Note 1 Pacorini Metal Asia Pte Ltd (Pacorini), later re-named Access World Logistics (Singapore) Pte Ltd (Access World). [Back]

Note 2 Natixis S.A. v Marex [2019] EWHC 2549 at [233]-[238]. [Back]

Note 3 In this case, Access World / Pacorini. This text is quoted in Marex at [229], noting that this is a term of the contractual bailment between the original bailor and Access World). This wording appears on each original, copy and counterfeit warehouse receipt at issue in these proceedings. [Back]

Note 4 Ang Peng Leong Jeremy, CEO of Straits Financial since 2011. CEO of Straits and father of Timothy Ang. [Back]

Note 5 J. Ang, cross-examination, Day 9 p. 14/14-22. [Back]

Note 6 J. Ang 1 §10. [Back]

Note 7 J. Ang §11. [Back]

Note 8 J. Ang §11. [Back]

Note 9 D10’s Re-Amended RFI §1. [Back]

Note 10 Ms Yuzhen Sherraine He, Vice President of Straits since May 2011, and Senior Vice President of Straits (Singapore) Pte Ltd since July 2016. Responsible for managing Straits’ commodities trading team on a day-to-day basis. [Back]

Note 11 J. Ang 1 §21: “once the deal was agreed in principle with Steven Kao, I left it to Sherraine to sort out the details”. [Back]

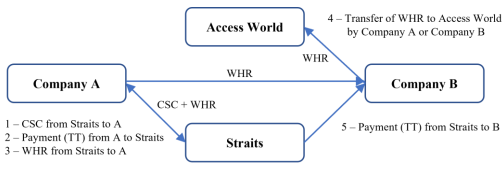

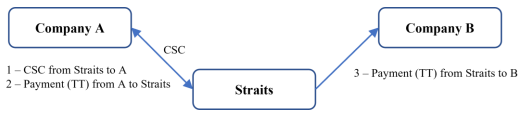

Note 12 Or possibly Company A. [Back]

Note 13 Ms He had said in her first witness statement that the receipt was sent back to Straits: He 1 §21: “In every case of a Type 1 Trade, the original warehouse receipts were delivered to the relevant buyer and re-delivered back to us on the re-purchase side later”. It appears instead from the email from Mr Kao to Ms He dated 4 March 2014 and the email from Jessie Li to Ms He dated 10 March 2014 that the arrangement was that, where Straits was to provide an original warehouse receipt, that WHR would be delivered to Mr Kao’s company in China for onwards transmission to a Pacorini/Access World warehouse in China (for cancellation). [Back]

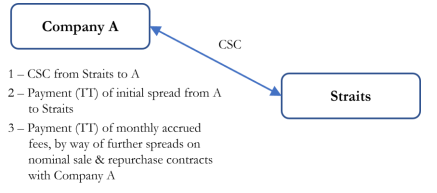

Note 14 Mr Kao to Ms He (with Mr J. Ang and others in copy), 4 March 2014: “With our transactions, there are two types of document requirement on the WHR, Color Scan Copies (CSC) only or CSC with Orignals [sic] to follow…” [Back]

Note 15 Ms He to Mr Kao in the same email chain, 3 March 2014. [Back]

Note 16 See the market experts’ Joint Memo §4.1. [Back]

Note 17 CH & MW Defence, §4(1). [Back]

Note 18 Three were provided by D1 on 14 December 2016, and 6 were provided by D2 on 20 December 2016. [Back]

Note 19 He 1 §180. The metal was sold to avoid it being subject to a freezing order – see further below. [Back]

Note 20 Tan Hui Ying, an executive in the Trade Services team at Straits from 3 March 2014. Senior Executive in the same team from 1 January 2016 and Assistant Vice President from 1 January 2018. [Back]

Note 21 Li Shuyi Lindy, an employee of Straits working in its operations team. [Back]

Note 22 Wu Chong Beng, an employee of Straits working in its operational team. [Back]

Note 23 Radley §24 & §149. [Back]

Note 24 Radley §26 & §150. [Back]

Note 25 At (5) of the Prayer for Relief in the Particulars of Claim. [Back]

Note 26 Particulars of Claim, prayer to relief, paras (1) & (3). See also paras. 544-545 of the Claimant’s closing. [Back]

