statutes. All systems, whether they be based on the common or civil law, differentiate in this way between different offences; coherence within a legal system does not require absolute uniformity and neither does ant principle of fairness. Not every situation calls for an identical number of hours of detention and the strictures needed in dealing with very serious crimes such as sampling or searches need not be applied across the board. Police officers cannot just take it as so if a suspect confesses to a terrorist offence. Perhaps the person was set up by members of a gang, or designated as the fall-guy or is suggestible? Everything requires officers to go out and seek cross-supportive facts or note the absence of same. This takes time. The person best placed to ensure a fair appraisal is the senior officer tasked with overseeing the extension of detention. That officer knows more than anyone else and if there is a wrong analysis, remedies under the Constitution in support of liberty are available. At a minimum, the detained suspect has legal assistance in custody.

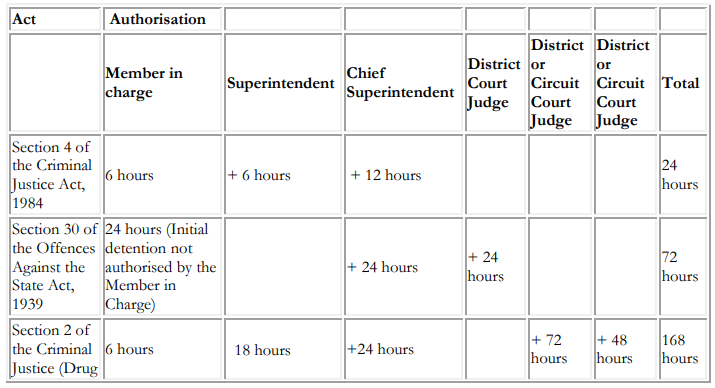

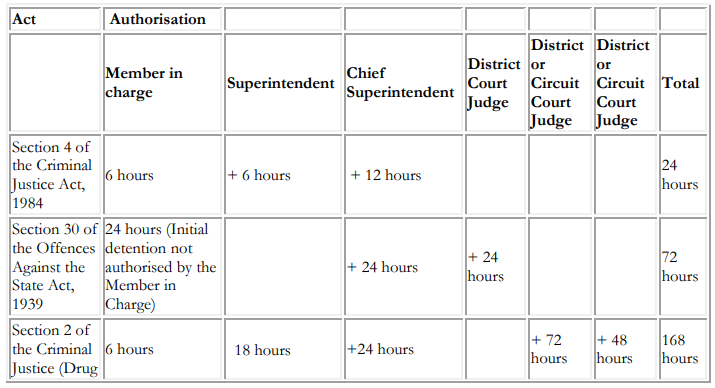

33. As the realisation of the dangers of organised crime resonated in the wake of headline incidents of perpetration, the legislature has responded. And this is surely an experience common to all countries. The criminogenic effect of drug abuse is an example of how it may be necessary to construct an individual response to a drastic social situation. Hence, there are a myriad of responses. This table gives an accurate set of legislative data as to the kind of crimes which the law has responded to, the time for detention where a suspect is so characterised, how detention may be extended, the limits thereof and when a judicial authority appointed under the Constitution is required to authorise an extension of detention:

34. As is apparent, particular safeguards as to the rank of officer, that individual’s necessarily long experience and particular training, are brought into the administration of custody as times for detention may extend. This demonstrates the care whereby the floor of rights is maintained while differing legal responses operate on that foundation. Hence, both s 30 of the 1939 Act and the general arrest powers under s 4 of the 1984 Act differ, and the nature of the general wrongs in the latter differ from the scheduled offences under the former. With the near total repeal of the Malicious Damage Act 1861, and with the passing of the Criminal Damage Act 1991, the scheduled offences to the 1939 Act are now even more clearly focused on combatting terrorism and organised crime. The provisions pertaining to arrest and detention in the statute are therefore tailored to combatting these particular offences, which necessitates a difference in approach from that under the 1984 Act. Prior to the 1991 Act it might be argued that break ins to premises or damage to property in the course of a homicide might enable s 30 as an arrest power but that can no longer be claimed. Moving the focus of this police instrument to trafficking and organised crime offences, more time for investigation may be needed and this is hardly surprising in the context of the culture of omerta which characterises criminal gang discipline. That does not mean the denial of rights since that floor of rights guaranteed by the Constitution still prevails.