Note 27 Particulars of Claim §§78-80 (unjust enrichment). [Back]

Note 28 Particulars of Claim §§81-82 (breach of contract). [Back]

Note 29 Particulars of Claim §77A. [Back]

Note 30 An iron ore and steel trader at Puyang and a director and 30% shareholder of Transcendent SG. Son of Jeremy Ang. It was in issue whether Timothy Ang was the beneficial owner of the 30% shareholding in Transcendent SG (see below). [Back]

Note 31 Section 2 DRD questionnaire, dated 22 June 2020. [Back]

Note 32 By Rajah & Tann LLP, not Reed Smith LLP. [Back]

Note 33 See Mr Springer’s email dated 30 November 2014 in which he told Ms He, “Remind that you always maintain title”; Mr Chong’s email to Ms He dated 16 December 2015 stating that “the goods still belong to [Straits]”; and Ms Foo’s email to Ms He dated 2 March 2015 in which Ms Foo emphasised that, for cargoes financed by VAM, Straits would have to ensure that “there is no actual title transfer to counterparty” in order not to breach Straits’ contract with VAM. See too Ms He’s email in which she told Ms Tan, Ms Lindy Li and Mr Wu that “the original never once leave our hands.” [Back]

Note 34 As Lord Diplock explained in Snook v London & West Riding Investments [1967] 2 QB 786 at p. 802, a sham:

“… means acts done or documents executed by the parties to the ‘sham’ which are intended by them to give to third parties or to the court the appearance of creating between the parties legal rights and obligations different from the actual legal rights and obligations (if any) which the parties intend to create”.

And Neuberger J (as he then was) stated in National Westminster Bank v Jones [2001]1 BCLC 98 at paragraph [59]:

"A sham provision or agreement is simply a provision or agreement which the parties do not really intend to be effective, but have merely entered into for the purpose of leading the court or a third party to believe that it is to be effective."

[Back]

Note 35 i.e. Steven Kao (D3). [Back]

Note 36 Although the events of November/December 2014 discussed above do raise concerns about Ms He’s behaviour shortly before the ING episode. [Back]

Note 37 He 1 §119: “Mr Kao and Mr Springer wanted to be able to show third parties that whoever holds the original receipt will be able to take it to the warehouse keeper and take delivery of the underlying cargo.” [Back]

Note 38 Every purported sale to Carlyle (and to later Repo Transaction counterparties) was accompanied by a PMA Letter obtained by Straits from Access World, naming the relevant purchasing entity.

[Back]

Note 39 This paragraph is in red type in the original email [Back]

Note 40 Tan 1 §50; He 1 §§161-164. [Back]

Note 41 Email from Ms Tan to Wu Chong Beng cc’ing Sherraine He and Lindy Li dated 24 April 2015. [Back]

Note 42 In addition to MCM’s ‘Carlyle Transaction Schedule’, see Mr Kao’s witness statement §48 and §54; D3/D4 Reamended Defence §22. [Back]

Note 43 Tan 1 §21. [Back]

Note 44 These were, of course, the fake WHRs. [Back]

Note 45 Vincent Joutain, operations manager for Genesis. [Back]

Note 46 This part of the sentence (“Yes WHR is in the hands of Straits”) is in red type in the original email. [Back]

Note 47 This sentence (“We would not know as the WHR could be sold to other parties from our buyer”) is also in red type in the original email. [Back]

Note 48 Being respectively (i) copies of COO and COA; (ii) confirmation that the metal can be warranted within a reasonable period of time and (iii) a copy of warehouse signature list. [Back]

Note 49 This last sentence (“Straits will no longer have any interest in the materials when we receive full payment from the Buyer”) is in red type in the original email. [Back]

Note 50 The WeChat messages exchanged between Ms He and Mr Kao on 2 September 2016 show that Ms He asked Mr Kao if she could make a personal investment of US$200,000 with Kao in a venture called 13 mile “if you will allow”. [Back]

Note 51 Indeed, Mr Ashton’s summary tables 3.1 ad 3.2 in his first report show that very substantial sums were received by Transcendent companies from MCM (which MCM seeks to trace), including Transcendent SG. [Back]

Note 52 This is, contrary to Straits’ submission, consistent with the way in which MCM pleaded its case – see paragraph 71.6A of the RRRAPOC [Back]