Equality

35. Central to the argument made by Kevin Braney is that the extension of the detention of an arrested suspect is the same as the issue of a search warrant. If that is so, that contention runs, then the arrest of a suspect, involving as it does the temporary denial of liberty, but on a reasonable and considered basis, should somehow be equated with detention itself, with the extension of that detention and with search warrant powers. That is not so. While the doctrine of equality mandated by Article 40.1 of the Constitution seems held between polarities of those aspects of the human personality which must not be discriminated against and a wider doctrine apparently requiring all similar situations to be treated equally, the express wording focusing on the attributes of shared humanity has not been abrogated by referendum of the people: “All citizens shall, as human persons, be held equal before the law.” Hence, a reading of the case law, while emphasising human personality as a touchstone, has moved outside the confinement of personal attributes and into a search for comparators and why apparently equal situations do not call for uniform treatment. There is no imperative discoverable from any case decided by this Court whereby all situations must be resolved in law into homogeneity. One situation of non-homogeneity may be unconstitutional unless treatment is underpinned by practical reasons that do not seek to discriminate on an unfair basis that draws from prejudice or the differentiation of people on the basis of their essential attributes. As the criminal law has developed over time, and by experience of what is needed to combat distinctly different wrongs against society, differing crimes have required varying powers of investigation and while the overlapping sets of circumstances are not always entirely uniform, there is a reasoned basis underpinning those different powers which the legislature has ascribed to the police in the pursuit of attaining true social order. None of these differences set out to discriminate as between people: rather the variations in police powers are attributable to three factors: the nature of the threat to society; the need to circumscribe the temporary deprivation of liberty and privacy with safeguards; and the imperative to adequately enable an investigation towards the exclusion of the innocent and the safeguarding of society from the infinitely variable and seldom less than insidious forms of criminal activity.

36. By reason of arrest, in our system, and in most legal systems, a person is detained. In respect of other offences which are not scheduled under the 1939 Act, there is an extension possible in that detention for investigation, one mandated by a police officer of high rank, first of all, and up to 48 hours, but no further under a s 30 arrest. At the 48 hour point, s 30 detention stops. But under other forms of arrest 48 hours can be extended to up to a week made by a judge sitting in a court and hearing appropriate evidence to justify such further deprivation of liberty, one increasing the detention by 120 hours. The proofs enabling such an extension are the same as for extension by a police officer of high rank; the reasonableness of the suspicion linking the accused to the crime and the necessity for more time to enable the investigation to be thorough. Section 30 arrests stop at 48 hours and do not extend to the kind of longer-term detention for a week, 168 hours, which as the foregoing table demonstrates, applies to some very serious forms of crime outside of the offences scheduled under the 1939 Act. Search, in truth, is not an analogous police power to detention. Still, there should be a floor of rights to ensure the security of rights. But, as between those whose homes or premises are searched and those arrested for investigation, those rights are different. Furthermore, the patchwork of legislative responses in police powers cannot be expected to exactly match and nor does any principle of fundamental law require these democratic answers to crime to homogeneously coalesce.

37. Clearly, there should be safeguards for invasions of the private space, most especially that of the space where people dwell. Article 40.5 of the Constitution provides: “The dwelling of every citizen is inviolable and shall not be forcibly entered save in accordance with law.” There has to be a fundamental standard of legality. Again, the standard has to be that of reasonableness because lawful action intruding on rights to liberty implies not only compliance with the letter of the law but with justifiable human reasoning. No one can search based on a mere intuition. For legal validity, any such hunch has to be backed up by the use of rationality. Since what is involved is an administrative action affecting existing rights, and since under s 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights Act 2003, such actions are required to be Convention compliant, there is no sense in which merely intuitive excuses for an invalid search can be dressed up as reasons. Fundamentally, such an intrusion cannot be on a basis lacking reason, some excuse that flies in the face of fundamental reason and common sense offends the reasonableness standard. Invoking Damache v DPP & Others [2012] IESC 11, [2012] 2 IR 266, and correctly stating the position in our law that, apart from in an emergency, only a judge or a high-ranking police officer from outside the investigation may issue a search warrant, it is argued that only a judge or a high-ranking police officer from outside the investigation can extend the initial 24 hours of detention under s 30 by a further 24 hours. In this context, it is to be remembered that other forms of detention outside of a s 30 arrest is to be extended by a police officer: thereby a 6 hour detention can become a 12 hour detention upon arrest and so on in accordance with the table above.