Note 53 Further examples are as follows: the email from Ms He to Mr Kao on 11 December 2015: “I’m talking to another financing party, so just want to be sure that you still have demand for CSC as long as you can do it with VAM on your end”; and WeChat messages between Ms He to Mr Kao on 2 December 2016: “OK so we send 14.5mil csc first to Jessie?”, “We sent the csc over already!”. [Back]

Note 54 Kao §67: “not closely associated with the terms of those trades”; Kao §71 – “I had no reason to believe that the Straits Contracts were anything other than genuine sale and purchase contracts that involved Straits providing original warehouse receipts to CH or MW. (…) It never occurred to me that Straits would not deliver original warehouse receipts to CH/MW.” [Back]

Note 55 He 1 §14; He 2 §§22-23. [Back]

Note 56 Global Display Solutions Limited v NCR Financial Solutions Group Limited [2021] EWHC 1119 (Comm) at [105] per Jacobs J. See Vald. Nielsen Holdings and Ors v Baldorino [2019] EWHC 1926 (Comm) at [130] – [159] per Jacobs J for a more extensive review of recent authorities. [Back]

Note 57 Spencer Bower & Handley, Actionable Misrepresentation (5th ed, 2014) (“Spencer Bower”) at [3.01]-[3.12]. [Back]

Note 58 Spencer Bower at [3.05]. [Back]

Note 59 MCI Worldcom International Inc v Primus Telecommunications plc [2004] 2 All ER (Comm) 833, 844 per Mance LJ (words in square brackets inserted by the editor of Spencer Bower op. cit. at [3.01]). Picken J reviewed the authorities in this context in Marme Inversiones 2007 SL v Natwest Markets Plc [2019] EWHC 366 (Comm) at [115]-[123]. [Back]

Note 60 See Mr Dyke’s witness statement at paragraphs 11-19. [Back]

Note 61 See MCM’s Response to RFI, responding to an RFI served by the third to eighth defendants; and see Mr Kao/Genesis’s denial of the alleged implied representations in para 50 of their Re-Amended Defence. [Back]

Note 62 See Geest plc v Fyffes plc [1999] 1 All ER (Comm) 672, 683 (para (iii)(c)), considered and endorsed by the Court of Appeal in PAG v RBS [2018] 1 WLR 3529 at [128] and [132]. [Back]

Note 63 Leeds City Council v Barclays Bank plc [2021] EWHC 363 (Comm) at [95] and [103], (Cockerill J) which concerned whether it was necessary to demonstrate conscious awareness of the particular alleged representation. [Back]

Note 64 POC §§43-44; D1&2 §63. See too the non-admissions at D3-8 Reamended Defence §61 & D10 Re-re-re-amended Defence §21. [Back]

Note 65 Burrows, Restatement of the English Law of Contract (2nd ed, 2020) at §34(5). [Back]

Note 66 Aerostar Maintenance International Ltd v. Wilson [2010] EWHC 2032 (Ch) at [163] per Morgan J, quoted by Bryan J in Lakatamia Shipping at [125]. Morgan J in turn derived these propositions from OBG Ltd v Allan [2008] 1 AC 1 per Lord Hoffmann at [39]-[44] and per Lord Nicholls at [191]-[193] and [202]. [Back]

Note 67 I would have found them to be proven in any event. [Back]

Note 68 [2000] 2 All ER (Comm) 271, at page 312. [Back]

Note 69 Lakatamia Shipping at [85] per Bryan J {M/115/24}, citing Kuwait Oil Tanker at [111] per Nourse LJ. [Back]

Note 70 ibid, citing Clerk & Lindsell on Torts (23rd ed) at [23.104]. [Back]

Note 71 ibid, citing Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co Ltd v Veitch [1942] AC 435, 479 per Lord Wright. [Back]

Note 72 Kuwait Oil Tanker Co SAK v Al Bader (Moore-Bick J, unreported, 17 December 1998); Erste Group Bank AG v JSC "VMZ Red October" [2013] EWHC 2926 (Comm); [2014] BPIR 81, at [103] (overturned on appeal [2015] EWCA Civ 379; [2015] I.C.L.C. 706, but not on this point). [Back]

Note 73 [2009] EWHC 1276 at [842] onward, in particular [846] and at [948]-[952]. [Back]

Note 74 I add that I would have reached the same conclusions concerning Straits’ involvement in the conspiracy even had I found that Ms He had not deliberately deleted her WeChat messages. [Back]

Note 75 See Meretz Investments v ACP [2007] EWCA Civ 1303; [2008] Ch 244 at [146]; Bank of Tokyo-Mitsibishi v Baskan Gida [2009] EWHC 1276 (Ch) per Briggs J at [826]-[833], and in particular [833]; Digicel v Cable & Wireless [2010] EWHC 774 (Ch) per Morgan J at Annex I [84]. See also Grant & Mumford [2-045]: “Subsequent cases have treated OBG v Allan as authoritative on the mental elements of an unlawful means conspiracy claim”. [Back]

Note 76 Note that in Kuwait Oil Tanker (CA, 2000) [121], Nourse LJ approved the following dictum of Oliver LJ in Bourgoin SA v. Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food [1986] QB 716 at 777: “If an act is done deliberately and with knowledge of the consequences, I do not think that the actor can sensibly say that he did not ‘intend’ the consequences or that the act was not ‘aimed’ at the person who, it is known, will suffer them.” At first sight this may seem difficult to reconcile with the observations of Lord Hoffmann and Lord Nicholls in OBG but Grant & Mumford suggest that this dicta must now be read in light of the principles set out in OBG and therefore the Kuwait Oil case is “probably best understood as an example of “the obverse side of the coin analysis” [2-043]. I agree. [Back]

Note 77 [1990] 1 QB 391. [Back]

Note 78 [1982] AC 173. Lonhro owned and operated an oil pipeline running from Mozambique to Southern Rhodesia. On November 11, 1965, Rhodesia declared independence unilaterally. On December 17, the Southern Rhodesia (Petroleum) Order 1965 made it a criminal offence to supply oil to Rhodesia without licence from the Minister of Power, and no further oil was tendered through the pipeline. B.P. and Shell continued, however, to supply Rhodesia through other means. Lonrho claimed damages against them on the grounds that their actions had brought about, and prolonged, the unilateral declaration of independence, and the consequent disuse of their pipeline. The Court of Appeal held that Lonrho had no cause of action. The House of Lords held, dismissing the appeal, that the civil tort of conspiracy only arose where there was an agreement for the purpose of injuring the claimant’s interests, not for the prosecution of the defendant’s interests, even if the agreement constituted a criminal offence. [Back]

Note 79 Lonhro Plc v Fayed (No. 1) [1992] 1 AC 448 at 468 E-G. [Back]

Note 80 The suggestion to the contrary in Grant & Mumford at paragraphs [2-045] and [2-086] (“The House of Lords in the later decision in Total Network reintroduced the concept of action “targeted” at or “directed” against the claimant”), which was cited by Straits, I consider to be wrong. Likewise, the test of targeting the claimant was not re-introduced by the court in JSC BTA Bank v Ablyazov [2018] UKSC 19, as suggested by Grant & Mumford at [13]-[14], which suggestion was also adopted by Straits. [Back]

Note 81 [2012] EWHC 3680 (Ch) [Back]

Note 82 [1983] 1 SCR 452. [Back]

Note 83 With respect to (1) above, this approximates to Category 1 intention as outlined inOBG. This is uncontroversial. However, with respect to (2) (“constructive intent”), Etsey J’s formulation falls outside the categories of intention as articulated by Lords Hoffmann and Nicholls in OBG. That the defendant “should know” that “injury to the plaintiff is likely to […] result” falls somewhere between Categories 3 and 4 formulated in OBG in so far as it more than a “merely foreseeable consequence” (given it is “likely”) (Category 3) but by no means the obverse side of the coin of the defendant’s actions (Category 4). [Back]

Note 84 [2-122]. [Back]

Note 85 [2-124]. See also Kuwait Oil [133]; The Dolphina [2012] Llyod’s Rep 304 (High Court of Singapore) at [282]: “A conspirator need not know all the details of the plot as long as he is aware of the common objective and what his role in bringing it about involves.” [Back]

Note 86 [2-125]. [Back]

Note 87 [2-126]. [Back]

Note 88 Straits’ Closing, para. 39. [Back]

Note 89 Straits’ Closing, [46] and MCM’s Closing, [431]. [Back]

Note 90 Straits’ Written Opening at [35]. [Back]