38. A reasoned analysis of the nature of search demonstrates the difference between an intrusion into a physically private space and the nature of an ongoing detention for questioning or sampling. In search, there is no entitlement for a lawyer to be present; CRH plc v Competition and Consumer Protection Authority. In the aftermath of a search, in the context of a criminal trial, or through a civil action for alleged trespass, such an intrusion can be questioned. But, of the nature of a search, the protection of rights needs to be assured in advance; that there are reasonable grounds whereby, to use an oft repeated statutory formula found invariably in dispirit criminal legislation, evidence in relation to the commission of an offence may be found, at the location specified in the warrant. In itself, the warrant is not shorn of temporal connection. Since circumstances can change, thus a search warrant requires to be executed within a time limit that is invariably set by statute. It is not a case of the authorities arming themselves with a search warrant and holding it merely as a speculative weapon over an extended period; rather it is there to be used. According to the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America, “the people” have the right “to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures” and where no warrant may issue “but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized”. This may be reflected in the fundamental law of several European countries. In our Constitution, it is Article 40.5 but the protection against unreasonable search is a product of the common law.

39. Article 40.5 expresses a sensible approach to the protection of the privacy of the home, or in the original text “ionad cónaithe” whereby there is a protection by law frontloaded before an authorised intrusion. Many statutes distinguish, in that regard, between a requirement for judicial authorisation where a home is searched and where the search is of business premises. Making no comment on this, it is apparent that the Damache decision concerned the home and the need for forcible entry to have particular protection through independence of authorisation. An extended quote from that case and the judgment of Denham CJ illustrates this:

47. The procedure for obtaining a search warrant should adhere to fundamental principles encapsulating an independent decision maker, in a process which may be reviewed. The process should achieve the proportionate balance between the requirements of the common good and the protection of an individual’s rights. To these fundamental principles as to the process there may be exceptions, for example when there is an urgent matter.

48. Analysis and application of such fundamental principles may be illustrated from cases in other jurisdictions.

49. In Camenzind v. Switzerland (App. No. 2135/93) (1999) 28 EHRR 458 at 476 and 477 it was stated:-

“46. In the present case the purpose of the search was to seize an unauthorised cordless telephone that Camenzind was suspected of having used contrary to section 42 of the Federal Act of 1922 regulating telegraph and telephone communications. Admittedly, the authorities already had some evidence of the offence as the radio communications surveillance unit of the Head Office of the PTT had recorded the applicant’s conversation and Camenzind had admitted using the telephone. Nevertheless, the Court accepts that the competent authorities were justified in thinking that the seizure of the corpus delicti - and, consequently, the search - were necessary to provide evidence of the relevant offence.

With regard to the safeguards provided by Swiss law, the Court notes that under the Federal Administrative Criminal Law Act of 22 March 1974, as amended, a search may, subject to exceptions, only be effected under a written warrant issued by a limited number of designated senior public servants and carried out by officials specially trained for the purpose; they each have an obligation to stand down if circumstances exist which could affect their impartiality. Searches can only be carried out in ‘dwellings and other premises … if it is likely that a suspect is in hiding there or if objects or valuables liable to seizure or evidence of the commission of an offence are to be found there’; they cannot be conducted on Sundays, public holidays or at night ‘except in important cases or where there is imminent danger’. At the beginning of a search the investigating official must produce evidence of identity and inform the occupier of the premises of the purpose of the search. That person or, if he is absent, a relative or a member of the household must be asked to attend. In principle, there will also be a public officer present to ensure that ‘[the search] does not deviate from its purpose’. A record of the search is drawn up immediately in the presence of the persons who attended; if they so request, they must be provided with a copy of the search warrant and of the record. Furthermore, searches for documents are subject to special restrictions. In addition, suspects are entitled, whatever the circumstances, to representation; anyone affected by an ‘investigative measure’ who has ‘an interest worthy of protection in having the measure … quashed or varied’ may complain to the Indictment Division of the Federal Court. Lastly, a suspect who is found to have no case to answer may seek compensation for the losses he has sustained.