Note 91 [Annex I, 71]. [Back]

Note 92 [11]-[15]. [Back]

Note 93 [95]. [Back]

Note 94 [116] and [119] in particular. [Back]

Note 95 Straits’ Closing, [44]. [Back]

Note 96 There is a requirement in the first element of the tort (‘combination/agreement’) that the defendant be “sufficiently aware of the surrounding circumstances and share the same object [with the other conspirators] for it properly to be said that they were acting in concert at the time of the acts complained of”. [Back]

Note 97 [2021] Ch 233 at [154]. [Back]

Note 98 Claimant’s Closing [410]. [Back]

Note 99 Smith New Court Securities Ltd v Citibank NA [1997] AC 254 at 266H-267D. [Back]

Note 100 MCM entered into a Commodities Sale and Purchase Master Agreement with Come Harvest on 29 April 2016, with Mega Wealth on 13 June 2016 and with Genesis on 13 June 2016. [Back]

Note 101 Mr Riley’s witness statement [31]. [Back]

Note 102 The relationship between MCM and ANZ was governed by a Commodities Sale and Purchase Master Agreement dated 8 December 2015. The contract used for individual transactions was appended to this Master Agreement. [Back]

Note 103 MCM’s right to repurchase is set out at clause 6 of the Master Commodities Purchase Agreement between ANZ Commodity Trading PTY LTD, ANZ Banking Group Limited and MCM dated 8 December 2015. [Back]

Note 104 Mr Riley’s witness statement [33]. [Back]

Note 105 Under the Commodities Sale and Purchase Master Agreement with ANZ, title to the metal only passed to ANZ once it had paid MCM for the metal (see clause 4.3(1) of Master Agreement between MCM and CH dated 29 April 2016). Similarly, under the Commodities Sale and Purchase Master Agreement with Come Harvest and Mega Wealth title to the metal only passed on payment (see clause 7(a) of the same agreement): “Once ANZ were in possession of the WHRs, I understood that they would satisfy themselves that the WHRs were in order before releasing funds to MCM via SWIFT transfer. MCM would then release the relevant funds to the bank account of the customers.” (Mr Riley witness statement [40]); “Once ANZ were in possession of the hard copy WHRs for the transaction and a signed confirmation with MCM, ANZ would make payment to MCM. Once the funds had been received by MCM, MCM would then make payment to the bank account of CH or MW.” (Mr Dyke witness statement [19]).

[Back]

Note 106 British Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co Ltd v Underground Electric Railways Co of London Ltd [1912] AC 673. [Back]

Note 107 In so doing the HL strongly approved the Court of Appeal’s decision in Rodocanachi v Milburn (1886) 18 QBD 67 (CA) where the contract that was breached was not one of sale but of carriage of goods, the non-delivery resulting from the goods being lost at sea in the course of carriage. The price at which the charterer had sold the goods in advance of the breach of contract, a price lower than that at the time of due delivery, was not allowed to reduce the damages. [Back]

Note 108 To like effect, see also R&W Paul v National Steamship Co (1937) 56 Lloyd’s LLR 28 at 33:1 per Goddard J. [Back]

Note 109 [470 at col. 2]. [Back]

Note 110 [33]. [Back]

Note 111 Transcript Day 14/44/17-45/2. [Back]

Note 112 In its oral closings, Straits accepted that OMV Petrom stands for the proposition that “when assessing damages in deceit one does not look at anything after the point of breach” [Transcript Day 16 pp. 127/3-11.]. [Back]

Note 113 Transcript Day 16 p. 129/7-22. [Back]

Note 114 Transcript Day 16 p. 129/7-22. [Back]

Note 115 21st edition [9-004-9-006]. [Back]

Note 116 The first and third rules were endorsed by the Supreme Court in Sainsbury’s Supermarkets Ltd v Visa Europe Services LLC and others; Sainsbury’s Supermarkets Ltd v Mastercard Incorporated and others [2020] UKSC 24 at [212], [214]. The three rules as a whole were also endorsed by Leggatt J in Thai Airways International Public Co Ltd v KI Holdings Co Ltd [2015] EWHC 1250 (Comm) [33]. [Back]

Note 117 21st edition, [9-111]. [Back]

Note 118 Lowick Rose LLP v Swynson Limited & another [2017] UKSC 32, [2018] AC 313, [13]. [Back]

Note 119 [2017] UKSC 32, [2017] 2 WLR 1161 [11]. [Back]

Note 120 Transcript Day 16/130/6-141/25. [Back]

Note 121 "The general rule is that loss which has been avoided is not recoverable as damages, although expense reasonably incurred in avoiding it may be recoverable as costs of mitigation. To this there is an exception for collateral payments (res inter alios acta), which the law treats as not making good the claimant's loss." [11]. [Back]

Note 122 “The critical factor is not the source of the benefit in a third party but its character. Collateral benefits are those whose receipt arose independently of the circumstances giving rise to the loss. Thus, a gift received by the C, even if occasioned by his loss, is regarded as independent of the loss because its gratuitous character means that there is no causal relationship between them”. [11]. [Back]

Note 123 The editors of McGregor (21st edn.) accurately summarise the decision as follows [9-142]: “Charterers repudiated a charterparty. The owners accepted the repudiation but had difficulty in obtaining a new charter. So, in October 2007, they sold the ship for US $23,765,000 and claimed from the charterers in breach the loss of profits from the charter, amounting to around €7,500,000. By the time of hearing in November 2009, the value of the ship had fallen to $7,000,000. The charterers claimed that the owners were required to bring into account the large benefit from early sale of the ship. This would have meant that the owners reaped a large profit and suffered no loss caused by the breach. It had been found as a “clear” fact by the arbitrator that but for the breach the owners would not have sold the vessel. In other words, it was found that the profit made was caused by the breach. Nevertheless, in the decision of the Supreme Court, given by Lord Clarke, it was held that the profit on the sale did not need to be brought into account by the owners. Lord Clarke described the result in the language of “legal” causation. By this, he meant that the decision to sell the vessel was an independent commercial decision taken by the owners at their own risk. It was not a reasonably necessary response to the breach. As the Supreme Court later explained, the lost profits from the charterparty could be recovered “without having regard to the overall profitability of the claimant”. [Back]

Note 124 21st edition [9-135]. [Back]

Note 125 Vale SA v Steinmetz [2021] EWCA Civ 1087 at §16 per Males LJ; Global Currency Exchange Network Ltd v Osage 1 Ltd [2019] 1 WLR 5865, [2019] EWHC 1375 (Comm) at §40 per Andrew Henshaw QC; National Crime Agency v Robb [2015] Ch 520, [2014] EWHC 4384 (Ch) at §44 per Sir Terence Etherton C; Bristol & West Building Society v Mothew [1998] Ch 1 at 22F per Millett LJ; Lewis v Averay [1972] 1 QB 198 at 207B-C per Lord Denning MR;Lewin on Trusts, 20th Ed., §8-030;McGrath, Commercial Fraud in Civil Practice, §6.235. [Back]

Note 126 See Vale v Steinmetz [2020] EWHC 3501 (Comm): “The fact that the JVA was voidable on the ground of fraud vitiating Vale’s consent created, as the case-law has described it , an equity (a “rescission equity”) affecting the Initial Consideration payment, such that upon rescission it became impressed with a constructive trust (a rescission trust) […] the rescission equity may affect further or different assets that the asset(s) originally transferred under the voidable transaction, subject to tracing rules.” [Back]

Note 127 See MCM’s skeleton at §48, and Straits’ skeleton at §168 (differently worded but to the same effect). [Back]

Note 128 This passage in Williams was recently relied upon by the Court of Appeal in Byers v The Saudi National Bank [2022] EWCA Civ 43 at [51]. [Back]

Note 129 MCM Closings, [467(4)]. [Back]

Note 130 MCM Closings, [510]. [Back]

Note 131 Claimant’s skeleton, para. 56(i). [Back]

Note 132 I note, in passing, that certain commentators have queried whether this line of authority is challenged by the decision of the Privy Council in Re Goldcorps [1994] UKPC 3 but neither party sought to suggest to me that it is not good law. [Back]

Note 133 MCM’s Closings, [514]. [Back]