As regards the manner in which the search was conducted, the Court notes that it was at Camenzind’s request that it was carried out by a single official. It took place in the applicant’s presence after he had been allowed to consult the file on his case and telephone a lawyer. Admittedly, it lasted almost two hours and covered the entire house, but the investigating official did no more than check the telephones and television sets; he did not search in any furniture, examine any documents or seize anything.”

The European Court of Human Rights held at paragraph 47:-

“47. Having regard to the safeguards provided by Swiss legislation and especially to the limited scope of the search, the Court accepts that the interference with the applicant’s right to respect for his home can be considered to have been proportionate to the aim pursued and thus ”necessary in a democratic society” within the meaning of Article 8. Consequently, there has not been a violation of that provision.”

50. In Hunter v. Southam Inc. [1984] 2 S.C.R. 145 at 146 to 147 Dickson J. of the Supreme Court of Canada held:-

“First, for the authorization procedure to be meaningful, it is necessary for the person authorizing the search to be able to assess the conflicting interests of the state and the individual in an entirely neutral and impartial manner. This means that while the person considering the prior authorization need not be a judge, he must nevertheless, at a minimum, be capable of acting judicially. Inter alia, he must not be someone charged with investigative or prosecutorial functions under the relevant statutory scheme. The significant investigatory functions bestowed upon the Restrictive Trade Practices Commission and its members by the Act vitiated a member’s ability to act in a judicial capacity in authorizing a s. 10(3) search and seizure and do not accord with the neutrality and detachment necessary to balance the interests involved.

Second, reasonable and probable grounds, established upon oath, to believe that an offence has been committed and that there is evidence to be found at the place of the search, constitutes the minimum standard consistent with s. 8 of the Charter for authorizing searches and seizures. Subsections 10(1) and 10(3) of the Act do not embody such a requirement. They do not, therefore, measure up to the standard imposed by s.8 of the Charter. The Court will not attempt to save the Act by reading into it the appropriate standards for issuing a warrant. It should not fall to the courts to fill in the details necessary to render legislative lacunae constitutional.

In the result, subss. 10(1) and 10(3) of the Combines Investigation Act are inconsistent with the Charter and of no force or effect because they fail to specify an appropriate standard for the issuance of warrants and designate an improper arbiter to issue them.”

This sets an appropriately high standard for a search warrant process.

51. The Court applies the following principles. For the process in obtaining a search warrant to be meaningful, it is necessary for the person authorising the search to be able to assess the conflicting interests of the State and the individual in an impartial manner. Thus, the person should be independent of the issue and act judicially. Also, there should be reasonable grounds established that an offence has been committed and that there may be evidence to be found at the place of the search.

40. What is left out of the argument on behalf of Kevin Braney against s 30 of the 1939 Act, as to constitutionality and its Convention compliance, is the stark difference between arrest, an ongoing process of investigation where the accused has a lawyer upon request and at all interviews, and the one-off process of search under a warrant. This is a key factual, but also analytical difference. Upon arrest, a suspect, be that suspect the offender in respect of the crime for which the arrest took place or not, and until conviction all are presumed innocent, should be protected by basic rights. These include such legal advice as will distinguish as between the entitlement of the authorities to take sample or to require information or whereby inferences might be drawn through silence or through not mentioning in advance a fact important to a potential defence. Safeguards such as videotaping, presence of a lawyer during interviews, recording interviews, fairness of treatment, consultations, meals and sleep, which are precautions common to both s 30 detention and all other forms of detention set out in the above table, constitute the application of necessary balance after an event. Here the event is an ongoing scrutiny into someone’s mind. In short, the difference between a search executed on the basis of a search warrant and the extension of detention is that a search is a one-off event while detention is an ongoing process with the purpose of investigating an offence. Once the search has been carried out the home has already been entered in an irreversible way. This is not so with an ongoing detention. Thus, a search requires prior scrutiny and care while an arrest demands the application of rights from the time it takes place and up to release. In so far as there is a difference between the procedures for arrest and detention as between s 30 and other forms of arrest and detention for different offences, this is argued by Kevin Braney to infringe Article 40.1 of the Constitution.