Note 134 Lonrho v Fayed No. 2 [1992] 1 WLR 1, 11F-12C per Millett J; El Ajou v Dollar Land Holdings plc [1993] 3 All ER 717 (Millett J); Bristol & West Building Society v Mothew [1998] Ch 1, 22G-23E; Box v Barclays [1998] Lloyd’s Rep Bank 195 at [200]-[201]; Shalson v Russo [2003] EWHC 1637 (Ch) 281 at [108]-[111]; Armstrong v Winnington [2012] EWHC 10 (Ch), [2013] Ch 156 at [125]; National Crime Agency v Robb [2014] EWHC 4384 (Ch), [2015] Ch 520 at [43]-[44]; Re D&D Wines [2016] UKSC 47, [2016] 1 WLR 3179 at [28]; and Vale v Steinmetz [2021] EWCA Civ 1087. [Back]

Note 135 Facts: In a dispute arising out of Al-Fayed's (AF) acquisition of House of Fraser (HF), Lonhro (L) claimed that the contract of sale of part of the share capital in HF to AF should be rescinded. L was aggrieved by the fact that it was bound by an undertaking given to the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry not to acquire more than a 30% shareholding in HF, at the time that AF made a bid for the remaining shares in HF. L claimed had it known that AF would make such a bid, it would not have sold to AF. L alleged AF was aware of this and deliberately deceived L into believing the contrary. [Back]

Note 136 Zogg advocates an original alternative approach to this dilemma at pp. 184-186 of Proprietary Consequences in Defective Transfers of Ownership (2020). [Back]

Note 137 Closing submissions [544]-[545]. Cf. also paragraph (2) of the Prayer of the Re-Re-Re Amended Particulars of Claim. [Back]

Note 138 When further broken down, the issues for determination which were identified by the parties are as follows: “[T]here are 3 broad questions arising on quantum: 313.1. Should the Genesis payments to Straits, or any of them, be included? 313.2. Whether the approach in Ashton-1 or Ashton-2 is the starting point to identify the maximum traceable sum? 313.3. Whether the traceable proceeds of the payments by CH/MW should be reduced by reference to Ms Tan’s evidence?” (Straits’ Closing submissions at [313] and agreed by MCM cf. transcript, Day 15 pp. 77-78). However, MCM then correctly noted (Transcript Day 15 pp. 80-81) that 313.1 and 313.3 are essentially the same issue (whether Straits is a bona fide purchaser for value without notice) and so it makes sense to take the two questions together, as I do below (hence “Tracing Evidence Issue” below refers to question 313.2, while the “Bona Fide Purchaser Issue” refers to both questions 313.1 and 313.3). [Back]

Note 139 Mr Lewis QC stated in oral argument that: “If your Lordship decides the three issues of principle here […] then the parties will probably be able to agree the figure” (Transcript, Day 15, p. 76). [Back]

Note 140 Cf. para, 2.28 of Ashton-1: “By way of example, where an amount is received into an account and the same, or very similar, amount is transferred out of the account on the same day or soon after, I have assumed that the transfer out was fully funded by the money received. This contrasts with the general assumption where, if there were a mix of relevant MCM monies and non-relevant monies in the account before the cited transfer in, the transfer out would be assumed to be funded from any brought forward non-relevant monies first.” And at [2.29] of Ashton-1: “The matching criteria I have used for this exercise, and which I consider to be reasonable, are that for there to be a match (1) the payments must occur within five business days of each other and (2) the difference between the inflow(s) and outflow(s) must be less than or equal to 0.1%. In situations where the matching outflow(s) may slightly exceed the inflow, then the excess difference is allocated based on LIBM.” [Back]

Note 141 Transcript Day 13 p. 34/7-11. [Back]

Note 142 Straits’ Closing [325]. [Back]

Note 143 [30-051]. [Back]

Note 144 Snell’s Equity [30-056]. [Back]

Note 145 See Grant & Mumford, Civil Fraud, ibid, §23-019, Snell’s Equity, §30-058 – 30-061. [Back]

Note 146 Snell’s Equity [30-057]. [Back]

Note 147 El Ajou v DLH Plc [1993] 3 All E.R. 717 at 735–736, per Millett J. Cf. Re Tilley’s WT [1967] 1 Ch. 1179 at 1183: “If a trustee mixes trust assets with his own, the onus is on the trustee to distinguish the separate assets, and to the extent that he fails to do so, they belong to the trust.” (per Ungoed-Thomas J). [Back]

Note 148 (1879) 13 Ch D 696 at 727. [Back]

Note 149 [1903] Ch 356 at 360. [Back]

Note 150 [6.49], The Federation Press, 2021. [Back]

Note 151 Campbell J in Re French Caledonia Travel Service Pty Ltd (in liq) (2003) 59 NSWLR 361 at 386 [83]. [Back]

Note 152 MCM Closing [536]. [Back]

Note 153 MCM Closing [537]. [Back]

Note 154 It appears that the funds in Come Harvest’s, Mega Wealth’s and Genesis’s accounts have been almost entirely dissipated. As of January 2017, there remained only US$26,431.50 in Come Harvest’s account, US$8,379.43 in Mega Wealth’s account and US$78,265.38 in Genesis’s account. There is therefore likely now to be little or nothing left. [Back]

Note 155 Straits’ Closing [320.2-320.3]. [Back]

Note 156 Straits’ Closing [footnote 1002]. [Back]

Note 157 Cf. also [727-8] and [743]. [Back]

Note 158 [735]. [Back]

Note 159 [737]. [Back]

Note 160 See [1193E]. [Back]

Note 161 [102]. InTurner, the Court had to decide whether a beneficiary could choose to take a share in an asset (a house) that had been acquired by the trustee and had increased in value, in circumstances where the trustee “maintain[ed] in her account an amount equal to the remaining fund.” [Back]

Note 162 Cf. Tables 3.3 and 3.6 of Ashton-1. [Back]

Note 163 The agreed dramatis personae notes that Genesis Rover is “A company which was registered at 155 Bovet Road, suite 700, San Mateo CA 94402. It was incorporated on 17 March 2015 and dissolved on 31 January 2017. Mr Kao was its registered agent. D3-D8 do not admit this.” [Back]

Note 164 Cf. Table 3.3. of Ashton-1. [Back]

Note 165 Straits’ Closing [319]. [Back]

Note 166 Straits identified three payments made on 28 June 2016, 5 July 2016 and 19 July 2016. [Back]

Note 167 Straits identified one payment made on 27 June 2016. [Back]

Note 168 Claimant’s Closing [326]. [Back]

Note 169 Claimant’s Closing [329]. [Back]

Note 170 Claimant’s Closing [327]. [Back]

Note 171 [2015] UKPC 13, [2015] 1 WLR 4265 at [33]. [Back]

Note 172 [13]. [Back]

Note 173 [18] per Lord Sumption. [Back]

Note 174 [Transcript Day p. 17/60ff]. .I.e. Claimant’s submission in oral Closings that “Straits knows that if they are getting money from any of CH or MW or Genesis they know and Ms He knows that there was a serious possibility that the money could be the proceeds of fraud” [Transcript Day 15 p. 93/3]. [Back]

Note 175 Claimant’s Closing [475(3)]. [Back]

Note 176 Claimant’s Closing [480]. [Back]

Note 177 [Transcript Day 17 p. 63]. [Back]

Note 178 [Transcript p. 17/63]. [Back]

Note 179 [Transcript p. 17/63-64]. [Back]

Note 180 [Transcript Day 15 p. 83/17]. [Back]

Note 181 Or, I add, a defendant to an equitable proprietary claim. [Back]

Note 182 [526]. [Back]

Note 183 Response 21 at D3 and D4’s Response to the Claimant’s Request for Further Information of the Amended Defence. [Back]

Note 184 Response 22.2 at D3 and D4’s Response to the Claimant’s Request for Further Information of the Amended Defence. [Back]

Note 185 Mr Robb’s additional written submissions, [18]. [Back]

Note 186 Papadimitriou [14-15]. [Back]

Note 187 Grant & Mumford, Civil Fraud, at 23-029. [Back]

Note 188 Lewin, at 44-124. [Back]

Note 189 [1981] AC 513 at 528. [Back]

Note 190 See in this respect Re Gerald Martin Smith Serious Fraud Office and another v Litigation Capital Ltd and others; Serious Fraud Office and another v Litigation Capital Ltd and others [2021] EWHC 1272 (Foxton J). [Back]

Note 191 Re Gerald Martin Smith Serious Fraud Office and another v Litigation Capital Ltd and others; Serious Fraud Office and another v Litigation Capital Ltd and others [2021] EWHC 1272 (Comm), [151]. [Back]

Note 192 [1998] 1 WLR 1, 8 [150]. [Back]