41. This argument is untenable. Although all are, as human persons, to “be held equal before the law”, the text continues that this “shall not be held to mean that the State shall not in its enactments have due regard to differences of capacity, physical and moral, and of social function.” Section 30, differentiated from other arrest powers, does not discriminate but rather responds differently. In the case of crimes enabling a s 30 arrest, the police power is a response to a deeply serious threat to society and the integrity of the State. This is not homogeneous with other police powers because crimes are not homogeneous with one another. Some crimes are ones for which there is no search warrant power, some crimes do not carry any power of arrest; the attendance of the offender is secured instead by a court issuing a summons requiring attendance to answer a charge and the court may order arrest if the defendant does not show up, or may proceed in his or her absence if service is properly proven. For some specific crimes there may be a right to take samples, for others there may be none. This is a matter of utility and the careful classification of a crime and of the powers needed to properly investigate it. Thus, road traffic legislation, which may encompass offences which may have consequences from the need to enforce safety on the highways, or which may involve dangerous driving causing death or serious injury, incorporates the requirement to take a breathalyser test, or formerly to give a urine or blood sample, at the option of the suspect, but only where intoxicated or drugged driving is suspected. The powers under s 30 of the 1939 Act broadly extend to what may loosely be called organised crime or terrorist offences, but not to murder. Even though it may be relevant, a murder suspect is not subject to the same constraints as to sampling as a person stopped pursuant to police powers on the road. For safety, random testing on the highways is introduced but that approach may not be applicable to other suspected offences. Stop and search powers apply under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1977 to 2016 but why not to murder suspects? The only answer should the authorities seek to investigate is arrest and this requires considerable preparation so that an investigation consequent on arrest may be worthwhile. While the patchwork quilt of police powers has been standardised to a degree by the passing of general legislation, what this might be generally seen to be illustrative of is a legislative impulse to clear up anomalies. Hence, s 10 of The Criminal Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1997 gives a general power to the District Court to issue a search warrant. Whereas, s 4 of the 1984 Act gives a general power of arrest to citizens and police of arrest but there will be other offences carrying a lesser penalty than 5 years or more where arrest powers exist by virtue of statute. But there are other search powers outside these general powers and there are other arrest and investigation powers as well.

42. The guarantee of equality in the Constitution at Article 40.1 is based on untenable differences in legal status being drawn on a basis of discrimination against human personality, the essence of what defines an individual as human. Obvious discriminations are on the basis of ethnicity, gender, sexuality, political allegiance or faith. But, in addition, the capacity of people may be different, as between those under age and those capable of making more mature decisions, and to strive towards equality, varying treatment may be appropriate; as where limitations for commencing actions on contract or tort differ based on the age litigants are when a wrong occurs to them; O’Brien v Keogh [1972] IR 144. If discrimination is alleged, the first question must revolve around what the discrimination is claimed to be and as regards what other situation or what other treatment of a class of individuals. Always, a comparator is therefore needed; OR v An tÁrd Chláraitheoir In the Matter of s.60(8) of the Civil Registration Act 2004 and in the matter of MR and DR[2014] 3 IR 533, O’Donnell J at paragraph 241. Every case where the law permits detention to be extended beyond 48 hours, and possibly up to 72 hours or 168 hours, requires the intervention of a judge. No instance of detention below 48 hours requires the intervention of a judge. Several other forms of arrest carry detention powers beyond those of s 30 of the 1939 Act. While the limitation as to human personality in decisions as to the constitutionality of discrimination has been treated less rigidly in recent decisions, allowing condemnation of laws which unfairly and without reason target one class of persons over another, where the argument on behalf of Kevin Braney leads is towards a principle of complete homogeneity unless headline reasons enable an obvious differentiation as between classes of administrative measures. This ignores that problems in society come and go, as with the sudden wave of addiction to heroin in Dublin inner city communities in the late 1970s, or the need to suddenly respond to viral pandemics, to the jolting realisation that organised gangs stretch controlling filaments into society that are criminogenic and invidious. There may be a legitimate legislative purpose for differing responses; hence such differing responses are not treating people as unequal before the law as these responses are to situations; Brohoon v Ireland [2011] 2 IR 639.

43. Part of the rationale behind the principle that legislation is presumed to be in conformity with the Constitution must be the adherence to the values of the State whereby public representatives are elected to legislate and to the measure of appreciation that courts should afford to democratic responses in the wider context of public policy or as a legitimate reaction to public emergencies. Hence, while there is a guarantee of the law upholding the equality before the law of humanity, there no absolute guarantee of equality, much less is there a requirement of mathematical uniformity; Quinn’s Supermarket v Attorney General [1972] IR 1. Where, however, an unjustifiable difference that generates a gross inequality emerges, this requires justification on the basis of difference in capacity or on a reasoned basis of social function. To forego a contest on the political offence exemption in some cases, leaving another suspect to be extradited in respect of the same offence, breaches the equality guarantee; McMahon v Leahy [1984] IR 525. As does allowing foreign adoptions on a particular basis in several cases as to the authority of the Mexican High Court but refusing such recognition in other cases; Udarás Úchtála v M & Others [2020] IESC 64 in that instance having a positive effect legitimating adoption in the same context as others.

44. Uniformity is not what Article 40.1 of the Constitution requires; Re Article 26 of the Planning and Development Bill 1999 [2000] 2 IR 321, GAG v Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform [2003] 3 IR 442. As Kelly: The Irish Constitution at [7.2.100] explains:

Equality does not mean uniformity; laws may legitimately differentiate, and in some situations justice requires that they must do so. The courts have several times said that Article 40.1 does not mean that any legislative scheme must present identical features to all citizens; such a mechanical uniformity, in failing to appreciate the existence of categories naturally different (in the senses relevant to the purpose of the legislation) would work inequality in its result, rather than equality.

45. The first and fundamental question is surely whether the arrest power is an impermissible interference with liberty? If it is, then if everyone arrested is treated in the same way that remains wrongful. If it is not, then unless there is a discrimination based on immutable characteristics then the scope for an inequality claim is limited, since otherwise there would be an impossible system where every time a change was made to the law it would render all extant provisions unconstitutional and contrary to the Convention. It has to be possible to develop the law incrementally and by responding to individual situations with different provisions, so long as these do not interfere with impermissibly with a fundamental right under the Constitution and under the Convention. As to extension of detention, several other powers, as the above table demonstrates, depend upon the intervention of a Superintendent to extend detention and then, perhaps at a later stage, a Chief Superintendent. All such powers depend upon reasonable suspicion and upon the reasonableness of any decision to extend the deprivation of liberty which an arrest entails. In arrest, the focus of the legislation is legitimately on a legal requirement that reason replace any supposed ‘trained instinct’ and extension beyond a particular limit depends upon that train of reason being demonstrated to a superior officer and beyond that to a court. Hence, rights begin on arrest and are enforced by legal assistance as a mandatory constitutional requirement. That is different to the invasive quality of a search, ordinarily a shocking intrusion into privacy and one without legal assistance where the analysis requiring compliance with the law is front-loaded to the application and the need to demonstrate before a judge or an independent high-ranking police officer that reasonable grounds exist for suspecting the presence of evidence in the targeted premises or home.

Protection from discrimination under the Convention

46. Thus there is no unlawful discrimination under the Constitution. The only alternative argument advanced was that under the European Convention on Human Rights. According to sparse submissions for Kevin Braney: